There are many photographers who focus on capturing the actual refugee crisis in Europe, but not many of them are using the long-term approach in terms of building a strong relationship to the community. Panos Kefalos did it naturally. His life is captured in life of others and his personal journey took him into the community which has already moved. What remains is their life captured with an open heart.

You studied cinematography at the Hellenic Cinema and Television School Stavrakos and photography at I.E.K. AKMI. Did you meet there with documentary photography or it is something you have explored by your own?

I took a liking to photography in my late teens. My father had bought a low definition compact camera. I played with it, without a deeper understanding of how it worked. At that time I was very interested in cinema, so after high school I opted for film studies. At film school my attention turned to still photography, because we had a great class, where they taught us how to process photos with analogue means, working with film and chemicals and all that in an actual dark room. Before finishing film school I’d already started work on my first photographic series. Less than two years later “saints.” was under way. I don’t think of what I do as of strictly documentary photography. I’d rather not pigeonhole it like that. I see it more in terms of a personal quest. A quest in which mystery holds a key role.

What was the impulse to start taking pictures?

I remember that my first impulse was to take pictures of my hometown, Athens, especially of its downtown districts. When I was there, I had an instinctive urge to document everything I felt. By fulfilling this inner need I simultaneously found a way to communicate with the people I met and establish a connection to the urban environment.

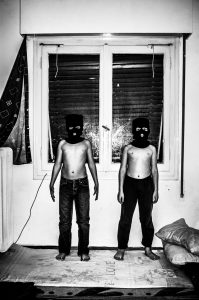

Series Saints is your key work and helped you to be recognized. Saints depicts a community of Afghans refugees living in downtown Athens. In 2016 this project became one of the winners of LensCulture Street Photography Awards. Through the kids you showed community as an inside viewer. How did this connection happen?

I began by taking pictures of Victoria Square, in downtown Athens, where I was first drawn to the subject by witnessing the way kids played. Our bond took a while to develop. I spent a lot of time with them and their families: they slowly trusted me because I wanted to be straightforward and sincere with them. That was something they understood and recognized. I was 22 when I started this project, a relatively young age. I walked around with a small camera and a flash… I did not have the usual appearance of a professional photographer. The work went through different stages. Sometimes I’d take a break because the kids and the families I knew would leave for another country and I’d lose my contacts along with the people I trusted. It would take some time until someone else would open up again. But every single time, while wandering through the city, I’d come across something that would put me back on track and jump-start the project, readying it for its next level.

Those kids faced a real evil in their life before and during the journey to Greece. Did you act sometimes as a friend and a psychologist?

I’m not sure I could act as a psychologist, but I certainly felt I could be their friend. The kids I was close to, they saw me as a friend and that’s the way I saw them too. We had many talks and I provided advice to them in many occasions. The greatest thing in this whole journey that I shared with the kids is that I had myself a lot to learn from their behavior and life experience.

You described Saints as a personal journey, that you captured your life through theirs. From my point of view, each photographer more or less does the same. What differs is the approach used. I suppose it was kind a demanding. You were working on this series more than 3 years. Did you question yourself sometimes what is the reason to continue?

Why I continued… That’s a good question. The reason I kept going stems from something buried deep inside my memory. Something from my own childhood, that came back to me after I got to know the kids and their families and the whole community. As an adult, I had now to relive those remnants of my childhood: that could prove to be a difficult task, but thankfully the creative process of photography was of great help in undergoing it. I was also dealing with the reverberations of my own traumas. I had this feeling right from the start, but it wasn’t a conscious thing at all. It was a very vague feeling. So, I went searching for the link between myself and the world inhabited by the kids. Anxiety had taken over a great portion of my life. The project provided me with the courage to keep going. I wanted to delve deep into my feelings and expose them. I felt I had to bare my soul for the book’s sake. Today I can look at the book and see very clearly the true image of who I am reflected in it.

Did your approach evolve since then?

My approach didn’t exactly change, but (shortly after the book was published) I spent a long period of time being utterly unable to work the way I used to, despite wanting to. After a brief while, my vision, how I looked at things, had shifted. I couldn’t take pictures the way I used to anymore and I couldn’t tell why. So, after two years I decided to start from scratch and strived to find a new perspective.

Some members of the community you were bond to already left Greece. Are you in contact with them?

The kids and families I was closer to, they were already gone before I was done with the project. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t carry on with the series. In the summer of 2015 Greece was at the epicentre of the refugee crisis: it was a very tough situation and connecting on a personal level was a much harder affair. The international media and news agencies were all there, journalists and photographers from all over the world: I took my last pictures and wrapped up, because establishing a new trustworthy circle of friends wasn’t something feasible under those conditions. I am still in contact with some of the kids via social media, especially lately. I can see them growing up. We used to talk on the phone or via Skype but very soon they forgot the Greek they spoke, so we don’t do that anymore. With others I eventually lost touch. The kid with which I get most often in touch, he speaks English.

Did you think to elaborate Saints also abroad?

I knew from the very beginning that I wouldn’t continue the series abroad, that I wouldn’t travel with these families to their next destination. Ending the project in Athens, since it all that started there, seemed the right thing to do. That’s why I included a small booklet in the volume, where, by relating some of the kids’ personal stories, I take the opportunity to explain what saying goodbye to each other meant for us. It was very important for me to end the book this way, with this section that I called ”Valedictions instead of an epilogue”.

In 2016 Fabrica supported you to publish a photography book Saints. How did you feel holding such proof of your work being materialized?

Seeing the project take form in the shape of a book was very important for me. That the end result should have been a photobook, was something I had very clear in my mind from the beginning. Fabrica and Enrico Bossan – who contacted me – specifically, showed me they believed in me, boosting with their support the difficult work that was underway. I feel very lucky and grateful for the completion of the “saints.” volume. I learned some pretty important life lessons from our collaboration.

You story Lava is a private diary and your perception of Athens. It is shot in color. Why?

I prefer long-term projects, in general: the material I collected in “Lava” comes in large part from pictures I did for the Greek edition of ”Vice”, where I am employed as a photographer. It was also an evolution of some of my own snapshots, ones that I took in downtown Athens, documenting both my daily life and the day-to-day living of those around me. It’s really a product of my wandering through the city. The first pictures I chose to include in the project were in colour: consequently brash colours gradually came to define more and more the visual style of the series.

What do you think is a role of a documentary photographer today?

Working on ”saints.” I felt that I needed to deeply respect both what I had to do and the people I was photographing. The risks I take in my work should only concern myself and never expose anybody else but me.

We have featured several contemporary Greek photographers with expressive approach at dofoto, e.g. Georgiadis, Simou. Is such visual trend common in Greece now?

Yes, I noticed the interest you take in this current of Greek photography. I know Ilias Georgiadis very well and we’re actually good friends. It’s been some time now that this approach is one of the dominant ones in my country, but I think it’s a much broader tendency, that goes well beyond Greece. Artists having a shared sensibility is a beautiful aspect of creative work. Nevertheless, creative people shouldn’t neglect to explore and cultivate their own personality, because in the end trends do fade: when all is said and done all that matters is an original voice.

What is your current assignment and what are your near and long-term goals?

As I mentioned before, I spent a long time without being able to take pictures. Now I’ve come up with a different perspective on photography and I could say that it is like starting from scratch. It’s been a year and half that I’m either researching or photographing for this new project, even if I was unfortunately forced many times to stop, because of various circumstances. Now it’s rolling again and I’m mostly editing and reviewing the material I have collected up to this point. It’s an experiment, to be honest, and only time will tell if it works.

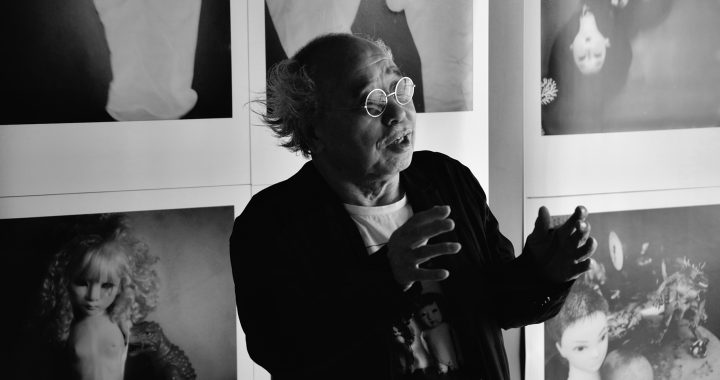

Panos Kefalos (*1990) was born in Athens. He has studied cinematography at the Hellenic Cinema and Television School Stavrakos and photography at I.E.K. AKMI. He was selected in 2013 at the Athens Photo Festival in the Young Greek Photographers. In 2014 he was shortlisted for the Leica Oskar Barnack Award.His project “saints.” was supported by Fabrica, Italy and it was published as a photobook in July of 2016. “saints.” got selected by Jurors’ picks for the LensCulture Street Photography Awards 2016.He won the Gomma Grant 2016 Best Black & White Picture award and “saints.” got selected as one of the Top 14 Photobooks of 2016 for the LensCultute list.He won the 15th Reminders Photography Stronghold Grant.In 2017 he was selected as a finalist for the second annual Magnum Photography Awards with his project “saints.” and the LensCulture Street Photography Awards with his project “Lava”.