Thanks to Prague Street Photography Group, we have been able to prepare an interview with one of the most significant war photographers in the world today. If you are interested to meet Jan Grarup personally, do not hesitate!

On 4th October you are about to have a lecture in Prague in the DOX Centre for Contemporary Arts as you were invited by Prague Street Photography Group. Which project are you about to present to the audience? Have you ever photographed in Prague?

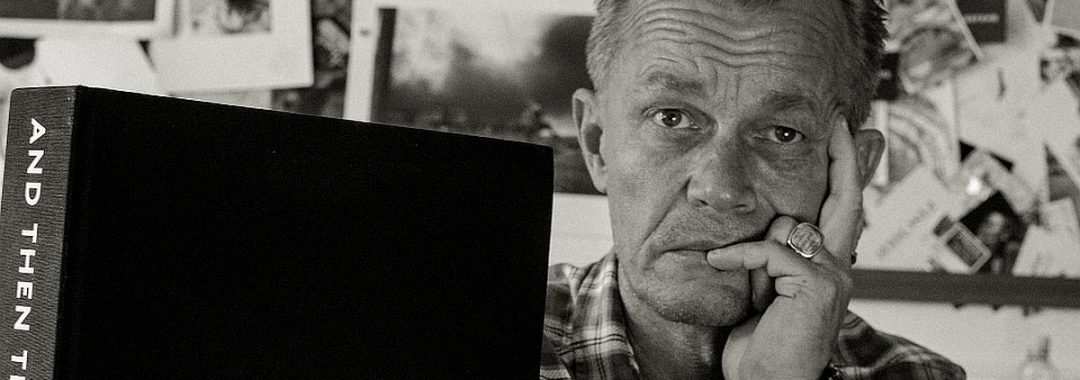

I will present new work from Somalia and show work from my book „And Then There Was Silence” and tell the stories behind the images. I have visited Prague several times, even when I went to photography school when I was 17 years old. I love the city.

You were born in Denmark, how do you perceive photography in northern Europe?

Photography is developing fast in Europe. We have a long tradition and many look to the classic photography like myself. But on a more artistic way – art photography is developing. In photojournalism things are also moving. The longer stories, in-depth reporting is crucial, many things are changing in Europe and photographers have a voice in documenting this change.

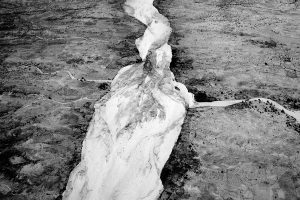

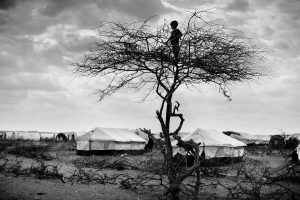

Your black and white photographs in some essays enhance drama and emotion without the distraction of color. Why have you decided for black and white instead of colour palette?

I have always felt that colour photography “pollutes” my images. For me the expression in faces tells a story. I want people to focus on this. When I do colour work there are many distracting factors which “weakens” the final work. Other photographers master colours fantastically, I don’t. And furthermore I feel that my work being in B/W removes itself from the fast forward news media of today. Once it is in B/W, people instantly know this is something different.

Which things do you consider important in photojournalism?

Today everything is possible in a computer. There have been numerous cases of “photoshop fraud”. Being honest in your work and being a human, is the most important. People need to trust the photographer and his or her images. Besides this, I urge photographers to remember that whatever subject they photograph, that we as photographers have been shown trust in being let in to other people’s lives. They are not subjects for us, these are real people with real stories and we need to honour this. They are not just figurants for us.

You have photographed tragic stories back in Africa. Are there any motives that you do not want to photograph again?

There are many images and situations I hope never to see. But the way the world looks today, I fear that I will see it all again. We live in a world that is divided. We are building a fortress Europe, Trumps wants to build a wall, people live in massive poverty around the world and look for a better life. There are more than 65 million refugees in the world today. So to answer your question – many things will happen again.

Your story on Rwanda in the book „And then there was silence“ is not easy to handle both physically and mentally, it’s hard to ignore those photos. What is according to you the responsibility of photography towards the world?

My photography from Rwanda during the genocide is a testimony. It shows brutality and atrocities. I am not an artist, I am your eyes. I document what happens in front of me and tell the story. Hopefully my images from Rwanda will stand as a document on what the world looked away from while it happened.

How has it felt like to photograph looting in Haiti? Have you felt a risk of losing your life?

The looting after the earthquake in Haiti was not about stealing, it was about surviving! Yes, it was very dangerous, but at the same time it was important to document because help from the outside world came late and too little. When you do what I do as a photographer you need to put yourself in these situations even if they are dangerous.

The drug topic in Kabul is photographed in color. Those are very personal photographs. How did you get there and what was the main trigger to document this topic?

I worked many times in Kabul in Afghanistan. I was imbedded there 17 times during the latest war. Drug addiction is a major problem in Kabul and it needed to be documented. Gaining access is all about being honest with the people you meet. Once they understand your motivation to photograph them it is much easier. But you need to put yourself “out there “ for it to happen. It doesn’t just happen. It is hard work.

Do you collaborate with media editors on stories?

Sometimes, but I prefer to work alone without interference from editors or magazines. I finish my stories when I feel they are finished and not when a deadline dictates it.

Many terrible things are happening all around the world, but the big problem in Europe is the immigration crisis. What is your opinion about it?

I already touched on this issue in a previous answer but for me personally immigration and the way Europe reacts are one of the most important issues in the world today. We are seeing people drowning in the seas daily, some people think it is okay, but I don’t!!! We have a responsibility especially when you look at your history. Often I feel ashamed by our politics in Europe. And photographers have a crucial role in documenting what is going on.

War photography has a tradition. Since Fenton, many important authors have documented war conflicts. Have you ever had any icon, or are you a long time friend with any of your colleagues?

I have many good friends who are among the best conflict photographers in the world. I also have taken part in many of them being buried after getting killed in the line of their work. It is a dangerous job. Fenton’s work in Crimea was the first important work in a war zone. For me one of the best photographers in conflict was Larry Burrows. His work during the Vietnam war was so important and strong. For me he is one of the very very best ever.

Since you were awarded in the World Press Photo contest, what is your opinion on photographic competitions? Do you think it is meaningful to participate in them?

I won eight world press awards and many other awards, more than 300 internationally. They don’t mean anything to me. I find it more important to touch “normal” people with my work than the industry. Having said that, awards can put a conflict or a story on the agenda which can be very important. But humane photography should never be a contest.

Your photographs touch death and darkness in today’s world but are also deeply connected to religion. Do you think that photography today can still be a tool for helping?

Religion is a key factor in many conflicts. Religion has killed more people than you can imagine. It is important to remember that another factor is ignorance and we should all take a minute once in a while to think about how we address issues before we either talk or react. The key word is talking together and trying to understand.

You have seen a lot of suffering, human despair, death, and pain. Can you, or do you want to forget?

I have seen many things I will never forget, nor should they be forgotten. It is important to remember. Also if I ever came into a situation where I didn’t react as a human to what I saw I would stop.

Photography is made by a photographer, but is it all it takes ? Who are you?

Photography is tool, the important part is who carries the tools. It is all about humanity and the eyes that see. You need to be there, you need to put your heart and mind into the stories to understand or at least try to understand.

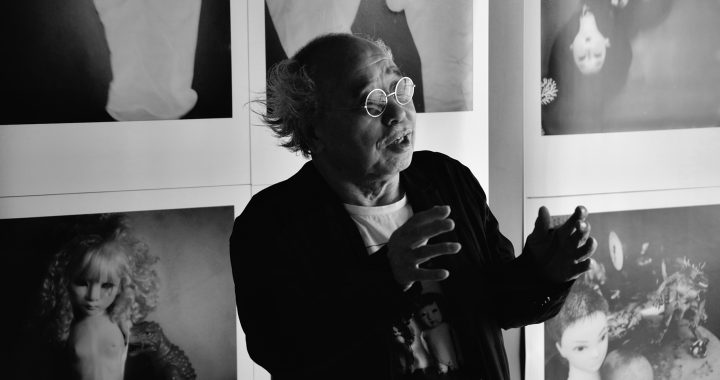

Jan Grarup (*1968) has over the course of his twentyfive-year career photographed many of recent history’s defining human rights and conflict issues. Grarup’s work reflects his belief in photojournalism’s role as an instrument of witness and memory to incite change, and the necessity of telling the stories of people who are rendered powerless to tell their own. His images of the Rwandan and Darfur genocides provide incontrovertible evidence of unthinkable human brutality, in the hope that such events will never happen or be allowed to happen again. His work, The Boys from Ramallah and The Boys from Hebron, covers both sides of the Intifada expressed through the lives of children coming of age amidst the violence. Grarup’s work takes the viewer to the limits of human despair, dignity, suffering and hope. His images are relevant to us all, because they form a chronicle of the time in which we live, but at times do not dare to recognize. Grarup has been honored with many of the most prestigious awards from the photography industry and human rights organizations, including:8 World Press Photo awards, UNICEF, W. Eugene Smith Foundation for Humanistic Photography, Oskar Barnack award, POYi and NPPA. In 2005 he was awarded with a Visa d’Or at the Visa Pour l’Image photo festival in France, for his coverage of Darfur’s refugee crisis. Jan Grarup is represented by LAIF agentur in Germany, and is based in Copenhagen – Denmark.

All photographs in the article © Jan Grarup.