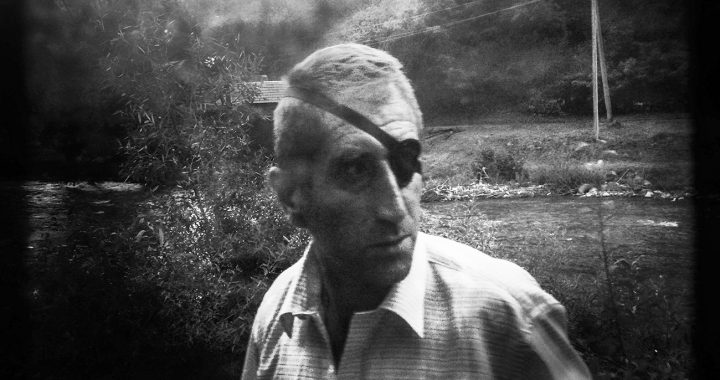

Antonin Kratochvil‘s work is significant for a legible handwriting with a focus on dynamic work with light. He is rightly regarded as one of the top 100 most influential photographers as of late. After fighting with death, Kratochvil has returned back to the scene and currently helps to resurrect Czech documentary photography. Talking to this person has been a great experience for me, I thank him very much for this.

We can start with a book from a circus environment because after all, isnt everything all a really big circus? And what interested you about this topic?

I was twenty-five years old and I was very interested in the environment because of the unique oddity, and generally, it was a beautiful topic with interesting characters. It’s been in the archives for a long time, and we`ve decided to do a book release just recently on this subject.

You have been documenting returns to totalitarian regimes for a long time, publishing them in a book Broken Dream. How did it feel like?

I photographed it from the early 1970s until the mid-1990s. Of course, nowadays, it’s different for photographers, the system has changed. But back then I had to wear the camera under the coat because the police were aggressive and if they saw I was photographing reality, they would start to restrict me or just take my film. That’s when I felt like James Bond of photography. Today it is about something else. Maybe just somewhere on the edge of Russia, we would have met with such bureaucracy.

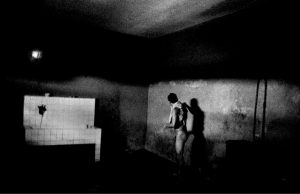

This project is visually very dark.

There was not much of the “sun” back then, the rain was polluted and I picked the environment where I sensed this atmosphere. For example, I came back from America to photograph November events so I searched for it over the radio. I made a photo of Brezhnev at a bus stop where there was a minimum of people, but it was more interesting because they were banishing his portraits.

Traces of Robert Frank. How did you come up with this idea?

Robert Frank’s photographs were critics of the society and so he could not release this book in the US. It was published in Europe. I traveled through America and today it’s all “different”. I understood it my way and got to know America by visiting completely forgotten places. I started the trip on the same day as Frank did fifty years ago, basically, it was a coincidence and I did not do this project for any customer.

Haiti is shot in color. Why? The reportage is very dynamic and contagious. How did you create it?

It was for The Times Magazine and they wanted to publish it in color; in Haiti, you just have to shoot in color. I used my previous experience and said to myself I had to do it differently because most photographers there had long lenses and I chose my favorite lens twenty-eight. It was very dangerous because, as we know, terrible things were happening there.

The book “Moscow Nights” is intimate. How was it to meet personally this wealthy youth?

Basically, nobody wanted to go there. I photographed it for Vanity Fair, and they knew the magazine and wanted to be published in it, so the guys who were there in charge let me in. I processed the idea from those partying until the early morning to the workers who have to go to work every day at that time. It was important that I was not only around those women and just taking pictures of them. Then I got into their intimate zone and they tolerated me, even though there were a few aggressive Muslims, whom I did not give a shit about and just photographed my stuff.

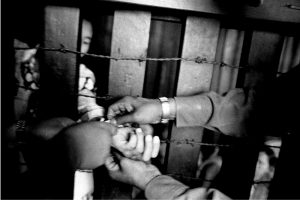

Photographing in prisons. What led you to this topic?

It was tough. The San Juan Prison was the roughest prison project. With my camera, I got to the places where even the guards themselves were afraid to go and they just let me “swim“ there. Gangs were created there, ruling over everything. They allowed me to photograph certain parts of the prison, but later it was very complicated because of the bureaucracy of the local guards. They did not want to let me in for their sole purpose of keeping me from seeing this grotesque reality. It was very complicated, but sometimes, the guards were so drunk that they disappeared somewhere. I pursue this opportunity to capture some of my best work. It was my project and I wanted to show the worst prisons. I was very interested in it and I waited a very long time to get the permission, but eventually, I could shoot for a few months.

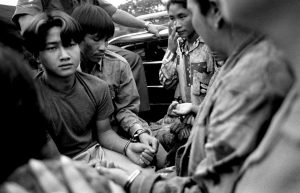

You also won World Press Photo with the Burma Heroin series.

Sure, it was a prison in Burma. I was shooting a report for the NY Times about drugs. It was really crazy and very interesting there. I search for similar topics, it simply fascinates me.

Those photos are very artistic. How do you perceive the position of today’s photojournalism?

In my opinion, it was affected by the digital. With the analog photography, we had limited space, and we really had to know what we wanted to photograph. With digital cameras, you can take numerous pictures, and photographers rely on the fact that something will come out of it. Photojournalism has been greatly influenced by the technology. It’s a totally different approach. If we look for example at Sebastião Salgado’s contacts, we see which photo he chose as the main one, but that approach is already very precise while taking pictures.

Portraits of Bono from U2 make a series. How did you make it?

Time Magazine addressed me, along with James Nachtwey, to portray the personalities they preferred. Nachtwey chose the head of Microsoft and I photographed Bono. It was a secret, and I spent fourteen days on roads with Bono.

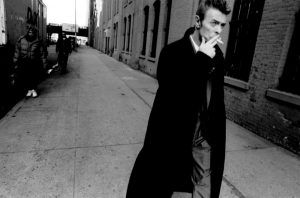

There are many important characters in the Persona book. Who was the most complicated?

Well, they knew my work and they liked it, so they kept choosing me and it was a very interesting period of my life. For example, David Bowie has asked for twelve portfolios of the most prominent portrait photographers, and finally, because of my work, he chose me.

Columbia Cycling is a sports theme project. How did you get to it?

I got there through one South American magazine Outside and they wanted a photo report about the cyclists from Colombia who started to promote themselves in the world at that time. It was really interesting but also dangerous because they were driving in areas where FARC bandits were routinely kidnapping people. But they let cyclists be, allowing me to do the job without a risk. I took this series as a documentary about the country in which cycling has just begun to be popularized.

You shot for the National Theater in Prague. When will the book be published?

I finished it already, it was about shows and the book did not come out yet. I hope it will work out because the photos are very good. I am currently completing another AK47, it is a selection of photos from conflicting zones and the book will be very extensive, you can look forward to it. It will be published in December.

I would like to return to the war photo, specifically to Iraq. There you have moved the visuality to the diagonal. When did you get this idea?

I do not even remember how it started, it was such a long time ago. But basically I photographed in the desert and I needed to work with the horizon so I started to tilt the camera because I wanted to make this series more dynamic and it pleased me.

Paolo Pellegrin was there with you as well?

Yes, we were traveling around Iraq and tilting cameras together. At that time he was young and I became a sort of idol to him. We both like dynamic almost expressive photography and I am glad that Pellegrin continues to shoot this way.

What do you think about photography schools? Does it make sense for documentary photographers to go to study?

I have lectured photo reportage in a private school, and unfortunately, there was not a big interest in this subject. It was as if the young people lost their social sentiment and avoided social issues just as in the past. It is very demanding for both psyche and time, and now everyone is on the mobile phone and has other priorities. Social thinking has completely changed. Everything has changed. Everything has changed in Europe. Nowadays, you can not capture interesting people without their permission, because laws have changed to the detriment of photographers. So they have to go to photograph somewhere in Asia or Africa.

Why is a documentary photo in such position? Today, everything sketchy is called a document.

There is being created some conceptual photography that has nothing to do with the document because the documentary photo is about the connection of people in the topic. You can not find it amongst these conceptualists who are called documentarists. There is a lack of humanity and the relationship to the topic in depth.

In Prague, you met Jan Grarup with whom we also had an interview.

Jan is a really good guy and I tried to get him into Agency VII. Unfortunately, it did not work out because of personal relationships. That is a pity.

Antonin Kratochvil was born in 1947. In 1967, during the totalitarian regime, he decided to flee from Czechoslovakia via Yugoslavia to Austria. He came through Traiskirchen refugee camp, a prison in Sweden, The French Foreign Legion and finally ended up in Holland. He studied photography at Gerrit Rietveld Academie. After finishing studies, he began working professionally in the US, where he cooperated with magazines such as Times Magazines, Vogue, Rolling Stone, Newsweek, etc. As a photojournalist, he worked in war zones and conflicts all over the world. He received three awards at the prestigious World Press Photo. The book Vanishing won him an award for the best documentary photobook in the US, and in 2005 he was awarded the very prestigious Lucie Award. Antonin Kratochvil is a co-founder of photo agency VII. He currently lives in Prague and works on a new photo agency 400 ASA.

All photographs in the article © Antonín Kratochvíl.