Hanna Jarzabek is very talented and perceptive author who mainly deals with communities outside of the majority. As an example of her work, I have chosen a long-term work with lesbian couples living in Poland, which is still characterized by a traditional society in which the issue of homosexual people and their rights often shows strong homophobic reactions.

Greetings Hannah, how did you get to Spain from Poland and what did this country bring to you about photography?

I left Poland 23 years ago and at the first I went to Switzerland, where I spend almost 13 years. I studied Political Science there and at some point, while doing university research on Palestine I started to photograph. One Swiss photographer saw my images from Gaza Strip and encouraged me to dedicate more time to photography. So this is how it really started. When I moved to Spain in 2008, I decided to start my first serious documentary project – „Lesbians & much more“.

What did the study of political science and cooperation with OSN in photographic projects mean to you?

A lot! I think this gave me a background on how to focus and prepare subjects, how to investigate topics and how to document everything I hear and watch. It really helped me develop a critical point of view, which I think is very important in documentary photography.

When it comes to working for United Nation, well, it showed me how much time and energy can be lost in big organizations and convinced me I need another tool to speak and act on what I see around. Photography gave me this option.

Do you feel free now as an independent photojournalist and teacher?

Well it all depends on how you define freedom. I feel free because I chose my subjects myself, I decide myself how to elaborate them, what people to contact, what focus I want to chose etc. In general also I have control on what is published, especially when it comes to text and information. Only few times it happened to me that some redaction added or change something small. So in general I consider myself very lucky to be able to work like this. But, if we start to speak about economical side of the profession, it is definitely an another issue.

For what reason do you choose very sensitive topics dealing with social discrimination?

I think it comes with my personality. I just cannot stand when people are discriminated for any reason: skin color, religion, gender, orientation or even economic situation. It is really something that produces my profound disagreement, repulsion even. I just don’t understand how is it possible that one human can discriminate another – I mean, I know it exists, but I just don’t understand how is it possible on human level. So I want to speak about this, I need to show it because, on one hand I hope in this way at least somebody will feel encourage to revise his or her position, to think over things. On the other hand, I think it is also somehow my “coping strategy” to be able to live in those societies we build. Yes, I think I implicate myself very much in what I do.

Recently, you have been photographing in Russia, why the country attracts you?

No it was not Russia, it was in Transnistria – the separatist part of Moldavia. It is a de facto state that is not recognized by International Community and in general people there are very pro-Russian. My focus there was more about it how much the lack of recognition impacts everyday life of the population. Something like looking for the answer to the question – Is it really worth and realistic to separate?

But, coming from Poland, it was also a very interesting experience for me. I spoke with people who until now are very proud of the Red Army and believe strongly that USSR saved the world from fascism. At the personal level – sometimes it was difficult, but those kind of experiences show me, once again, there is never only one truth and I think it is at least worth to listen to someone’s story before making my final opinion.

What was obvious for me is that, as in many other places, the propaganda is very strong there and right now in Transnistria, Putin is presented as a hero and the best politician to take care of, what they consider “Russian world”. Of course it is a very sensitive topic, but when one person once told me: “The Occidental World has Trump, should I really chose Trump over Putin?” – I honestly did not know what to answer to him.

How do you perceive the strong documentary scene in Poland?

As I said I left Poland 23 years ago and for a long time, and because of the personal reasons, I was not visiting this country. Only recently I started to build back my own relationship with the country I come from. So there is many things I’m still discovering and what I can say is that Poland changed a lot throughout those last 30 years, which of course had an impact on documentary scene. I think there is a lot of incredible and talented people who are not afraid to touch sensitive topics. For example Tomasz Siekielski, who did incredible, strong, touching and very well documented movie about pedophilia in the Polish Catholic Church. I feel happy and proud such people exist there.

How did you get to the Lesbians topic, that we publish in our magazine?

In December 2008 I went to Poland after a quite long absence. I had been living in Geneva for about 13 years and I back than had just moved to Barcelona. Both – Geneva and Barcelona – are very open (or at least had been) cities, where homosexuality in general is perceived as absolutely normal option for life. So when I arrived in Poland and heard and saw very strong homophobic behaviors, I was shocked. It was even stronger because all this homophobia was very institutionalized. I always say that homophobic people, unfortunately, can be found anywhere. Another question is when the country, the government, public institutions and law are homophobic. And it was the case in Poland in 2008. So I decided, that as a polish I have to do something about it and I started to investigate and look for people who would accept to participate in the project. Unfortunately now, 10 years later, all this institutionalized homophobia is back.

Why did you choose a black-and-white visual testimony, when you mainly work with color?

Back than, I was working with an analogical camera and using black and white films. I really love working like that! And I do think color is a tool and with some subjects is necessary (for example when I did a project about Transsexual women I knew it had to be in color). But sometimes color can withdraw attention away from what is really important.

What was it like to watch the intimate world of two women when you are a sensitive woman yourself?

I prefer to refer to sensitive human beings. I’m more and more convinced we would be much happier without this binary division between man and woman. So I would rather say how I felt watching the intimate life of two human beings who love each other. Well, as in any other similar situation: when I see love and respect people give each other I simply feel grateful they exist. And in this case, I felt even more grateful they accepted to show it to me and share it with me. I also felt rage and anger they cannot live normally like anybody else. And I still feel it.

You photographed 12 different couples in Krakow, Warsaw and Gdansk. Why exactly in these cities?

I did not choose those cities. From those places some couples answered my announcements and my searching for participants. Of course it is because in big cities it is easier for people to come out and show their face. I would love to document life of somebody from a small village, but back than the most important for me was to show those people exist and show how they live. I really don’t like this world “normal” – because who decides what is normal and what is not? – but for the sake of the conversation sometimes we have to use worlds we do not really agree with or like. So I’ll do it now: I wanted to show the “normal” life of lesbians couples in Poland so those who are against would question their positions, would see there is nothing to be afraid off , nothing dangerous nor deviant, just simply love.

How do women couples perceive your output in exhibitions and possible publications?

I think in general they were happy they participated. With some of them I have contact until now and with some I have even developed strong friendship that continues. I think it is also because with many I spend long, like three months, previous period of talking and knowing each other. It was done in general by skype because I was living in Spain, but when I arrived with my camera in their lives, they new what to expect, at least more or less.

What does intimacy in documentary photography mean to you?

It depends on the subject. Not every subject needs this intimate approach. But I think with subjects like this, it is really important to develop intimate link with the person. I think the most important in it is respect and trust; on both sides. I need to respect and trust the person I photograph and I need to know she /he feels the same about me. Otherwise it simply does not work.

How does a young generation seem to be inclined to documentary photography for you as a teacher?

Uff. It is a topic for another interview [smile]. In general I think people want to speak about what is going on, they want to relate stories, look for stories, they are curious and full of energy. The biggest problem I see is time. Everything goes so fast now that people are in hurry to do things and sometimes they forget that it is a process. I don’t refer only to the time spend on each project. I also think about this that each project teaches me something new about myself also; something I can use while preparing the next project. That is why I see it as a process, which demands time and the capacity to be open and critical with myself.

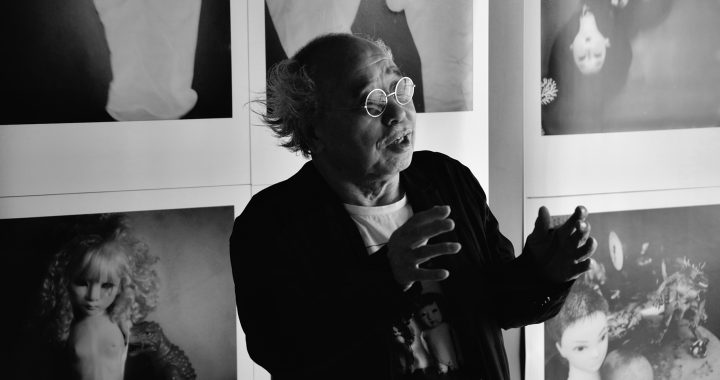

Hanna Jarzabek (*1976) was born in Poland. She finished a Master degree in Political Science and worked on refugee reports for UN agencies such as UNRWA and UNCTA. She developed her passion for photography while travelling (the Gaza Strip, Iran, Philippines). Since 2008 she is based in Spain where she works as a freelance photojournalist, combining her personal projects with the teaching of photography. She has published in BuzzFeed News, XL Semanal, L’Obs, Equal Times, 5W magazine, Interviú, El Periódico de Cataluña, 7k magazine, Gazeta Wyborcza and Polityka among others. Her projects address discrimination and societal dysfunctions in western society. She also works on youth radicalization and the raise of right-wing movements in Europe. Lately she has started to investigate the construction of national identity in post-Soviet regions in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. She has won different awards, such as the Third Prize in POY Latam 2015 (Mexico); she has been awarded with the Grant Programa Crisálidas Signo Editores Grant 2019 (Spain), with a Helge Humelvoll Scholarship to participate in the 69th Missouri Photo Workshop (USA 2017) and with the “Photojournalism Grant 2015” (GrisArt International School of Photography, Barcelona), among others. Finalist of the Grand Press Photo 2019 and 2012 in Poland and of the 19th FotoPres la Ciaxa (2013); she was also nominated in 2018 and 2017 Edition of Photography Magazine Grant (London). She has participated in festivals such as PhotOn 2019 and 2018 (Spain), Imaginaria 2019 (Spain), UCL Festival of Culture in London (2017), FOTONOVIEMBRE Tenerife (2015) and the VIII Biennal de Xavier Miserachs (2014) among others.