There will always be someone better. Every photojournalist I have ever met says this. There will always be someone better so the work you do needs to mean something. Anyone can take good pictures, but it takes a great deal of time, work, and caring to tell a story that is deeply impactful. I truly believe this sentiment. Call me an idealist (you wouldn’t be wrong), but I think this sentiment is not only true, it holds the key to addressing some of the issues that we are facing now.

I keep thinking about long term photojournalism, whether it is staying and working in a neighborhood for an extended period of time, like Zoe Strauss, or working on a single story for years, like Stephanie Sinclair or Donna Ferrato; this is the work that I believe could help us as an industry come back to center. I also recognize that there are a number of issues with doing this kind of work and they manifest themselves in two ways; the necessity for spot news and the issue of objectivity.

We as photojournalists have a responsibility to be as objective as possible. That is what the public relies on us to do — to provide objective information so that they can make informed decisions. There has been a long debate in the photojournalism industry as to whether or not objectivity is an attainable goal. By virtue of a person taking photographs the work is naturally subjective. But I believe that a kind of objectivity (or rather, transparency) can be reached in even the most intimate of projects. As David Alan Harvey puts it, “You have to be honest about what you are doing.” Be honest about the work you are doing, your proximity to it, and the goals you have for the project. By providing the context for how you created the work, you can provide the context of the work itself.

When it comes to spot news, objectivity may be less of an issue to some degree. A photographer or videographer goes in, creates good images that tell the story, typically works with a writer, as well as an editor who organizes the work, and the whole thing is piped out to the public on the 24 hour news cycle. There is an obvious need for this work. This work is not the problem right? I think we all know the answer to this question…

Let’s go back to the 2016 election. I know! I know! I am sorry! I don’t want to think about it either, but this election actually plays a big role in the problematic trends in our industry. Back in October of 2016, it was reported that the president of CNN, Jeff Zucker, regretted giving now president Donald Trump so much airtime, stating,

“If we made any mistake last year, it’s that we probably did put too many of his campaign rallies in those early months and let them run,” Jeff Zucker said at Harvard Kennedy School, according to BuzzFeed. “Listen, because you never knew what he would say, there was an attraction to put those on the air.” Zucker, who was the president of NBC Entertainment when “The Apprentice” was first on TV said that even then Drumpf was a “publicity magnet.” “Drumpf delivered on PR, he delivered on big ratings,” Zucker said.

Pay attention to the last part of that statement, “… you never knew what he would say, there was an attraction to put those on the air.” And “big ratings.” This statement is important because it flies in the face of one of the most important aspects of journalism, providing contextualized and honest information. As I mentioned, the role of journalism industries (and I am using photojournalism, broadcast, and journalism interchangeable here) is to provide educated and contextualized information so that the public can make an informed decision. The 2016 election is a good example of how spot news failed at this tenet.

It is important to remember that context goes both ways. Sure the information was technically more ‘objective’ because it was being presented without any filter whatsoever, but was it really? The rallies Trump held were full of his campaign rhetoric and undeniable lies and airing them 100% without proper commentary allowed Trump’s own subjective position to overtake the media objectivity that needed to be in place. Reporting later that Trump’s statements were incorrect or fabricated did little good except to cover the tails of broadcasts.

In addition, Zucker mentioned that, “there was an attraction to put those on the air.” But why? That one is easy — Ratings, which = money. Trump is a ratings magnet. He gets us fired up; he makes us crazy; he is a reality TV star — plain and simple. His candidacy and presidency has single handedly spiked newspaper subscriptions.

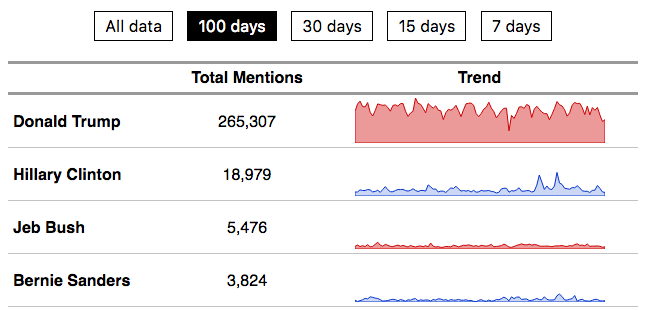

We little heard of Clinton or Sanders rallies being aired unedited in full and I expect that was because they weren’t as financially enticing as Trump rallies. In fact, all the way back in 2015 The Atlantic reported that within 100 days that number of mentions for Trump was calculated at 265,307, while Clinton had 18,979, and Sanders had as little as 3,824. This statistic little changed throughout the rest election.

From Atlantic Article

There is a little thing called the illusory truth effect, which states that if you repeat a lie enough then people start thinking it is true. But the same goes for anything else, for example, news, which gets repeated constantly. But this was broadcast news, what about other forms of journalism?

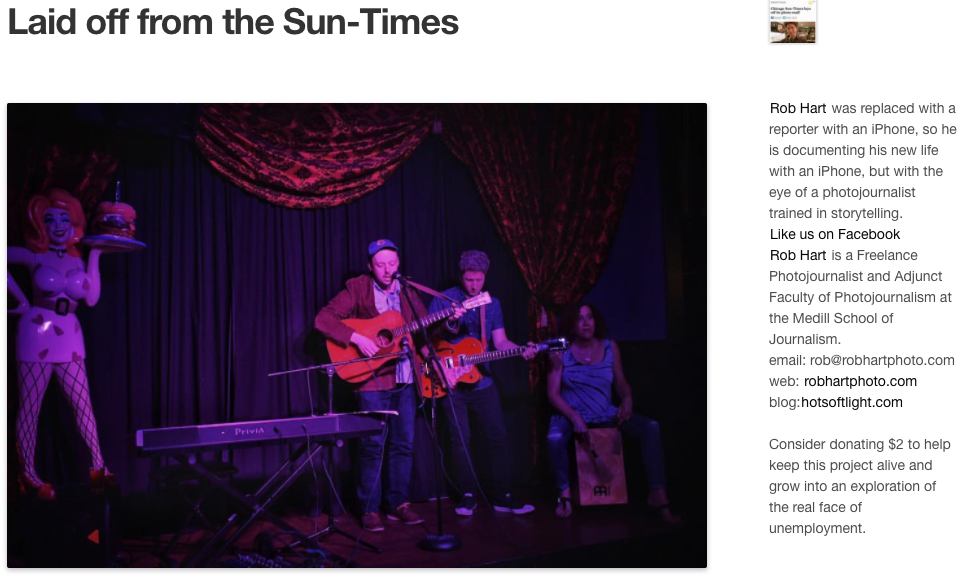

So let’s look to print journalism. Back in 2013, when I was a bright eyed and bushy tailed photojournalism student we started hearing about a trend that is all too common and expected these days; that entire photojournalism departments across the country were being laid off. Newspapers weren’t hiring, in fact they were cutting back. Rob Hart has covered his own personal forced transition to freelancer on his blog, ‘Laid off from the Sunday Times’ stating;

Rob Hart was replaced with a reporter with an iPhone, so he is documenting his new life with an iPhone, but with the eye of a photojournalist trained in storytelling.

Here is another key statement, ‘the eye of a photojournalist trained in storytelling.’ Photojournalists are trained storytellers and when we are replaced with untrained photographers who are merely required to get a quick shot and move on, the democracy of journalism is lost. The training and talent of storytelling is a method for contextualizing the news.

Just like the written form of journalism requires the skills to contextualize a story and lay it out in a manner that the audience will understand (and be interested in), so too does photojournalism require an intimate knowledge of how to shoot, as well as a visual vocabulary that we can use to convey information to our audience. The skill of a photojournalist to shoot a compelling story is a form of journalistic contextualization.

So what happens to photojournalism when the vast majority of the photographers are forced to work as freelancers? A few things; there is the possibility of photographers becoming freer to pursue their own personal projects, but there is also the undeniable truth that the field becomes more competitive and harder to survive within.

I have written, and am continuing to think about the numerous scandals and problems with photography awards today. But as I have thought about these issues, my opinion on the subject has developed. Just as the broadcast and print news organizations are struggling to understand the brave new world of photojournalism, so too are freelancers.

We are at a moment in time where photographs, and therefor photojournalism, is inherently different than what they were before. Photographs are no longer only physical analogue images; photographs are data — they have information ranging from the time, location, and day they were taken, to the F-Stop, aperture and ISO of the image. Within a camera we can see histograms of our images, as well as what part of the photo is over-exposed or the point of focus. We have an insane amount of data at our fingertips before we even transfer our images to a computer. Once in the computer, the complexity of our new image data becomes more complex. We can remove people, enlarge objects, change the color of clothing and do just about anything we want to the images we make with more ease than ever before. I am sure you know where I am starting to head with this; image manipulation.

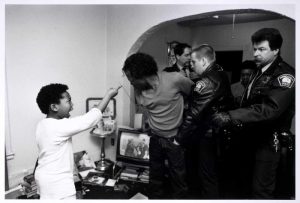

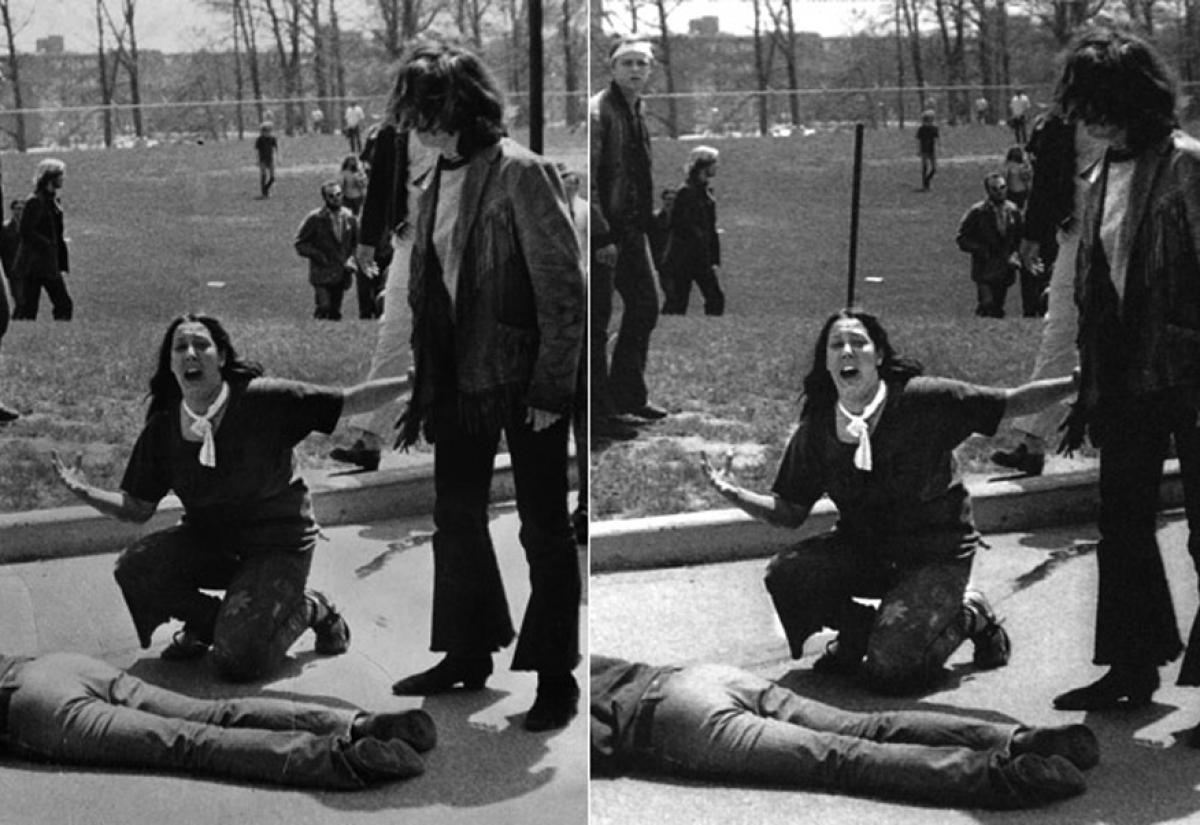

But the issues we face today are in no way restricted only to the issue of image manipulation. In fact, image manipulation has existed almost as long as photography itself has. As early as 1860 we were sticking the heads of presidents onto the bodies of politicians. Even the iconic Kent State Massacre photo had issues with image manipulation.

Kent state massacre photo manipulation.

Rather, the point that we are at now is that we, as an industry, have come to a historic intersection where our ability to easily edit and manipulate photographs (the photograph as a digital or virtual entity) has met with a fundamentally different economic system of journalism (the rise of an Internet market place i.e. a digital/virtual marketplace). We are living on a profoundly different plane of existence as an industry.

Now before you even think it; I am far from damning the Internet. Rather, I acknowledge the benefits and challenges that our new system creates for us. For example, the Internet has supplied me with the ability to discuss these issues with a wider audience, something I may never have had the opportunity to do through traditional structures. In effect, I am freer to do the work I want to do; yet, I am met with the lack of financial support and reimbursement for work done.

We do not yet know how to operate as an industry in this world and the traditional structures and organizations of the photojournalism industry are buckling under the pressure.

Editor and photojournalist James Estrin has said;

I wish I had the absolute answer to how we will make a living on the web. I think that there are extraordinary tools for photojournalists on the web. In a sense it’s almost the golden era for photographers; the ability for them to have their work seen; the ability to be the full author and storyteller in using multimedia, but at the same time it’s disrupted the economic models that we’ve worked under and it is a questions as to how the photographer could make a living and whether the current large media companies will be re-transitioned. There’s less money. It makes for an exciting time; more innovation. But I think of this fairly often. I wonder what will happen in 10 years. What room is there for me to do the work that’s important to me, but also be able to make a living?

New photojournalists invest huge sums of our own personal money to tell stories and are frequently met with a traditional system that doesn’t necessarily welcome us (despite their best intentions), and a new system that cannot provide financial security. This is being met with a second blow to aspiring photojournalists in the US with the college debt crisis (which as much as I would like to, I am not going to get into for this article). Like it or not, photojournalists are getting very little love these days. As Alain de Botton puts it;

The problem with photojournalism is there is ever less of it that news organizations will pay for reliably… philosophers are at the top of the league [for being the most disliked], but right below them are photojournalists. No one loves them… great material is not recognized. It’s very, very important to have good pictures. That helps a story to get across.

But the fact of the matter is that this is an issue that has been creeping up on us for some time. As Fred Ritchin wrote in Ken Light’s book, Witness in our Time, in 2000;

One day, or course, we will wake up and say, “Oh my god, how did this happen to us? How did we lose so many jobs? How did journalism become so irrelevant? How come we have increasingly autocratic governments?”

Sound familiar?

And so, we are at the privileged point in history where we as an industry, as a community get the opportunity to act. Honestly, we don’t have much of a choice at this point.

I would argue that the current options at hand on this Internet are lacking and do not provide sufficient compensation or support for photojournalists, rather, they require new photojournalists to offer their work for free, pay-to-participate or compensate very little. Our industry is stuck looking back to old form while trying to exist on the Internet, rather than looking forward and trying to innovate.

Does this mean that these organizations are maliciously targeting up and coming photojournalists for their own financial means? No. They are simply trying to cover their bottom line. These organizations are also trying to survive. But if the current financial set up is a pay-to-play system then the issues we are facing now are not surprising. If this continues we are at risk of delegitimizing the entire industry. Think about it, if the system is play-to-play then only those who can afford to pay can play. This does nothing to promote the democracy of photojournalism and its ability to serve a common social good, rather it creates a plutocratic form of journalism.

When I asked James Colton about how editors are reflecting on the recent issues at hand with Datta, McCurry, and the World Press he responded;

Good editors are calling out these offenses, be it Datta or McCurry. It doesn’t matter if you are a master or a journeyman, there are certain lines you just don’t cross. Part of the problem we are facing today, is that there are less and less editors, as well as fact checkers and personnel in general. Organizations are cutting staff to save money to the detriment of vetting. We lose institutional history when journalism veterans are laid off and then not replaced. The remaining staff are taxed way too much with added responsibilities and quite often things fall through the cracks that would have been caught before especially by someone with a seasoned eye.

So this issue is spread across the entire spectrum of the photojournalism industry. It is easy for me to believe that the big bad editors in the big bad companies are just out to make money and preserve outdated forms of photojournalism dissemination, but that is in no way true. They too are facing the same issues that photographers are facing.

In fact, since I started writing, a number of photographers, editors and agencies have approached me and said, “We know! It is a huge problem and we want to solve it too!” So I really do believe that we are all committed to addressing this issue, the trick is figuring out how.

When scandals, especially a seemingly never-ending stream of scandals, come to light within our industry, I think it is a harbinger for a larger problem; a harbinger that we are not just feeding our ego through our work, but that we are desperate as an industry. We are desperate for support and acknowledgement; in the age of ‘fake news’ we are being required to prove ourselves again and again — at times to people who little deserve it and use the ‘fake news’ title as more of a propaganda scheme than a legitimate point of critique.

This puts us at risk of stagnation, or worst, back tracking from previous lessons learned. When photojournalists ask, how can I win awards, how can I get the next grant, how do I become the next big photography legend; when news outlets ask how can we get the most clicks, we have to check ourselves because these are the wrong questions.

In Ken Light’s book, Witness in our Time, Donna Ferrato mentions in her chapter, ‘Living with the Enemy: Domestic Violence’ that,

I get sad when photographers — experienced or amateurs — come to me and say, “How can I get my name out there? How can I get people to respect me? How can I get the assignments?”

They ask, “What am I going to get?”

My feeling is not what you’re going to get. More like what are you going to give? What are you going to learn? There is so much to learn out there with a camera. It gives up power for educating ourselves and for educating others. We have to be patient, try to learn as much as we can until there comes a point where we have something to share with other people. And that doesn’t come for a long time.

I think we are at a historical point of refrain, like the chorus in a song. Because of the recent scandals in the industry, we yet again are being forced to ask ourselves, what is the role and purpose of photojournalism in society? I have always seen the role of photojournalism in society is to serve the common good. This is not a radical idea by any means. In fact, I believe the role of most careers is to serve the common good. The concept of one’s legacy is built on this idea.

And that brings me back to my initial point; in-depth, and heartfelt photojournalism and documentary will be the saving grace of the problems within our industry, but we have to figure out a better way to support and prioritize these stories.

We already know that to insure that our role to serve the common good is fulfilled all pertinent entities, be they photographer, editor, fact checker or audience, must check and balance each other as work is produced, distributed and awarded. However, because the industry is at such a metamorphosis — as the economics of our work changes — the traditional checks and balances of this system feel a bit off kilter these days.

In addition, it is hard to nail down just how we maintain these checks and balances across the various platforms of photojournalism. Not all journalism is created equal. The work of CNN or MSNBC (or… eh, Fox News) is not equal to the work of Magnum and VII photographers (not by a long shot, frankly). There is undoubtedly a hierarchy of work. Broadcast has different goals than print; local news has different goals than national or international news, etc. There are more intellectual forms of journalism as well as more hedonistic.

The issue of photojournalism’s metamorphosis is an extremely difficult issue to address together. In fact, it is hard to address this issue within just our respective photojournalism sections. I do know one thing; it is important that we keep these conversations going. It is even more important that we make these conversations public. It will do us little good to keep the conversation in the photo ghetto. Our audience needs to know about and have a voice in how our industry changes. We are starting this conversation. More and more people are commenting on the lack of diversity in the industry; in the ever-analyzed issue of photo manipulation; in how we can develop financial support systems for our work, and much more. We can always do more. I am also continuing to think about how I can push this conversation myself. How can I move the industry forward?

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” – Martin Luther King

Photo on the right – © Roya Ann Miller.