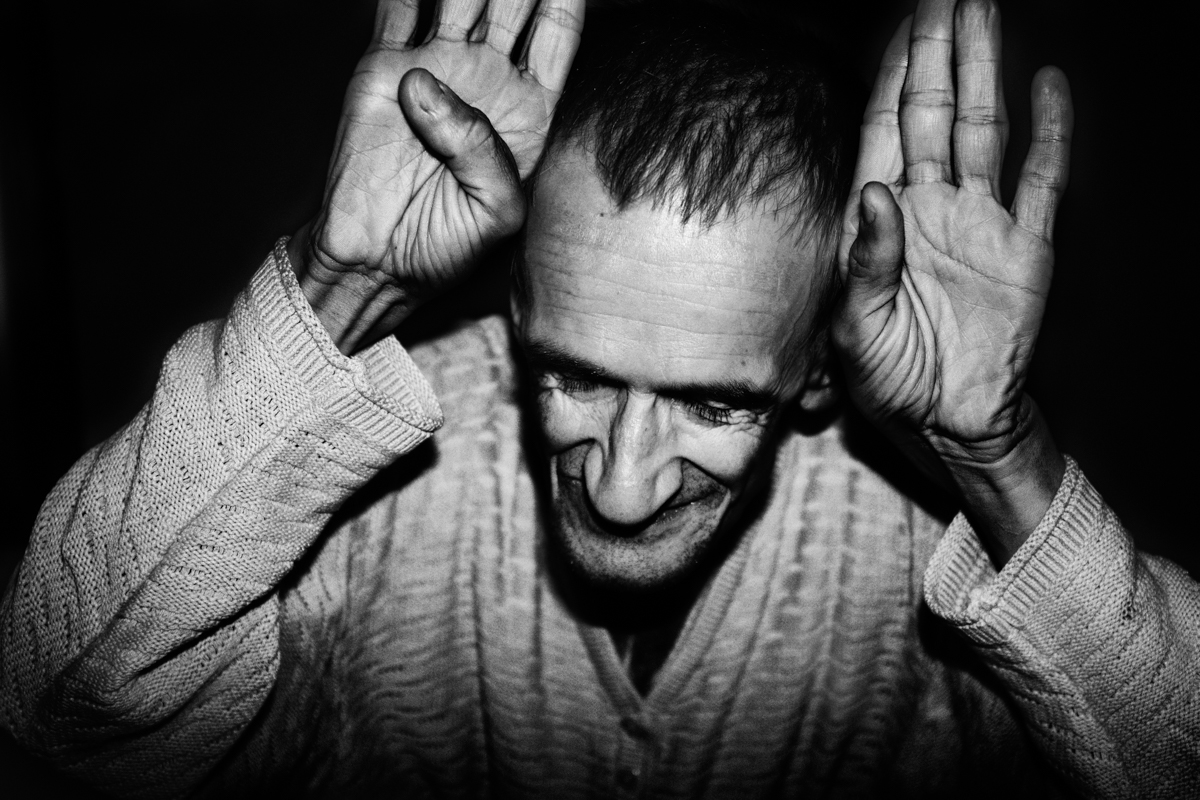

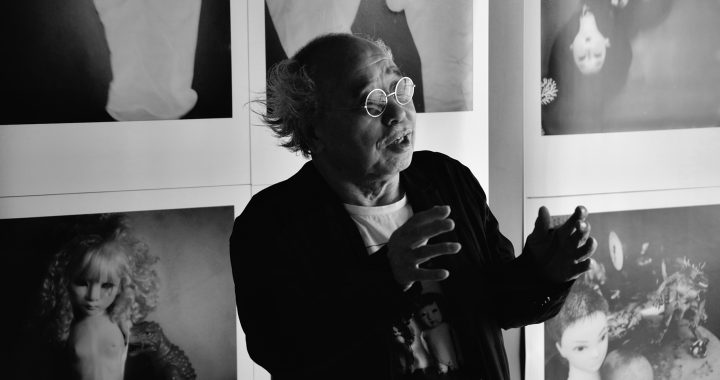

Photographer Scott Typaldos uncovers the dark side of treatment of human beings. Since 2010 he is devoted to the topic of mental illness in his long term project called Butterflies. His visual is straight and hard-hitting, as a bullet finding the right target in our mind and it looks like there is no distance between him and photographed subjects. We`ve talked about his approach to such demanding project and documentary photography.

You studied movie editing at film school but turned to photography. Why?

While studying filmmaking, I spent more time in the darkroom or shooting than making movies. Looking back at it, I think I favored photography because it gave me more freedom and autonomy to create something on my own. I could take pictures whenever I wanted without any dependence. I did not like working in teams. Filmmaking involves a lot of planning and in those days, cost a lot of money. I did not have many ideas for narratives. This aspect has since changed as there currently are many stories in my head. I studied filmmaking too young and lacked the necessary experience to tell incarnated stories. The situation has inverted itself and I have been more active in filmmaking in the last years. I now feel burdened by photography’s limitation to construct complex stories. I know that currently photography is moving towards narratives but I feel that most attempts rely on tricks which make the medium’s shortcomings even more apparent.

What do you think should be the role of documentary photography and why did you choose it?

If I project myself in the role of a documentarian, I think obsession has been a key factor. There is an impulse to deepen, twist and exhaust a certain raw matter that finds its source in reality. I’ve noticed that my definition of documentary photography was often contradicting its general definition. To me, its role in society is not to inform or clarify the state of things and has little to do with news. It is not a form of activism either. Documentary photography should not hide itself behind ethics, advocacy, politics in order to hide less righteous perversions or inexplainable compulsions. Describing a subject as I experience it whether controversial, shameful, unacceptable or immoral is important. The more I spent time documenting mental illness, the more it forced me to face the vagueness from which my naive desire originated. I was forced to clarify my intentions in order to keep on working. The most difficult aspect to digest is that you often document yourself using others as indicators or reflections of yourself. This egocentric tendency has to tame itself, as when it is all done, it is the balance you have found in your human links that gives meaning to the work.

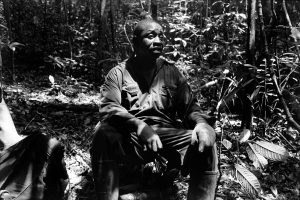

Did the shooting of the series In the Back of Beyond [men looking for oil in Gabon, Ed.] change your approach to your creation? E.g. moving from diary to long term?

In the Back of Beyond was the first strict documentary which I worked on. Before it, I’d been shooting in a diaristic manner. Both pertain to facing certain realities but my trip to Gabon was the first time I really extracted myself from my social and economic environment. The sheer act of being where you are not supposed to be modifies the emotional angle from which you perceive reality. In this regard, In the Back of Beyond was essential. It forced me to compose with strangers and work on the uncanny, surrealistic, but deep affective links which you build in a place out of time. Paradoxically, it was by facing an element I knew nothing about that I found new means of expression. This work also showed me that subdivisions and genres of photography did not exist for me. A diary photographer uses the same distances, has the same desire for connection and desire to go deep wherever and whenever he faces a person.

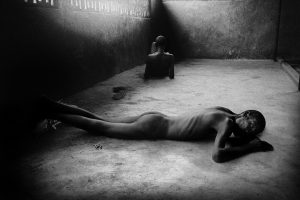

What was your aim in Ghana [series Butterflies I., Ed.] that time and now? Do your goals evolve based on your experience?

I left to Ghana right after a complicated time in my life. I had no plans except a strong desire to photograph two subjects: death and mental illness. I had done no research nor planning and I had absolutely no idea on how I would reach my goals. On the field, the stars seemed to be aligned in my direction and I worked as If I had absolutely nothing to lose. It was a very stimulating time although highly intensive and draining. This energy laid the foundation of my Butterflies work as I quickly became profoundly taken by mental constructions and their dysfunctions.

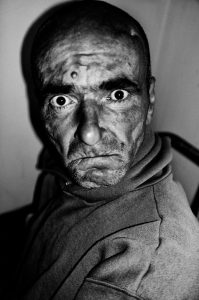

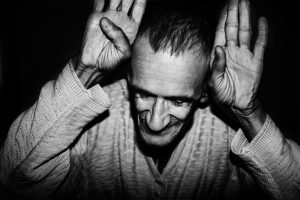

Comparing the way I worked on mental illness then and now, a lot of facets have changed. The most important one is that I no longer have any innocence regarding the subject. I don’t get impressed by decompensated psychological states anymore. At first, observing psychoses is immensely provoking and rattles your nerves in disconcerting ways. When Your emotions are in the way, you are forced to work within the mental illness and take part in the situation. With time and experience, I generally thrived to take a bit more distance to achieve more clarity. Mental illness’ visual symbols (open mad eyes, strange body postures, grimaces) are strongly anchored in our culture. It is rightfully so as they do exist but the most interesting part of psychological turmoil is much more complicated to describe photographically. Currently, the images that I am drawn to are more indirect and require more observative precision. I’ve become increasingly interested in people’s motifs and much less in the photographic exercise. Making a strong image is less important than it used to be if it betrays my observations. To conclude on the differences between the project’s beginnings and now, I’d say that it is less romantic, adventurous and superficial. It took me a long time to feel the weight of what I have been photographing. Carrying this burden is more complicated for my own psychology but it has allowed me to evolve. Field experience destroys certainties which are replaced by an indomitable cruelty in front of which you lose your certainties.

You shoot in black and white. I understand that it helps to visualize psychic state of subjects much better than using colors, but did you also think of using it?

I use color especially in an experimental context. In a way, I think that I’m preparing for what will come after Butterflies. I think that after this project, I will not be shooting in black and white anymore because I feel too comfortable and contrived using it. I started Butterflies in black and white and I’ve not found a convincing enough reason to move the project towards color but I do not agree that black and white helps visualize mental illness more than color. I think that colors can also work but my problem is about mixing the two. The lengthy work and determination involved in entering mental institutions do not allow for much experimentation as the hospitals’ door rarely stay open for long. If you work in an immersive way, you soon become a nuisance for the institutions’ working staff and you need to use your time efficiently. It is not a good moment nor place to try to revolutionize your visual language. I try to concentrate on the people and I know that technical complications or experimentations often get in the way. Everything that turns you more into a machine needs to be contained. Moving to color would make my project fresher and newer but not necessarily more essential, profound or coherent.

Today with the growing amount of information and news is hard to focus on one particular topic. Is society even interested in problems of others?

I do not know what people are interested in. I suppose that it would be easy for me to lament myself on the general lack of culture, the rampant individualism, shallowness or superficiality but I also know the world is more complex than ever. Regarding the subject of mental illness, I feel that many people are interested or directly concerned by it but that even more are terrified and want the issue to remain taboo. I sometimes think that mental illness is a black box containing societies’ most crucial information. Its existence reminds us of a crack that we instinctively try to hide in order to survive as a civilization. Asylums question the very nature of what normality is and the sacrifices “sane” people have to make to protect their vulnerable structure.

Emotionally, what was your the worst and the most demanding photographic experience? Series Unsung [room filled with dead corpses, Ed.]?

No, Unsung was not particularly demanding. I had a five minutes access to the morgue and I shot everything in total darkness. It was provoking for sure but dead people are quiet and harmless. If you do not believe in ghosts, there is little stimulation except the one you let your imagination create. I actually felt quite peaceful when I shot this series. It is one of the luxuries of being traumatized and dissociated. It felt like a dream.

The most demanding photographic experiences were all part of the Butterflies project. Chapter one was the most difficult chapter on a physical level because I worked a lot in hard heat with very little money. I felt ill and lost a lot weight. Half of the time I was there, I worked in a febrile state.

Chapter five which I shot in the Philippines was the most difficult psychologically. As soon as I arrived there, I realized I could no longer nor wanted to work in the way I used to. My certainties completely vanished and I worked with a feeling of being abusive, uncompassionate and illegitimate for the entire process. It affected my capacity to make links during portrait sessions. This phenomenon came from my refusal to romanticize anything I was shooting. I wanted more intellectual distance and suffered from the process as it is not natural to me.

Your creation often uncovers the dark side of treatment of human beings. You provide us pictures of dissociation, decay and sometimes hopelessness. How does it influence you personally?

It changed my intellectual and emotional structure to an extent I am still assessing as it often unfolds inside me in an inextricable way. I do not only mean that in a negative way. Observing mental illness brings you closer to what humanity is made out of in opposition to what it pretends to be in “normal” societies. This closeness brings moments of incomparable joy which extract themselves out of reality and time as a rare perfume. These feelings and moments never translate into photographs but are the main reason why I continue despite the complications.

Your visual is straight and hard-hitting, as a bullet finding the right target in our mind. It looks like there is no distance between you and photographed subjects. I think this ability is a key in documentary. Have you ever felt the disability of finding a connection between you and the subject?

It is very rare for me to feel I’ve achieved a fulfilling connection with my subject but I try. For some individuals I encounter, connections are almost impossible. The nature of certain illnesses make emotional contacts very complicated. In these cases, you need to connect on another level that relies on instinct, emotions and intuitions. There is sometimes a great inequality between my ability to process what I am feeling and my subjects’ inability to do so. The act of provoking a raw emotion or attempting to make a link, when the person is not armed to have one, can be dangerous and sadistic. How far you are willing to go depends on your ethical grid, confidence and drive but you can quickly fall into abuse. Individuals suffering from deep psychological turmoil are the most vulnerable population group and working with them is accepting to walk on morality’s margins. In these cases, photography cannot be a goal in itself. It needs to be an excuse, a secondary activity.

What is the motor which forces you to continue?

I am not certain for sure. Perhaps that it has something to do with events that happened in my youth. A desire to understand something or to prove to myself that I tried hard enough to deserve a bit of serenity. Foremost, I really enjoy doing it and keep on learning a lot from it. It is demanding and frightening but there is nothing as stimulating.

Your pictures have been accompanied in publication of MONO volume two [by GOMMA Books, Ed.] with great photographers like Miron Zownir, Matt Black, Giacomo Brunelli, Daido Moriyama and others. Do you plan to publish your own photography book?

Yes when I’ll have finished shooting Butterflies, I wish to publish it as a comprehensive book. I am not in a hurry though as I would like to do it well.

Tomasz Lazar during an interview told me that the raw reality does not exist and it is just a matter of our perception. Do you think that each photographer creates his own type of reality?

I do not know what reality is. What I know is that I’ve tried to push my subjectivity through the years. There might be a common matter that unites us all although it is difficult to prove. It is a question of faith which cannot be argued. Perhaps that every photographer is intrinsically subjective. When they say they are not, they are found out to be, especially when their practice is demystified. Some photographic institutions are desperately trying to protect facts using reductive rules or dogmas. I feel it as a desperate attempt, made up of a strong denial of the times. The function is to protect the representation of photography’s political power. A less reactionary approach would be to finally admit photography has no more claim on truth than a painting does. Anarchy, uncertainty and confusion are difficult truths that are often sacrificed for order and simplicity. For these reasons, I feel that current photojournalism is further from reality than is often admitted. It is true to facts but not necessarily to reality. It pretends to truth by omitting reality’s complexity. If there is a reality, it cannot be simplified or reduced nor controlled, it has to exist within the chaos.

What is your near future and long term plan?

I’d like to finish my current project and publish it as a book. After that, I’d really like to direct a fiction film using a story that I have extrapolated from field experience. I also want to direct film documentaries. My next photography project will be in color and might involve less planning or research.

Scott Typaldos (*1977) was born in Switzerland. Coming from a filmmaking background, he turned to photography at the end of his studies in 2001. His first active years were dedicated to diary and intimate projects. In 2005, his documentary on oil searchers in Gabon shifted his focus outside of his close circle. Since 2010, he has been extensively photographing and researching the topic of mental illness through his long term project called “Butterflies”. Scott Typaldos’s work has been awarded and shown in numerous countries. Since 2013 he has been a member of the Prospekt photo agency based in Milan.

All photographs © Scott Typaldos