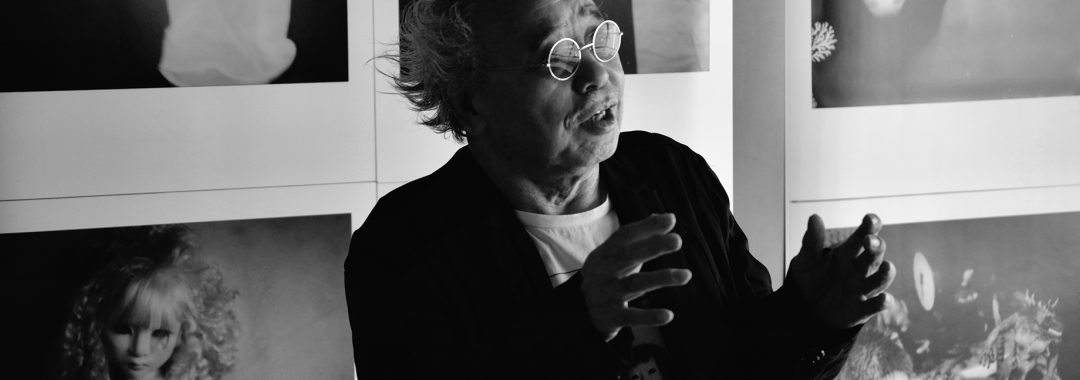

Photo in perex – Nobuyoshi Araki by © Alzbeta Kossuthova.

I am very grateful to Ms. Hisako Motoo of “Art Space AM” for making the realization of this interview possible. Also, I would like to thank Nozomi Takahashi, Keiko Ogura and Atsushi Kubota for their support and help in compiling the interview article. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to you.

Author’s note:

Memories of my dad with a camera in his hands ever since I was small are the first ones connected to photography. He also presented me with a book about black and white photography. Later I got my first camera and started dreaming.

As a lover of black and white photography, I came across the works of many, among which the name Nobuyoshi Araki resonated with me the most. Dreaming the impossible and thinking how great it would be to meet him someday.

Next, I find myself studying the Japanese language and going to Japan.

Here I am in Tokyo now, having met my hero. Getting the chance to get to know him better by talking to him face to face was unbelievable.

Dreams are never too big, nor too impossible.

In your work, you have captured the death of your closest people – father, mother, wife Yoko and your closest cat Chiro – and they became subjects of your photography. Your exhibition “Umegaoka elegy (2019),” reflects mainly you and the everyday things surrounding you in a place, where you live. Can this be considered as focusing on yourself, as a subject of your work, and the inevitable approach of death?

Araki: Why not. Photographing is just a record of living. So, why did it (the latest work) become like this? My most beloved ones – my mother, Chiro, and my wife – they all passed away.

So, after all, the only way to prove that I am alive now is to take photographs of daily life and the place I’m living in. I am not interested in visiting somewhere for shooting. I focus only on myself.

Alzbeta: Right. You are focusing on photographing yourself.

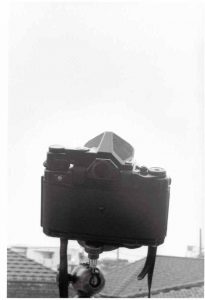

Araki: I became more passionate about documenting and focusing on myself only. Before I was going to photograph objects, but now all photographs I shoot are self-portraits. I feel like the camera is like my additional hand. Gods of Japanese Buddhism, like Ashura, have the third eye. In my case, saying in a very worldly-minded way though, I shoot it with a camera, feeling like it is my third hand instead. Then focusing on myself came spontaneously. Everybody is taking selfies nowadays, I did it much earlier. Haha.

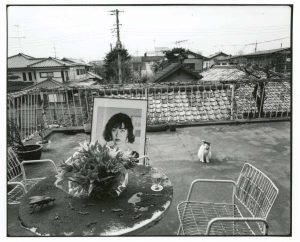

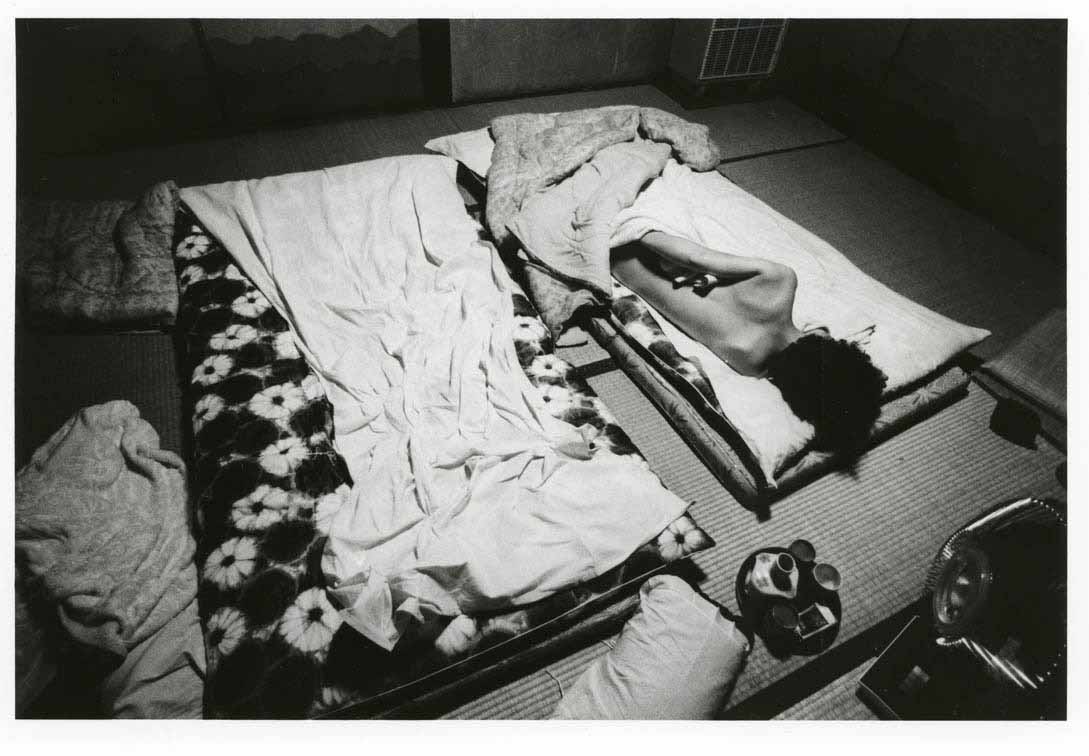

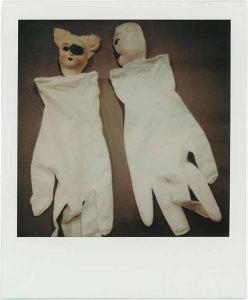

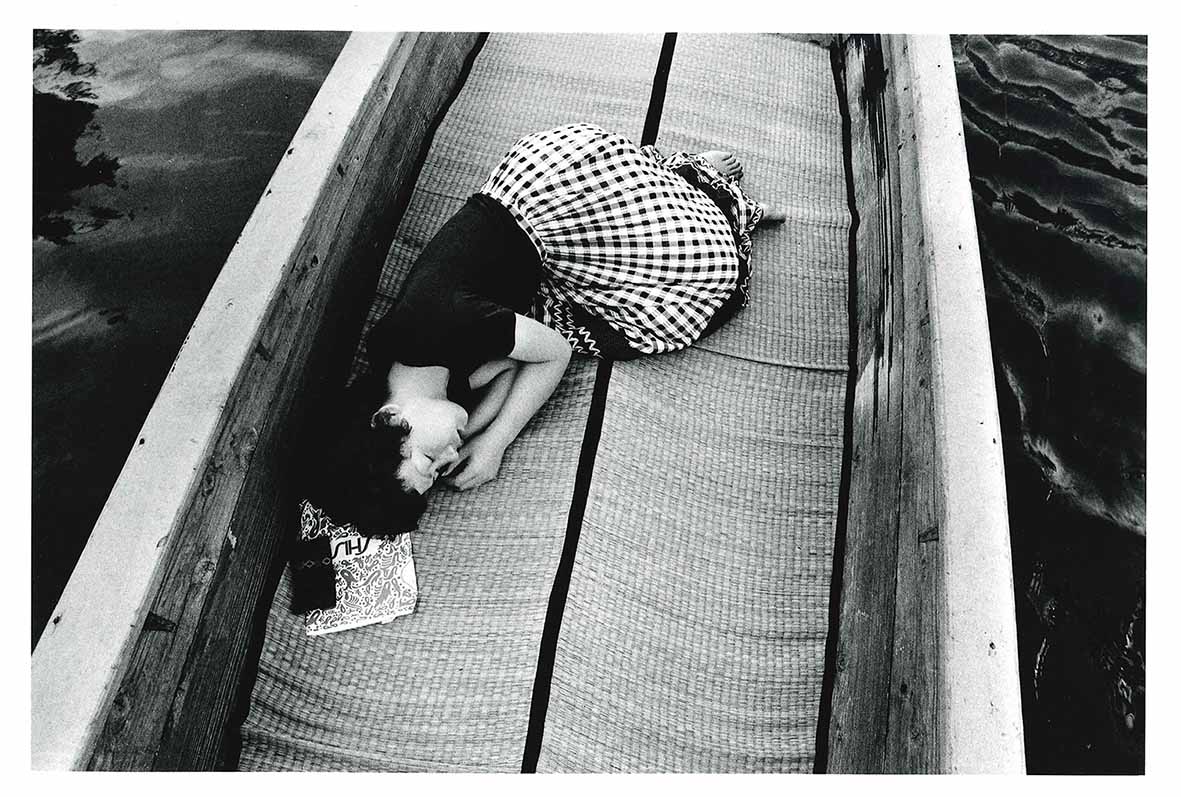

Series: Sentimental Journey / Winter Journey. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

The title “Umekaoga elegy.” The word elegy (reading: BoJō) consists of 2 kanji characters and instead of the first character, that should be standing for “pine for, yearn for,” you used one, that has the same reading [bo], but stands for “grave, tomb.” What are you referring to? Is the grave symbolizing the loss of motivation? Or the end of your career?

Araki: I think the place where I live now is a cemetery rather than the end of life. All places around me, the balcony of my house, etc., actually are a graveyard to me. I feel that I am currently living in a tomb. Even though I’ll give away the title of the next exhibition, I now think of it as the “Jōdo (Amitabha’s Pure Land or (Buddhist paradise)” or “Gokuraku Jōdo (The land of Perfect Bliss).” Umegaoka town, the place where I live now, is the paradise. I take so many photographs in the area that is close to me, because I think of it as “Jōdo.” The surroundings are changing steadily: new houses were built in vacant lots; many residential houses are rebuilt in the neighbourhood, for example, in Gōtokuji town where I used to live also.

I think the place where my life is going on is the paradise maybe. Therefore I think the title of the next exhibition or publication includes the word “Jōdo.” I stroll to take photographs of my neighbourhood, it is a very ordinary town, but I feel it is like “Jōdo.”

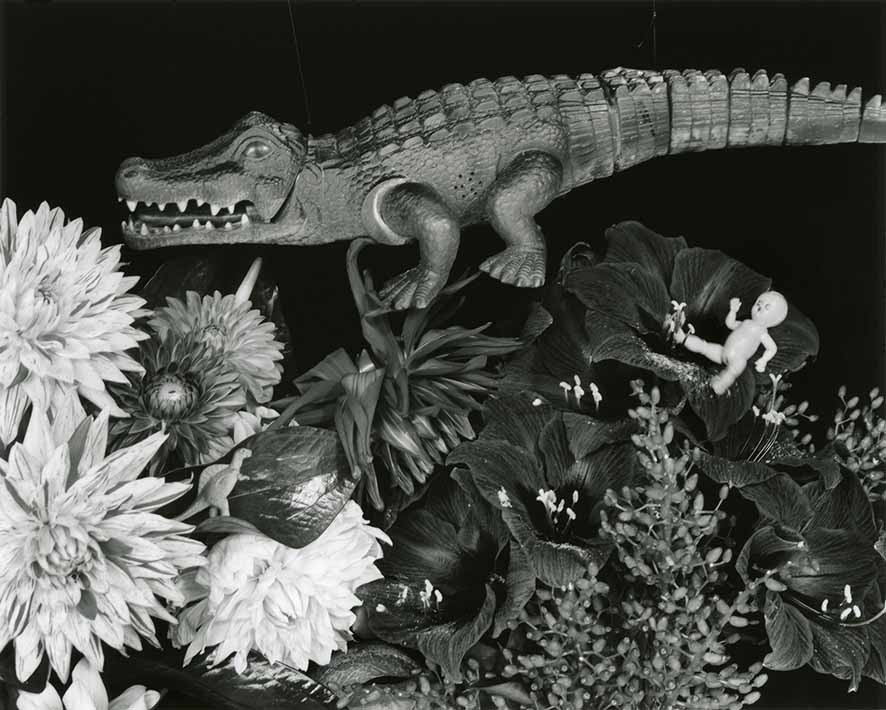

For many years “flowers” have been my subjects. These years I install monsters, figures and dolls playing in a flower garden paradise. I call the series “Kai-Rakuen (mysterious paradise).” “Kai,” a Chinese character, which is also used in a word for “monster (KaiJū)” or “ghost (YōKai).”

Series: Kairakuen. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

Araki: My whole neighbourhood, like the usual streets, is everything, and the range is going to get even smaller. Following this trend, I became to think of the framing of photographs as a coffin. That’s why I say I have only 3 days left in my life. At the moment, I am taking photographs, feeling as if the angle of view through the camera was a coffin.

I’ve been doing it all the time, but lately, everything is great, everything is fascinating – for example, the scenery I see from the window of a taxi, even the corner of the street I stumbled upon while taking a walk, even people on the street, even a child riding a bicycle – I’m getting to a mental state that everyone’s alive, that everything is great. Therefore, I am in a situation, where death and the coffin are close.

I continue to take photographs as if it were my heart pounding, therefore photographing is my heartbeat and I feel like breathing. That is the situation right now. The point is, I try not to reach the top. My top would be my death. Even though, the Grim Reaper always follows me. Goddesses used to be with me before… but, today, a goddess is with me. Haha.

It’s getting better and better. When the element of death deepens, the photographs get better. If I continue to be drawn to photography in this way, I will try not to go to the top; and if it is Mount Fuji, I will make it only to about the 8th station (*note: the closest to the summit of Mount Fuji) and see the sunrise from there. Not reaching the peak – that’s my situation at the moment.

Therefore, I do not care about any camera or any time, I think everyone and everything is great. If you look at the pictures, you find it’s like that, right?

It can be said, that by publishing the nudes of your wife, you were sharing her with the audience. Didn’t you mind it? Or was it, on the other hand, the expression of your closeness and openness with the public?

Araki: It is I who wants to see the photographs I took, not for showing them to the public. So it’s not about creating a work of art or showing it. I am just doing what I like. Photography is something I initially like, even before pushing the shutter.

There was a time when I made scrapbooks (photobooks) out of the photographs I took using sketchbooks from an art supply shop, which were put together into one book and published recently (*note: The book “Gekkō Shashin” was published in November 2019). I photographed anything back then as well.

I asked my friend’s mother to become my photographic model because she was fantastic. I took pictures of people at department stores, a nice guy of a greengrocer in a town, and so many more. Then I made my own layout of photos (in the sketchbooks)…, there was a time like that. At that time I was doing all sorts of things in regards to photography. Although it may be too much to say that I took photos to show them to myself, my point was always if I myself wanted to see them. Such scientific experiments with photography and the relation (I had) with people won’t turn into money, do they?

Let’s say if you work at an advertising company like Dentsu (*note: Dentsu is currently the fifth largest advertising agency network in the world in terms of worldwide revenues), there is a lot of fiction and made-up things. In my case, for example, because I was thought to be good at taking photographs of children and families, I was assigned to advertisements of life insurance companies. In creating an advertisement, strangers were gathered together in the way that the role of the father was this man, the role of the mother was this woman and the role of the children were these kids. I took good photographs of fake families like that. With the piling of these photoshoots, I came to touch with all various techniques related to photography.

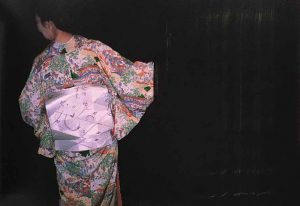

Beyond that, photography is “me.” Unlike unveiling something to society or doing something for society, but rather as expressing my own thoughts and words, “I-photography (ShiShashin – “shi” stands for I and “shashin” for photograph),” my usual pun (from “I-novel (ShiShōsetsu)” which depicts the author’s own life). Photographing things about “me” or something like that, started on our honeymoon. What I did then wasn’t about my wife’s nakedness or such, but it was inevitable, and being naked and something sexy was natural and normal. In short, isn’t it the same as having her clothes on? Even with no clothes, it was one way of her expression. I don’t care that much because those are feelings coming out (from her) and towards the partner. At that time, it became the topic through journals.

Series: Sentimental Journey. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

Alzbeta: So it (making it public) did not come from you.

Araki: Exactly. It did not come from me.

When I met Cornell Capa, the younger brother of Robert Capa, he said Robert was overly honest. At the time I was thinking I had to directly express my feelings. Anyway, I couldn’t stop expressing what I thought honestly. I did not use my wife as my subject to express love. It’s just when I think something is lovely, it’s lovely to me; when I think something is unpleasant, it’s unpleasant to me. I continue to take photographs like that – even now it is still the same. Still being honest.

Alzbeta: That is important.

Araki: Some people say I am naively honest. They say my photographs are “too honest,” or “he is exposing everything and revealing his emotions too much.” However, when Robert Frank, who likes it (my honesty), came, he brought a figurine he made himself as a present for me – even though I was not sure if it was a dog or a cat. I was very happy and proud of that.

While he was here, there was a baseball player called Araki (Araki Daisuke) whose uniform number was 11. When the player was shown on the TV, Frank took photographs of the screen. Later he gave me the print with his writing: “Araki number one!”

Last year I dedicated the book named “Gekkō Shashin” to Robert Frank (he died in 2019). The title comes from the sketchbooks of “Gekkō-sō (*note: art store established in 1917),” even though photos were not taken with the light of the moon (“gekkō” means “moonlight” in Japanese). The titles are not very accurate like that.

I’m playing, after all, with something. I don’t know if it’s true humour or not, but I feel like living is as playing. I was told (by a doctor) to sleep today, but I can’t help but being talkative when I meet a beautiful woman. Haha.

Series: Gekko Shashin. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

You are famous for never repeating yourself. Equally famous for trying new techniques, searching for new topics and their adaptations. Is there something you have always wanted to try, but until now you have never had a chance to?

Araki: I did so many trials, because I leave myself to the “moment.” You don’t know what is going to happen afterwards. I mean, I go along with what happens then, or I am something like a servant of time, so I don’t think photography is something I create or build. Anyway, because I feel like reproducing what happened to me or what I feel every moment, I have never been creative.

The creation comes from models or objects and I am copying what was already created. Usually, painters say what style their work is, right? In photographing, time is always changing and flowing, which can not be any style. Everything changes. Since the core does not change, any change is good. In my case, approaches and methods are all different, right? Taken at that time, in the mood of that time. Only by following what somebody else decides, I don’t want to create anything at all.

Existences, flow of times… everything is interesting and exciting. Things that fluctuate (change) are good anyway; whether they are good or bad actually, anything is good. Changing makes me feel vital. I feel like photographing it or going along with it, so I do not need any specific situation to shoot. I am happy to watch the photographs and feel that’s good. I’m unmanageable. I do not stop praising myself, do I? Haha.

Kinbaku (Shibari) is the ancient Japanese art of bondage tying. What inspired you? Was it only about the visual side of it, or was it more about the feeling of dominance and control, or knowing that the model fully trusts you?

Araki: I don’t have the desire to photograph bondage at any cost. Sometimes when someone happens to ask me to try to shoot photographs of something like that, I accept the challenge. I am up for anything I have never met with and never done before. Having done that, there is something fascinating, something I learn from, and something I realize.

Tying up is not about restraining the person tied up, but its other aspects or something. This is an act, which does not reach any point of “love” though; it brings out a mysterious part of a woman. This is not to abuse, but to bring out hidden areas, some instinct or physiology or something like this in the person.

These years I photograph dolls a lot. They are just dolls, but I feel I could connect with them in some way, be interested in shooting and learn a lot from them. And then, cutting their craniums or one foot off and paint them red for photography, I feel submerged. Sometimes I find such taste might lie already within me. It’s like committing a crime every day or getting into mischief of a kid.

Series: Hanajinsei. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

Araki: I can’t see with this (right) eye, but I feel like I am skipping over it by joking. Let’s say “Love on the Left Eye.” I can play with my unhappiness like this in the photographs. I have spent time like this, just taking it easy, not like pursuing something or seeking the truth, although psychologically and instinctively I might want to know something.

I don’t care, as long as it’s interesting. That’s why I have not been in a slump. I sometimes feel I have done enough already, but I expect more and more things to happen from now on. I mean, I expect I will encounter more and more interesting things. That said, I sometimes also feel miserable, when I see Ryuichi Sakamoto’s (Oscar-winning Japanese composer, who survived cancer of the larynx) comments about his cancer on the TV screen, worrying that something is wrong with my throat, so I may have pharyngeal cancer. Nobody knows who decides it, but it will be as it will be.

“Being alive” means meeting something or someone among various things at every moment, and that is why I hardly deny anything. There, both some happiness and some unhappiness are hiding in it. Even disaster is not just about sadness. I can say so; maybe I only see it through the TV. If it actually happened, that would be very serious. My view is through the camera in the first place, I feel like putting myself into this box (camera). Seeing through the camera does not mean looking down upon, and it does not mean I am becoming the camera either, but I would feel like that. So I am not quitting yet. I am going to photograph until I die.

“Love on the Left Eye (2014)” on purpose adds distortion and fog, or completely blackens the right side of the photographs. This is referring to the worsening of your eyesight, mainly on the right eye. How did this affect you? Did you think about quitting photography, or, on the contrary, you knew you will find motivation and ideas for new photographs even in this misfortune?

Araki: I did so to deceive the unpleasant thing (loss of sight). Haha.

Because I am one-eyed, I did an exhibition called “Kata-Me (one eye).” I don’t know why, but I prefer photographs vertically then. I physically became one-eyed. That makes me think each eye has a view of a vertical image. In fact, the worst moment I had these days, was when my right eye became blind.

First, suddenly, it was painless, and it just became completely dark. On the way to a shooting on that day, I visited the eye doctor and was told a terrible thrombus (blood clot) was in the area of my eye. As the eye doctor said he couldn’t deal with it, I went to the general hospital. Various tests made clear that the problem was the cause of blood pressure, as well as my heart was aged. There were problems in various parts of my body they examined.

Even if the blood pressure is my problem now, I am more worried about the blood clot reaching my right eye than having hemiplegia (paralysis on one side of the body). However, the idea of whether I shall go vertically or whether I shall blacken half of the film comes from my own physical condition. I thought this is mine, so just “use it!” Haha.

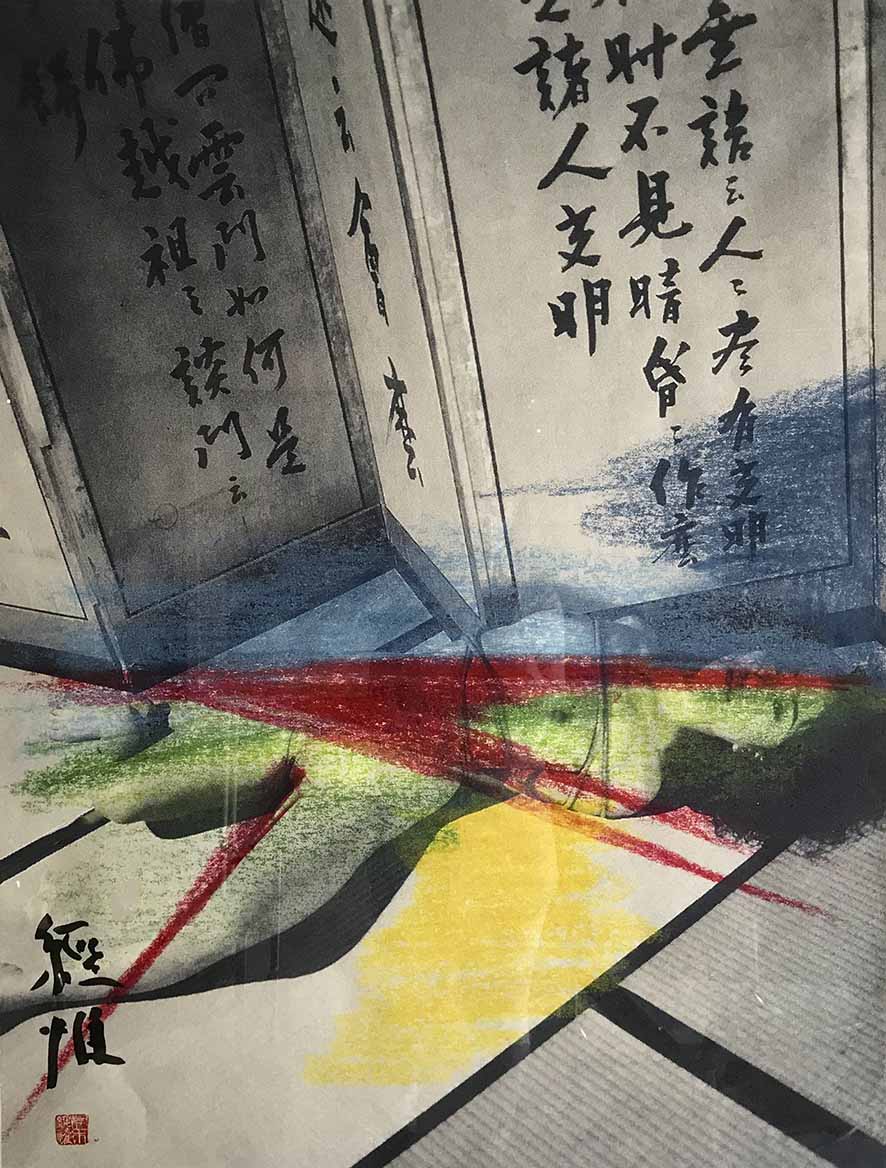

I like painting on my photographs, pretty much. That’s so cool. I do it by myself and praise it by myself. I tend to do it this way and I say so honestly. Haha.

Alzbeta: You indeed are an artist. If it was me, I would give up on everything. I think you are a really strong person.

Araki: It somehow becomes an advantage. I keep saying this also in serious times like the death of my mother, and the death of my father. But I feel that when the people, who were close to me and whom I loved very much are gone and disappeared, it may become the biggest source of my energy for photography. Such energy influences my work after time passes. Anyway, I do as I like without flinching.

The title “Love on the Left Eye” is inspired by Ed van der Elsken’s photo book published in 1954, entitled “Love on the Left Bank.” Why did it inspire you so much?

Araki: Everyone longs for his way of life when they are young. He came from Holland, met a woman in Paris, and led a fiction-like life, his ways of showing and touching. After all, Elsken, an artist, maybe liked the stories or a kind of fabrications (fiction) to begin with. I liked that and I became really good friends with him. Therefore I imitated his way.

I’ve taken a similar atmosphere in Shinjuku, my stage. I decided the title comes from “the left bank of the Seine River (“eye” and “bank” have the same Japanese pronunciation).” That’s why it’s like that. In many cases, people do not notice what my title means unless I explain something about it right away. Simply saying, such titles relate to the way of presentation techniques and the way of expression. I guess nobody wants to erase half of what is in the picture even though it is taken perfectly, right?

That’s why it may also be a tribute to Elsken. And, I also want to take my own misery towards happiness. Hahaha.

Alzbeta: What did you think about the intimate portrait of Ann (Vali Myers), on whom the narrative centred on?

Araki: I just imagine there might have been something complicated, like any other lovers. But, let’s say, when photographing, we are not getting to the bottom of something like art; we do not think anything thoroughly. Whatever, right? Things are mysterious in photography, which is better, isn’t it? People say I’m foolishly honest, but my principle is that such an ambiguity is fine. It’s not about what is wrong or what is good, but it’s okay to be vague. After all, I don’t know what is true and I don’t know what is good. Not even what beauty is. Hahaha.

How was your cooperation with Nan Goldin on the publication about subcultures in Tokyo, “Tokyo Love (1994)?“

Araki: The interesting thing is the project comes from somebody else. At that time, Nan Golding liked me, as well as in that era [or time] though – an editor said to me: “Some work by the two of you together would be interesting.” So, people around me inspired us and put us together. I think Nan is taking pictures closely and objectively. After all, her photographs reflect that she lived in the era, she is expressing her time in her way. So I thought it would be good to mix my works with emotions.

I am doing portraits of men called “Men – Naked Face” in the magazine “Da Vinci,” monthly. I don’t really want to make portraits an object (artistic object). That being said, it doesn’t mean it’s just a snapshot. So I am coming and going between objectivity and subjectivity. That’s the most traditional way of taking portraits. Even though it’s important, digital cameras omit the time to mature and deprive us of opportunities of realizing our techniques. That’s why I do not use digital cameras.

There is not one good thing about being too convenient in photography. I guess too much convenience interrupts the development process of the human brain, or makes the path of instinct missing.

On the other hand, any new creation or product of the age has a lot going for you. Come to think of it, people like us, who came dissolving developing solutions, are no match for the young, who started with the digital camera. Originally, there is an essential difference. I have a strong feeling the photography itself or the era of photography is over. I am lately writing Japanese calligraphy into the photographs on purpose. Not only some feeling of the ukiyo-e (*note: woodblock prints of the Edo period) may be in me, but I think calligraphy or handwriting is important. If something is too convenient, we lose something.

Alzbeta: Computers are the same (too convenient), right? And people forget how to write Kanji (Chinese characters) by hand. Even though everybody says how bad it is, everyone keeps using it. (Laughing).

Araki: (Laughing.) That’s right. However, then there are actually also new ideas coming from new technology.

Series: Eroquis / Eroenpitsu. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

I have had a lot of interaction with Ms. Motoo over the past year, so I would like to ask you about your cooperative relationship.

Araki: She works hard and always overachieves.

Speaking of why we have decided to work together in the early 1990s, at first she used to work as the curator of an art department at a big company, and when she organized my photo exhibition called “Erotos (*note: one of Araki’s coined word which combines Eros and Thanatos),” she displayed my museum catalogue that was published abroad (“Akt-Tokyo (1991)”). It was a “no good” according to Japanese law at that time. When the policemen came, I wasn’t there, but she was. She was taken and didn’t come out of jail for a while. She insisted: “Araki’s works are art,” and she was kept in for almost 10 days. From that time, I thought of her as a person who is really determined and has guts. If it happened to me, I would quickly apologise and be released. Haha.

(*note: At that time (1993), it was banned in Japan to publish photographs depicting human genitalia or pubic hair and it all had to be censored. However, this was considered prudish abroad, where such censorship did not exist. The book was published by an Austrian company. According to the police department, Ms. Motoo violated Japanese anti-obscenity laws. Possible violation of customs laws, which banned the import of obscene pictures, was in question as well.)

It was a time like that. We’ve worked together since then.

Now she is even more awesome. (Ms. Motoo laughed.)

Series: Sanju exhibition. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

Which of your hundreds of published books do you personally associate with the most and why? Which one do you like the most?

Araki: I like them all.

Alzbeta: I thought so.

Araki: But, after all, maybe the “Sentimental Journey (1971),” the first version of the thin one I published privately, if you ask me to choose only one book.

It relates to other books as well. I keep photographing after that, until I die. For example, I continued to take photographs on my balcony. One day, an editor told me: “If the photos at the balcony of the house you used to live with Yoko also come together, it would be interesting.” And by doing that, it becomes another good publication.

For example, the book “Sentimental Journey – Winter Journey” – the work goes up a notch because death enters. With that way of thinking, and because the whole thing is intertwined, there are around 550 of them published.

I did the “Photobook Exhibition” when 450 titles were published (“Ararchy Photobook Mania (2012)”).

Alzbeta: Among all the hundreds of published books, right after coming to Japan I bought the “Sentimental Journey – Winter Journey.” Even though I am still a young woman, the book covers everything from the times of the greatest happiness to the times of the greatest grief. In my eyes, it depicts human life. I felt all the emotions in this one book – from joy to loneliness.

Araki: The book was published because the people around me pushed me to do so. In a time when I do not feel like doing any literary creation (writing something), an editor, for example, tells me it might be good to write a little in a photography book. Then I do so. The books made by several people like that are really good, maybe better than those made all by myself.

I think it is certain that the “Sentimental Journey” is the best one to me.

Series: Sentimental Journey. © Nobuyoshi Araki / Courtesy of artspace AM

This interview was conducted at “Art Space AM“, a gallery specializing in Araki’s works. “Art Space AM” is a gallery established in 2014 by Ms. Hisako Motoo, the curator.

Ms. Motoo has worked on many exhibitions and publications with Mr. Araki since the 1990s, and is one of the most well-known independent curators and editors in Japan and overseas. Besides Araki, Ms. Motoo also promotes internationally acclaimed Japanese photographers like Daido Moriyama and Momo Okabe, as well as overseas artists.

Nobuyoshi Araki and Hisako Motoo. © Alzbeta Kossuthova

journalist