Words are marvelous and yet so complicated, aren’t they? Because they create boundaries/distinctions and then they have the potential to isolate us.

Boundaries; the malleability of home, identity and nationality as they intertwine within our bodies; the ineffable and amorphous understanding of self throughout history; isolation; loss; these are the complex and fundamental truths that Lesia Maruschak investigates and dances with through her work. As such, to write about Maruschak’s work is like trying to catch fire; no sooner have you gotten over the burn than the flame has evaporated from your hand and you are left with a the foggy memory of an acute, emotional sensory experience.

Maruschak is a photographer, yet such a title is an oversimplification of her practice. While photography, both practical and archival, has been a jumping off point of her work, she is ill content to limit herself the to strictness of the traditionally understood documentary photographic image. Maruschak recalls her early inclinations to paint on her photographs, recollecting.

I was talking to my colleague [saying] I’m painting on my photos now – using egg tempera, pigments and wax. He [askes], ‘why are you doing that?’ And I said, because they’re dead. That’s it. To me, they’re static… You see, I’m very interested in materiality, rhythm and connection. That’s really important to me. And I’m also interested in the audience and how the audience is going to experience [the work], how they’re going to be affected and engage in the works and the space – become part of the making. So, for me to take something and put it behind glass makes it very static, difficult to connect with in a sensual manner and I’m very interested in something that’s alive.

Maruschak’s piece, “Maria,” which, “memorializes the victims of the 1932-33 famine in Soviet Ukraine – Holodomor – an event widely thought to be genocidal [through] a single vernacular image of a young girl who survived and resides in Canada…” is a continuing chapter from her previous artistic photographic investigations of Holodomor as seen through her works, “Red,” “Transfiguration,” and “Counting,” and distills down the incomprehensibly casmic lost of life and liberty through the vessel of one survivor, Maria. But “Maria” is not a straightforward documentary piece, rather it is a waltz between the Maruschak and the idea of a woman, grounded in reality, named Maria, through opaque time, each questioning the other; what is truth; whose memory is this; whose body resides within the work? Through “Maria” fact and fiction are blurred without ever losing the integrity of truth.

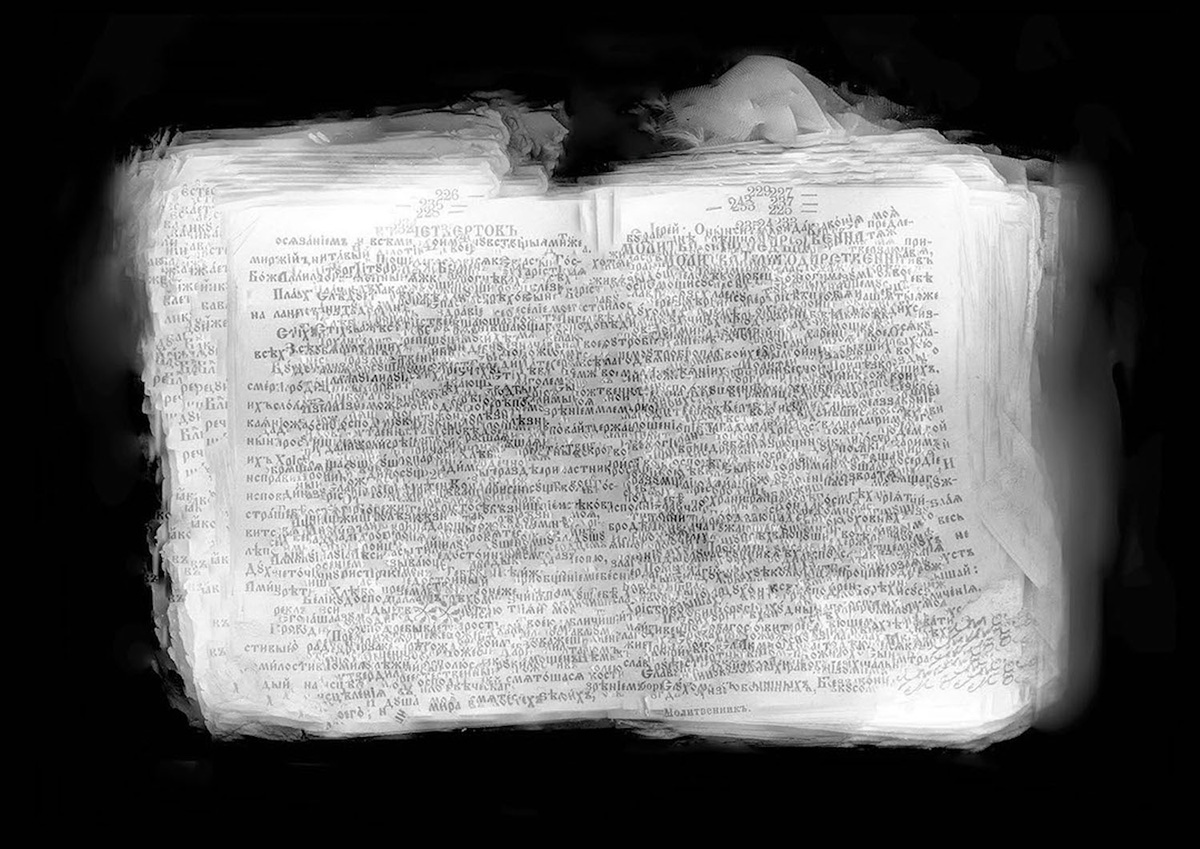

Maruschak, a photographer intensely interested in photographing the ineffable invisibility of our experience of history, recalls the original understanding of the photographic image at its inception in the late 1800’s through her treatment of photography as an pliable medium, rather than a static document of proof.

Many of us in the documentary photography industry are settled in the assumption that photography has always been understood as photography, that straightforward practice of documenting the proof of events for which purpose our industry was bestowed in the mid-20th century with the rise of photojournalism. But at photography’s inception, photography was actually understood and called “photogenic drawing.” The difference between an image drawn with light and an image drawn with ink was philosophically, for a time, indistinguishable.

Later, as the industry developed and grew, this photography as a “document of proof” barrier came up from the ground, only to be yet again demolished by the digital photography revolution which now, in a serendipitous revolution of intellect, challenges photography’s previous self-identification as “proof” as images made today through the digital lens are no longer automatically trusted.

Maruschak’s work is so important within the context of our current visual storytelling landscape because she is a photographer with an old soul in search of Truth, regardless of boundary, restriction, and who is allowed to ascribe definition. Holodomor does not need to be proven, it needs to be understood.

Consider the challenges of photographing a history such as Holodomor; the very facts of the event are ever under debate; the exact number of lives lost will forever be unknown, rather being relegated to an estimation, and the effects of this genocidal event on the very fabric of society are subjective, complex and have rippled through time to our contemporary experience of them; denial of the event is still a powerful voice in some corners of the world, and the voice of experience has been silenced throughout generations, whether through social requirement or the extinguishing of life itself. Faces are lost, propaganda is manufactured, and photographic documentation as proof underwent a kind of genocide as the archival photographic image were destroyed by state agencies to deny the facts of the genocide to history.

And so, Maruschak’s work, instead of presenting static facts and figures in a straightforward, traditional documentary manner, dances with her work, mapping out the movements of a women contending with tragedy on an unimaginable scale. Maria is not just one young girl that survived the Ukrainian famine, she is the composite of every person subjugated to the those unimaginable conditions who Maruschak works to understand; to every voice that was silenced, either by political will or historic circumstance, and Maria is the version of Maruschak that is ever sewn into her body of work.

I was moved on emotional and intellectual levels… I often ask myself: Who are we as global citizens? What is our relationship to the past? Who are we in the present, to each other, what responsibility do we hold and how does that point to the future?

It is not only Maruschak’s practice that dances with her subject, it is her presentation of these themes as well. Maruschak repeatedly goes back to Raphael Lemkin’s assertion that, “The function of memory is not only to register past events, but to stimulate human conscience.” and so Maruschak takes her practice one step further in the dance through the creation of a photography book, “Transfiguration,” as well as a traveling memorial spaces in which she exhibits her work. Where memory is inherently ineffable, Maruschak produces objects and builds gllobal spaces that bring physicality and movement to these stories of old in an effort to preserve the lessons within.

I’m interested in many things. I’m interested in the manifestation of evil… Now that is a complicated word. I’m thinking of events, historic and current, where statistical facts are absent, misrepresented and we can’t even know the number of dead – scales of loss of life that are simply unimaginable. I’m committed to facilitating global conversations and that’s why I’ve created something that I’m naming a mobile memorial space… I’m interested in our responsibility to the past, to the future, and to each other… This is the vehicle that I’m using to manifest that narrative.