Fatemeh Behboudi focuses on capturing stories of her country. Iran is stigmatised by the iraque-iranian war (1980-1988), which left deep scarfs in lifes and souls of iranian people. Her series about mothers waiting on any message about their missing sons has been awarded at World Press Photo 2015. She has been interviewed for dofoto and spoke about her life, creation and her way to journalism and documentary photography.

You were born and live in Iran. How was your childhood?

Like many other people, I had a strange and hard childhood. I was born in 1985 in the midst of Iran-Iraq war. In a year that my country was involved in the biggest classic war of the century and the atmosphere of my life was interwoven with war issues.

During childhood, I went with my father to the streets to welcome the return of bodies of martyrs of war or we played games with themes of war, martyrs and tanks in the kindergarten and drew paintings of missiles and Iraq’s airstrikes. Also, I cannot forget the movies and the sound of sirens played for the Iranian people during those years. The Iranian people still spoke about Saddam Hussein and his crimes a few years ago and it was always interesting for me that how such a person like Saddam cannot be forgotten for years.

And I was born and grown up in such a stressful atmosphere.

You studied at Art Center of Jihad in university of Tehran. Why did you choose photography? What was the impulse and why social documentary and journalism?

My father was once a photography student and I chose this field using his guiding but the most important reason for me to choose photography was the death of my best friend. She loved one of my photos before death and told me “You have taken a photo of the tree’s spirit and I believe that you will one day become a great photographer.” That was the last thing she said to me before she died. Her last words was like a miracle for me, a light in the darkness and were the most important motivation for me to choose photography.

I started the job with photojournalism first but two events persuaded me to do documentaries. First I was interested in taking photos of the politicians but people’s protest at the results of the presidential elections in 2009 and the restrictions I had as a female photographer in the Iranian media made me more interested in the documentary photography and approaching people.

You have worked in several agencies. Being a woman and working as a journalist. Are there many female photographers in Iran working for news agencies?

There are not so many female photographers active in Iran which is maybe related to the difficult and unequal conditions of work in Iran’s media atmosphere. But at present and in the past two or three years, the number of female photographers has increased in the documentary photography and I believe that we will witness their flourishing in the near future.

How is the style of work in IRNA agency you currently work for? What is your main photo topic there? Do you have a possibility to work on your personal projects?

I work in this news agency as freelance photographer. I cover the press conferences and sometimes carry out documentary projects.

I have not yet found a proper place for my personal projects. Of course, I have had some proposals but given the abundant restrictions here, I prefer not to take a risk and I work for myself at present.

You are focused on war, but not in a conflict itself, but on its consequences i.e. the series Mothers of Patience. Why did you choose the theme of mothers or martyrs? Is it personal?

I have felt that there are many issues to work on “after war” field in the world and not many photographers have worked on them and I have seen these issues not only in Iran but also in the world. By choosing these stories, I tried to display a humanitarian story which has involved all nations as wars have happened for centuries and many families have been victimized by the warmongers. During the wars, the religion, tribe or race is not important. The important thing is that all are killed under the name of war without any winner among them.

The story of Mothers of Patience is also one of these stories. I started my first news project on the funeral ceremony of missing Iranian martyrs in 2007 and gradually, I asked questions from myself about people and the society’s need to it. My participation in the World Press master class in 2013 motivated me to start the project.

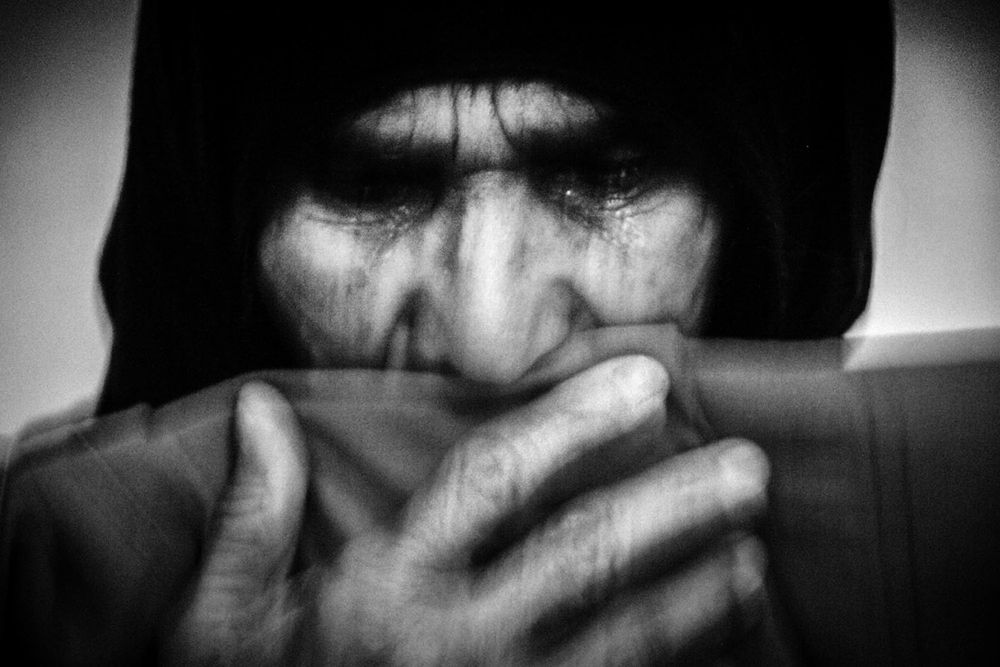

During the project, I many times visited the graves of the martyrs in Tehran and understood the difference between the life of mothers of those martyrs whose bodies have not yet been found and the families who have received the bodies of their martyrs and buried them in Tehran cemetery.

It was interesting to me to show the difference between the lives of these two groups of war victims.

Your work is being recognized and featured globally. For example you won Honorable mention in World Press Photo, Contemporary issues category. How did you feel? Did it change it your life in some way?

I can say that this even left a deep effect on Iran’s photography society and I am happy about it. But this didn’t have a positive effect on my life and I should sincerely say that it showed me hard days and sometimes I regretted winning the World Press Award. The Award taught me that you should know in which society you have won it. In the male dominated society of Iran, it wasn’t a pleasant event for my colleagues and I lost good job opportunities for it.

There is death penalty execution still in place in Iran. You have photographed one. What was your feeling about that?

I have taken photos of 5 execution events in 4 cities of Iran; a bitter experience which made me closer to the realities of my society. It was surprising to me that how excited people are present in the execution ceremony of a human being and even the children can easily watch it and it wasn’t important to anyone to know how much this event can negatively affect his/her life and children. It was a bitter and disgusting feeling for me and I tried to remind the bitterness of this event in the Iranian society by displaying the project. Fortunately, public execution rarely occurs in Iran today and I have not heard of it for a long time.

How do you see European or US press photographers in the field with their effort to get closer? Do you help them or do you give advice if needed?

The US and European photographers are very experienced and I think that I should learn more from them. But if my photography and view can help, I will certainly help them.

Taking pictures of sorrow, pain and human lost is psychically demanding. How do you deal with it?

Photography has been my most important master. It taught me that I should experience different events and train myself to become a good photographer. I experienced incidents like flood, earthquake, execution, etc. The events which can involve my feelings and I can manage my feelings with them to take photos of more influential events in bigger projects in the future.

While working on the Mothers of Patience project, I never involved my feelings but I allowed myself to show my feelings on the issue in my photos and speak with the audience about the event through them. But after work, I watched the photos during day and thought about the subjects which had influenced me and cried for a long time.

Life in Iran is strongly connected with traditions, faith and religion. Are people in your country opened to be photographed? How do you gain their trust?

I think that everything depends on the type of my story. About what my story is speaking and how much I can approach people’s personal atmosphere? Religion and tradition are two powerful instruments which influence the Iranian people’s life today and entering these atmospheres can be easy or very difficult sometimes. Fortunately, the Iranian people are always hospitable and they warmly welcome the photographers and documentary makers. But one cannot enter their personal atmosphere easily without knowing them.

I am always sincere with people and speak with them about the photos and the influence they leave in the society and this has many times helped me.

What is the current situation of documentary photography in Iran? Is it well accepted?

I think that documentary photography is still young in Iran and it hasn’t been able yet to find its proper place. Therefore, it is growing slowly given the lack of social supports.

The reason is that the Iranian people have not yet understood the power of this media. But there are many young photographers who have started documentary photography and we will certainly witness a big event in Iran’s documentary photography in the next few years.

The migration. Would it be interesting for you to visit the refugee’s community in Europe and to photograph them?

Yes. 100%. I like to live with the refugees a while to become familiar with another part of the war and its rough face. It is important to me always to be a part of an event, feel it closely to be able to do an effective job. I hope to have the opportunity for such photography one day.

What is for you the most emotional picture/series and the story behind you have taken?

It is a photo of Mothers of Patience project. The photo of mother of a martyr who has slept under a tree which was planted by her son during the war time and it is the only memory for his mother. The mother has lived under the tree for the past 30 years and is waiting for the return of her son’s body and this image is the most impressive photo for me.

Which series are you currently working on?

At present, I have no decision to start my new project. Two issues of “the young Iranian immigrants” and “the impacts of chemical bombs” are the projects that I will work on one of them soon.

What are your plans for the future? Do you have a “dream” project?

I don’t know exactly to what country I will go in the future or I will decide to remain in Iran; but I am interested to attain new experiences in photography. I hope to work on impressive projects in Africa one day.

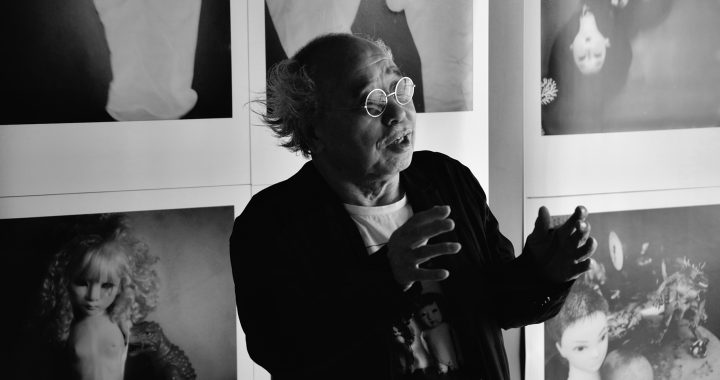

Fatemeh Behboudi (*1985) was born in Tehran, Iran. She studied photography and after graduating from Art Center of Jihad at University of Tehran she has worked for several Iranian news services including the Iranian Quran News Agency (IQNA), student news agency Pana, Bornanews and Mehr (MNA). Besides other recognitions, in 2015 she gained Honorable Mention prize in Contemporary Issues category at World Press Photo competition with series called Mothers of Patience about the Iran-Iraq War the one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century. She currently works for Iranian news agency (IRNA) and is based in Tehran.

© Copyright reserved. All photographs © Fatemeh Behboudi.

Mothers of patience – photo essay by Fatemeh Behboudi