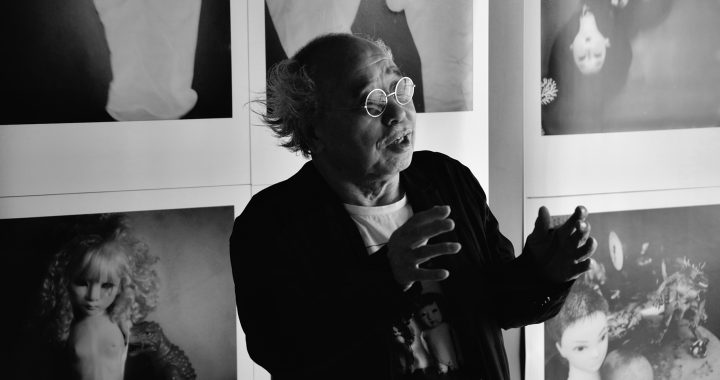

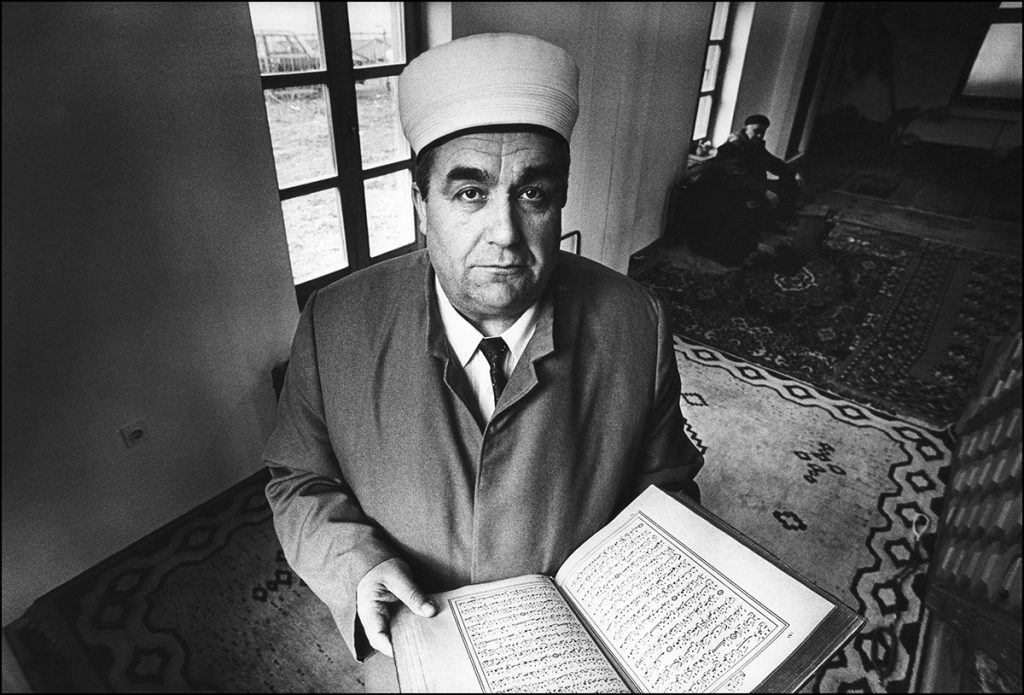

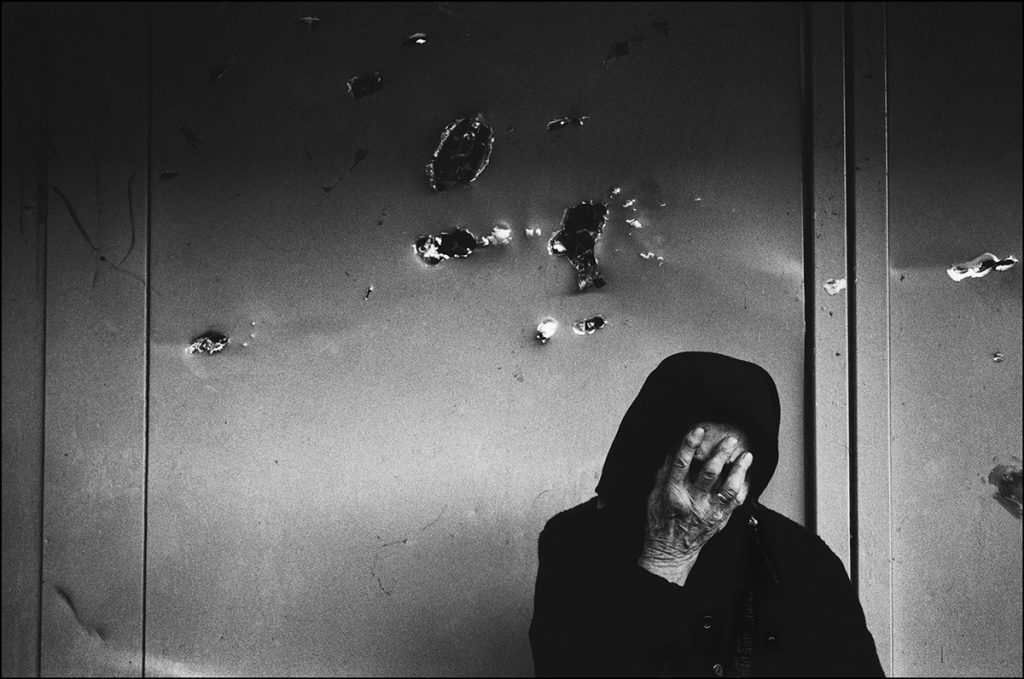

While Judah Passow’s photography shows us a world full of raw emotions, relentless violence and pointless suffering, it also reveals his discovery of pockets of faith in human resilience. A four-time World Press Photo award winner, his work combines photojournalism with the philosophy of humanism. His personal experience with combat informs his work in conflict zones to produce photographs which draw attention to the futility of war. Born in Israel, raised in the United States, and living in London, his own shifting cultural history drives him to explore other people’s complex issues of identity. In our interview with him, he explains why contemporary documentary photography needs to reclaim its ethical purpose.

What does photography mean to you and why did you choose it?

Photography is a tool for exploring ideas and engaging in a conversation about them with other people. I don’t think I chose it. I think it chose me.

Your professional career as a photographer started in 1974 at the Jerusalem Post. Do you remember your first assignment?

I had just launched myself as a free-lance photographer and was looking for work. One of my friends – a freelance writer who contributed regularly to the Jerusalem Post – rang me one morning to ask if I was interested in shooting for a story she had been commissioned to do. Her editor said the picture desk didn’t have any photographers available, and instructed her to find one and have them put the film in a taxi and send it in to the paper when they finished the job.

I shot the story (it was about a young American immigrant in Israel who was running a rehabilitation program for severely physically disabled children) but instead of sending the undeveloped film into the paper, I went back to my darkroom and made a set of black and white prints which I sent in by taxi. Two days later, the story ran as the lead in the Feature section of the paper, with a single image used a page wide and half a page deep. A couple of days after that, a letter came from the picture editor with a check for the assignment and an offer of a staff job.

As a photographer you have covered several conflicts since then, i.e. Afghanistan, Lebanon, Bosnia. Your photographs are almost entirely about the suffering of ordinary people. How do you establish intimacy with them?

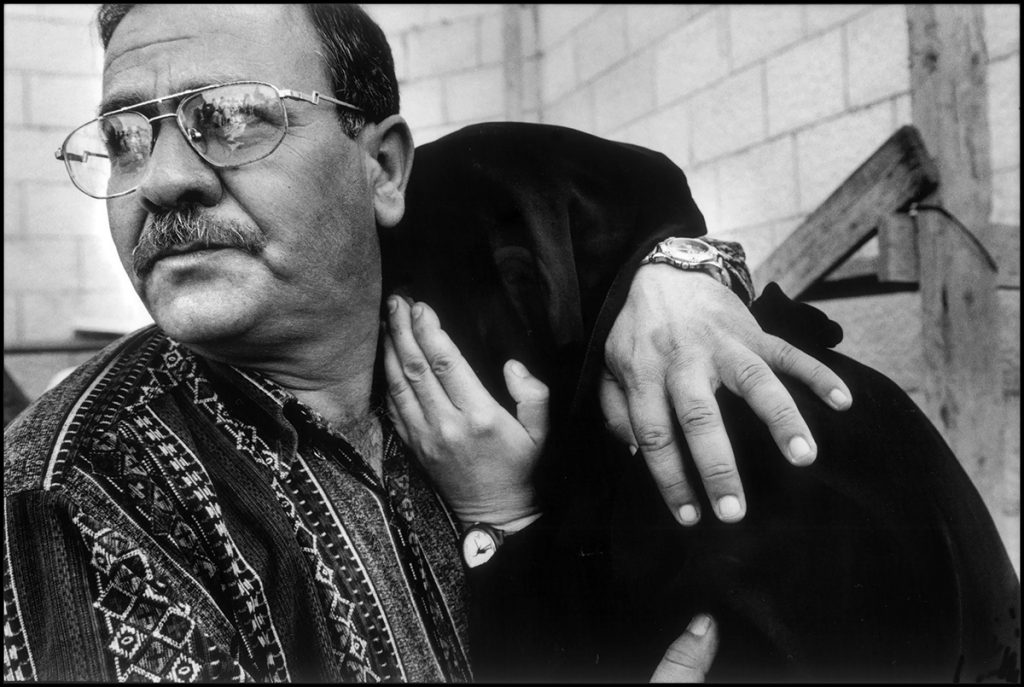

By spending time with them. The kind of intimacy that gives a photograph its real power can only come once a certain level of trust has been developed between the photographer and the people being photographed. That trust is purely a function of the amount of time you spend getting to know each other. This process can take days or even weeks, depending on the complexity of the story. But once that trust has been established, you find that people take you into their confidence and into their lives, and that’s where the photographs are.

Did it affect you emotionally?

Of course. These experiences can’t possibly leave you unaffected. Your emotional response to a situation is an absolutely essential element in a photograph of any importance. Bruce Davidson once observed about his own work that “My pictures aren’t so much about telling a story, as they are about my relationship to the story”.

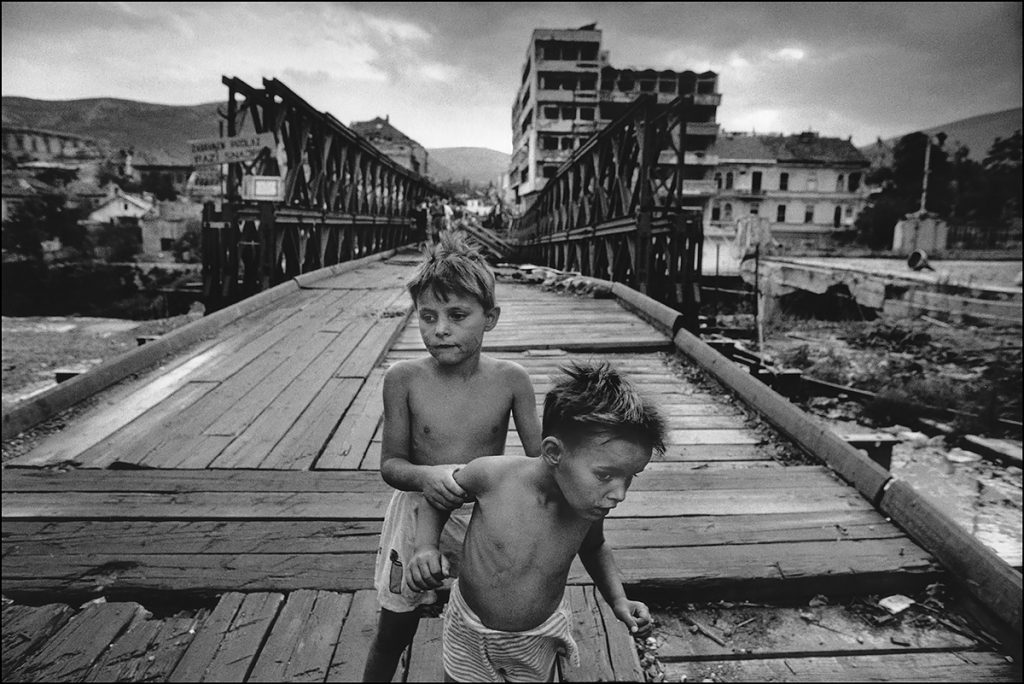

Your series from Bosnia is, in my opinion, very strong because of the sensitive way in which it deals with the subject. You called it Harvest of Tears. How do you remember the time you spent there? Did you sense the futility of this conflict?

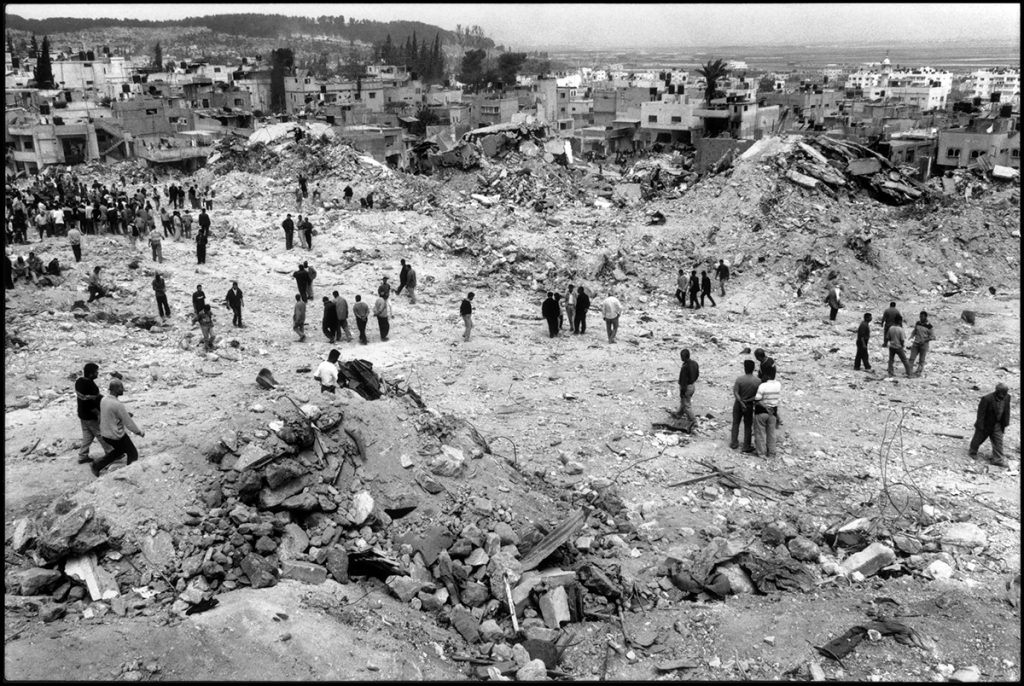

Covering Bosnia was an eye-opener. I had, by that time, photographed conflicts in Northern Ireland, Israel, Lebanon, Afghanistan, and southern Africa. But Bosnia was different. This was a complex, evil, ethnically-driven war in the middle of Europe, led by barbarians on three sides who weren’t the least bit interested in what the rest of the continent had long ago accepted – that diplomacy is a fundamental principal driving civilized society. There are some conflicts which can be argued are existentially necessary – the Second World War, for example, or the 1973 Middle East war. But by and large, all armed conflicts are ultimately futile. In the end, they simply replace one set of problems with another, and resolve nothing. Bosnia stands as a classic example of this kind of stupidity.

You fought on the front line in the Yom Kippur War (1973) and were one of the first six Israeli soldiers to cross the Suez Canal. Not many war photographers have this experience. Do you consider it an advantage when covering conflicts?

Absolutely. The army taught me several skills which are an invaluable asset in conflict photography. These skills range from threat assessment and survival in hostile environments to time management, planning and organizational methods. Photographing in a war zone requires clarity of thinking and personal discipline in order to cope with the peculiar demands of the job, which is to produce a compelling set of photographs under very dangerous conditions. A lot of photographers try to do this kind of work, thinking it’s a good way to kick-start a career. Far too many of them aren’t properly prepared for it. Some of them pay a very heavy price because of that.

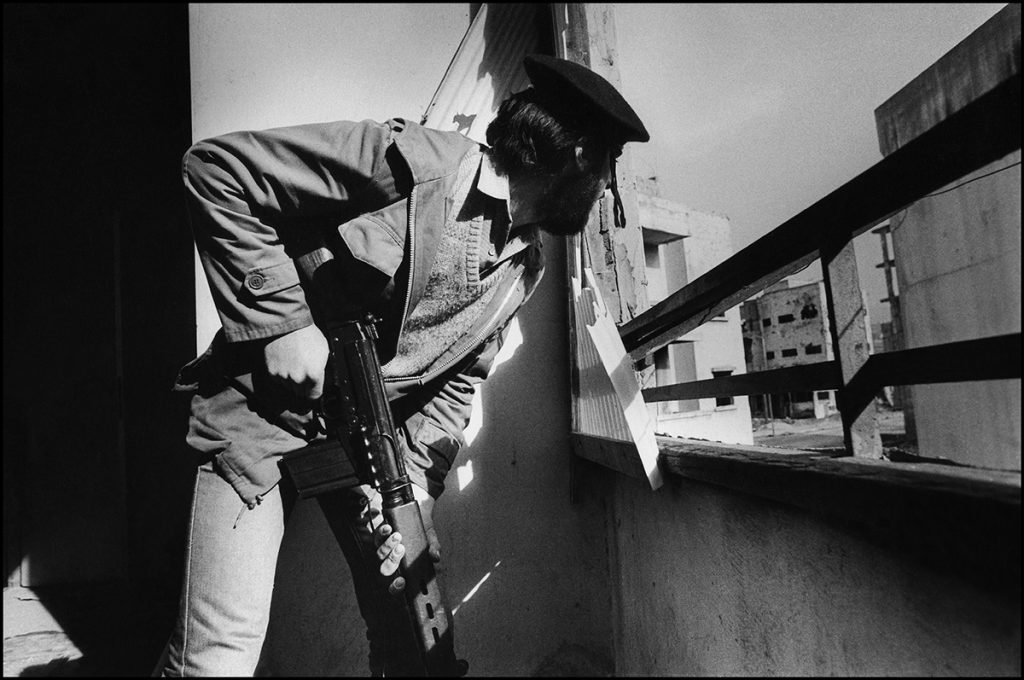

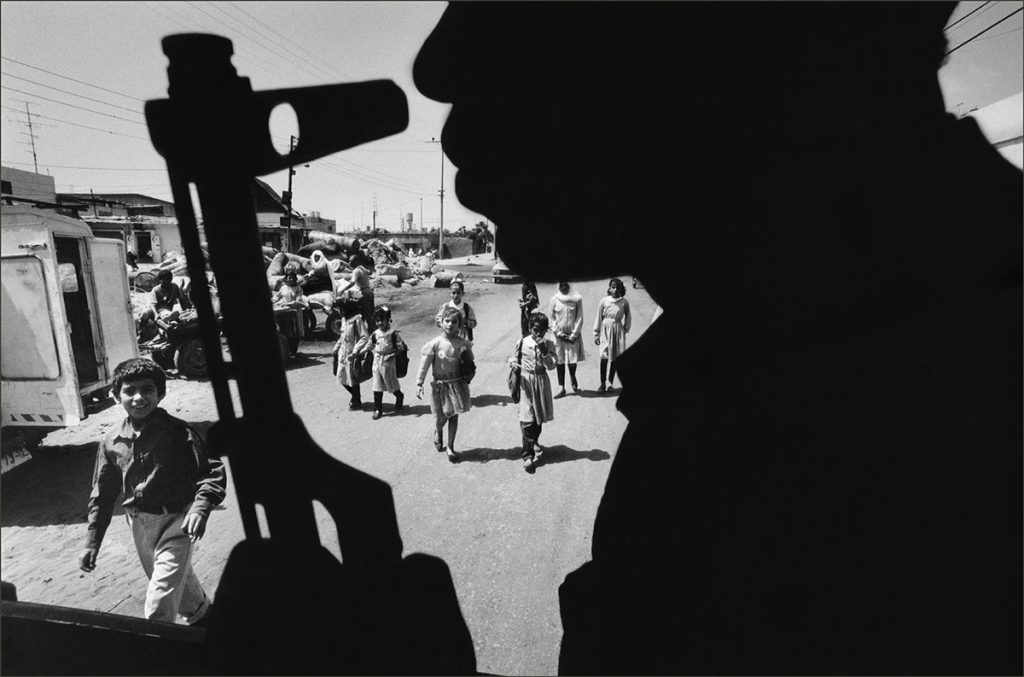

You spent three years (1982-1985) traveling back and forth between England and Lebanon photographing the Israeli invasion and the fighting that followed it for The Observer. What was your personal motivation to do that?

I saw the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon as an aspect of the wider Israeli-Palestinian conflict which I had started photographing in 1974. All of my work until then had been in Gaza, the West Bank and the Golan Heights, looking at the conflict from inside the Palestinian’s world of the occupied territories. I felt it was important for me, as an Israeli, to understand what the consequences of this conflict were for people who history seemed to be treating with indifference. Photographing the Lebanese invasion and the three years of fighting that followed was a logical progression from all of my work that preceded it. My intention then, as it remains now, was to take photographs which make it clear to both sides that no one has a monopoly on suffering, that this conflict has reached a point where all it is achieving is inflicting pain on everyone involved.

You won four prizes at World Press Photo. Did this contest help you to get global recognition?

It’s hard to know, really. My instinct tells me that prizes are great for the ego but really don’t mean much more than that. Picture editors don’t keep a list of prize winners next to the phone on their desk when they’re looking for a photographer. The quality of your work and your integrity as an individual are what get you recognized.

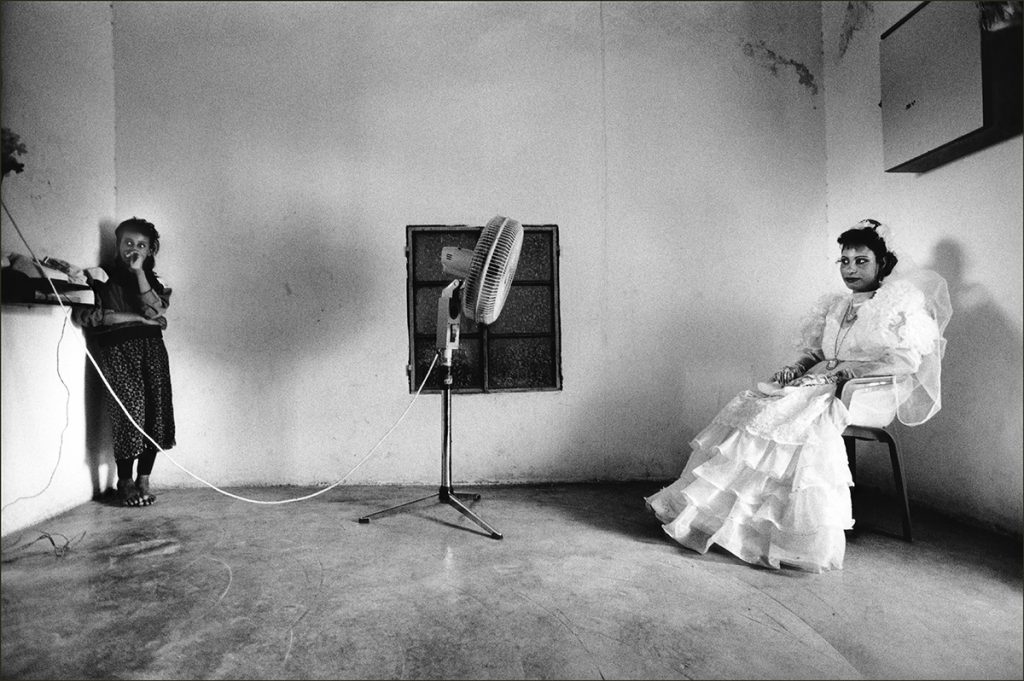

Shattered Dreams, your book about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, was published in 2008. It is a personal journey through this conflict over the past twenty-five years. Photographs in the book are not laid out chronologically. On what, then, are the juxtapositions based?

It makes no difference how you sequence the images – chronologically or randomly, the message of the conflict’s relentless tragedy doesn’t change. The juxtapositions created by the layout of the photographs are intended to convey a sense of this futility. This is a place where the young are robbed of their childhood and the elderly stripped of their dignity. The people here glorify their past, curse their present, and have difficulty imagining a future.

What do you think is the main difference between the photojournalistic and the documentary approach?

My understanding has always been that a photojournalist is, by definition, a documentary photographer, and that the two terms are actually interchangeable. Philip Graham, the late publisher of the Washington Post, famously said that “Journalism is the rough draft of history”. The photojournalist produces the visual documentation for that rough draft. I suspect the distinction between these two terms is just a contemporary sematic game invented by academics to justify the expansion of their curricular empires. What I find irritating is that this artificial distinction has been allowed to morph into a legitimized photography genre of its own, hijacking the notion of integrity implicit in a “documentary”, and appropriating the term to describe work that is largely fictional, obsessively self-referential, and technically manipulated. It’s an Orwellian concept – documentary photography today means the exact opposite of what it was originally intended to mean: the photography of hard, stark, unvarnished reality. Which, to bring us full circle here, is precisely what photojournalism does.

What is the main difference between the work of a photojournalist/documentary photographer in 20th and 21st century?

I think photojournalists in the 20th century had a level of commitment to examine society and question many of it’s assumptions that photojournalists in the 21st century generally lack. Part of that has to do with the change of editorial culture in the newspaper and magazine industry, which used to provide both the money and the audience for photographers whose work looked at the world in this critical way. The vacuum created by that change at the beginning of the new century was filled by photographers who’s work reflected the industry’s new preoccupation with consumerism and entertainment. The intellectual anger that drove the work of the 20th century photojournalists has been replaced by intellectual complacency in the 21st century.

You were a consultant to the Soros Foundation’s Open Society Institute, training photojournalists in the former Eastern Europe. What did you teach them? Do you still work as a lecturer?

Photography in the old East was an instrument of the state and regarded by most people with suspicion. It was used primarily as a vehicle for propaganda and a tool of surveillance. With the collapse of Communism and the end of a state-controlled press, photography could now become a medium for asking difficult questions and showing what needs to be changed. Photographers could now become photojournalists – reporters with a camera. I helped Slovenian photographers to make this cultural transition by running a series of workshops that looked at how to tell a story using photographs, and holding discussions about forming a professional photographic community as a way of providing mutual support and exchanging ideas. I still frequently lecture about photojournalism.

What are the main challenges that documentary photography has to deal with today?

Justifying itself.

Part of your recent work is devoted to an exploration of Jewish identity and we can see it in your book No Place Like Home. Was this personal approach some kind of inner obligation?

Yes – this was a very personal project. My father devoted his entire professional life to exploring questions of Jewish identity. A rabbi and a historian, he was fascinated by Judaism’s complexity, its subtle but profound impact on civilisation, and by the intellectual games it seduces you into playing. More than anything else, though, my father loved the fact that Judaism was, at its core, essentially an idea, and that everything that flowed from that big idea is just someone’s interpretation. Some of those interpretations are more interesting and perhaps better informed than others, but no one really knows what’s going on. As far as he was concerned, everyone is just guessing. He was fond of quoting Albert Einstein: “You know what makes God laugh? Listening to people making plans.”

When he died in the Fall of 2008, I found myself thinking about producing a set of photographs that would honour his values, his passion, and his vision. The No Place Like Home project was the result.

This book is a story about identity. About belonging. The photographs are a visual conversation with Britain’s contemporary Jewish community. They explore one of its defining characteristics – the ability to simultaneously acknowledge the traditional past, live in the creative present, and build for the future. They are about what drives us, what defines us, and what we do that gives our life meaning as Jews living in Britain at the start of the new century.

What are your plans for the short term?

I’m nearing the end of the photography phase of a five-year project I’ve been working on looking at issues of identity among the Arab citizens of Israel. I want to start editing all of the material and publish a book.

Judah Passow (*1949) graduated from Boston University in the United States in 1971 and has been working on assignments for American and European magazines and newspapers since 1978. Based in London, his work has been published extensively by all of the leading British newspapers and their associated magazines, including the Guardian, the Observer, the Times and Sunday Times, the Daily and Sunday Telegraph and the Independent. Abroad, he has contributed regularly to Time, Newsweek and the New York Times in America, Der Spiegel and Die Zeit in Germany, Elsevier magazine and De Volkskraant in Holland, Das Magazin in Switzerland and L’Express in France. A winner of four World Press Photo awards for his coverage of conflict in the Middle East, his photographs have been exhibited in London, York, Leeds, Glasgow, Amsterdam, Paris, Arles, Perpignan, Tel Aviv, New York, and Washington D.C. In 1995 Passow formed Further Vision, a new media production company, to explore the possibilities for combining traditional photojournalism with digital technology. His CD-ROM, Days Of Rage, based on his work in Beirut from 1982 to 1985, received critical acclaim in the British press for its journalistic integrity and technological innovation. He was an Artist In Residence at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1998, where he directed the New Media Centre’s Digital Photojournalism Laboratory, and has served as a consultant to the Soros Foundation’s Open Society Institute, training photojournalists on newspapers in the former Eastern Europe. He is a frequent lecturer on photojournalism at British universities. His book Shattered Dreams, looking back at twenty five years of his coverage of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, was published in 2008 and accompanied by major exhibitions in London, Hamburg and Jerusalem. It was nominated for the Deutsche Borse Photography Prize.

All photographs by courtesy of Judah Passow.