There are many invisible people behind the curtains who help others in their effort, and that applies to the world of documentary photography and photojournalism; it is not just about photographers themselves. Many people do a necessary and vital job to support and make relevant, so photographers can tell us their visual stories. One of the hidden “heros” is Maral Deghati who works as a photo-editor, curator, and project manager. I spoke to her during Slovakia Press Photo in Bratislava and she was so kind to find time to share her thoughts.

For some of us, you have a dream job. Meeting with photographers, curating and editing their pictures requires heightened visual sense joint with a gift to see the whole concept. How did you get into?

It is definitely a dream job, and it takes seriously hard work and character. Passion and curiosity are the drives but only with a strong work ethic and sense of responsibility does the dream become reality. I wanted a life of adventure and travel, meet people from all walks and learn about their lives, culture and their history. I left home at 16 and moved to Europe, I studied hard and tried to figure out what I wanted to do. I graduated from university with diplomas in Human Sciences and Fine Arts, bringing together my interest for the arts and humanity. After eight months of working as a fixer in Kenya, I got a job as a photo-editor at the international photo desk of Agence France-Presse in Paris and for the next six years, was taught by some of the best people in the industry, hard working women and men all across the world. I observed and listened with empathy, I think that’s key.

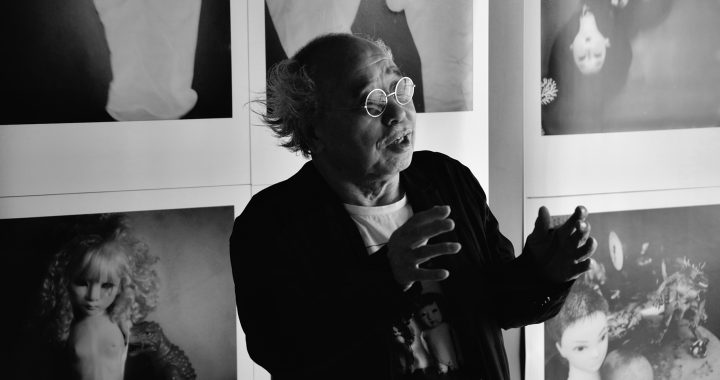

Portrait of Maral`s father the photojournalist Manoocher Deghati (Iran) in Italy, after 40 years of covering conflict worldwide.

Do you also photograph?

I used to, mostly to record and make meaning out of my childhood. I was born during a war, and my parents live in exile, so I grew up with a camera as silent witness to my life moving from one continent to the other. Through this I learnt about the power of photography to tell a story and how others may connect with it. It is important to know what it feels like to document a story, to be able to really assist photographers in their careers and reports through a cross-cultural framework.

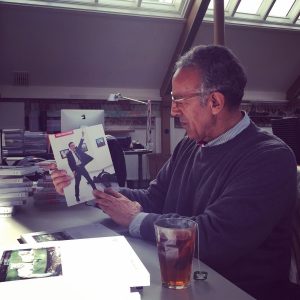

(L-R) Masters Magdalena Herrera & Jonathan Torgovnik during an editing session of Kevin Faingnaert’s work ZAD as Rebecca Uhlin, Mojgan Ghanbari and Dari Sulakauri listen in during the 24th Joop Swart Masterclass of the World Press Photo foundation in Amsterdam

When editing a photo series of a photographer, the whole series should be compact and pictures should follow each other in a natural rhythm. Are photographers generally aware of it when shooting the topic or is it your responsibility to do the final selection?

It really depends on the project, the final goal and the photographer. Photojournalism is visual storytelling with ethics so of course the photographer already has an idea, and because they are our eyes on the ground, it is important to work together.

There is editing and there is narrative. The editing is always better done with the photographer, who has the first-hand experience, but might still be too emotionally attached to certain images to make an objective choice in the selection process. Here, the photographer provides images that tell the story of what they saw at a 360° (a variety of images from close-ups, to portraits, wider shots), and then they are edited several times over. An edit consists of making a choice of the best images that tell the story; photographs that evoke emotion, provide information and are aesthetically successful.

Narrative is about the basic concepts of storytelling; we talk rhythm, style, movement and atmosphere. There is always a beginning, middle and end. It is important to keep the targeted audience in mind here, so the photos are accessible to the given public. Placing images in a particular sequence that take the audience on a journey to learn something new is successful when a team of journalists, editors, designers, and fact-checkers work together. This profession is all about teamwork, trust and leaving the ego aside.

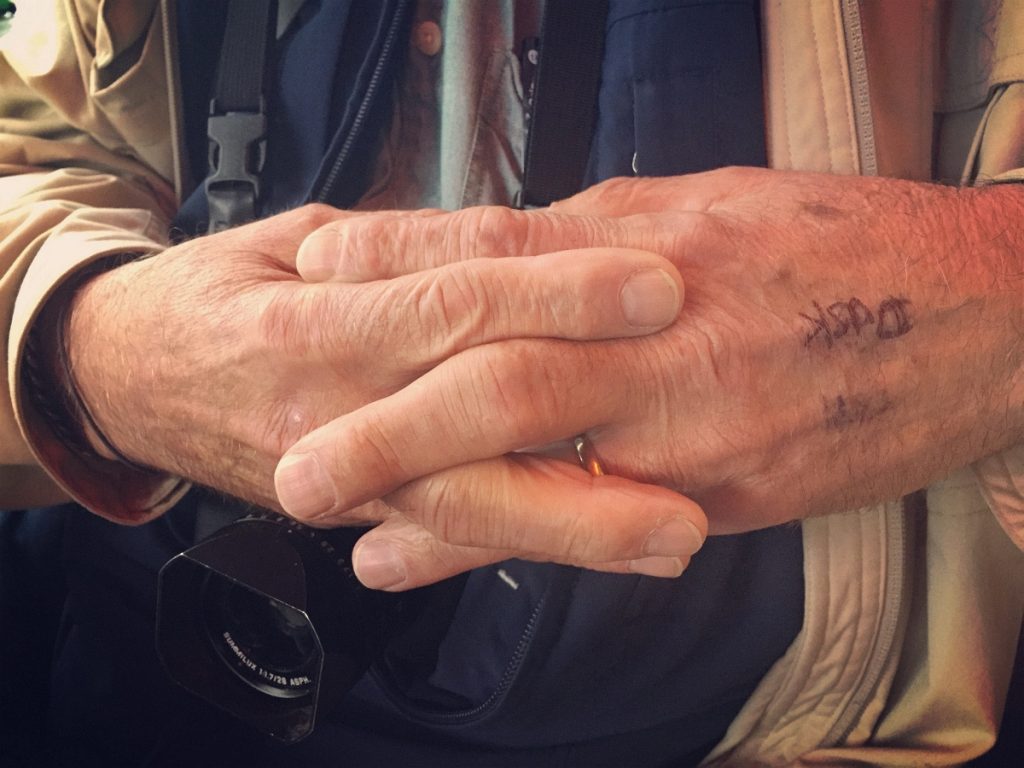

The camera and hands of William Albert Allard (USA) in Paris whilst working on his book Paris, which took him over 30 years before he felt it was ready. “Never rush a book, it is forever”.

Currently you are an education manager at the World Press Foundation and a storytelling teacher at Magnum photos. What is the main knowledge/legacy you want to pass to your students?

I used to be, but regardless of whom I work for, I continue to teach. Truthfulness, empathy, integrity and tenacity are some of the qualities that lead to successful photojournalism. It is a tough job, competitive and lonely – doubt is constant, and it is good to be conscious of this in order to overcome it. Allow yourself to be fully immersed in your stories, but always keep an eye in the rear-view mirror. Keep in mind that vision is subjective, but as professionals, we need to rigriously think objectively. Ask why and place yourself in the history of this storytelling genre. Reach out to the community, exchange, learn from those who came before you and don’t be afraid to ask for help!

As a festival programmer for the WARM Foundation, what is your role there?

We are a modest team of professionals living in various countries, so we all work together to make things happen. Throughout the year I’m actively scouting for content (films, exhibitions, conferences), review all the submitted projects before selecting and programming the seven-day festival. I then curate, produce and/or manage most of the photography exhibitions as well as curating, moderating or taking part in the conferences. During the festival I curate, moderate and ensure the smooth running of the festival and the guests.

WARM is an incredible project that needs all the support it can get, please join us!

You were a member of jury for Slovak Press Photo 2018. What feature/characteristics of a photograph/series is the most important for you when selecting the prize winning images in such a press competition?

The variety of stories that we saw shows the huge potential and interest in Slovakia for news photography. There was a wide range of topics covered in many countries in the world, and just because some works were not selected it does not mean they were overlooked. Judging is a long and difficult process full of questioning and compromise. What we saw and often what we discussed late into the day/night was related to the multiplying styles in photography today; we saw very different visual languages destined for different audiences from different cultures. As jury members, we hold a responsibility in setting the bar as to what aspiring photographers may try and reproduce in the coming years. Selecting the pictures that fit a category to tell stories that are universal beautifully framed and ethically approached was complicated, as there are many news stories that need more attention.

I’d like to see stories with more research and less dependant on dramatic visuals, and I encourage young photographers to subscribe to as many media publications that publish photography, read, listen to the radio, immerse yourself and become a specialist in the subject you are interested in.

How do you think today`s photojournalism is dealing with manipulation both in the picture and the story? Do we have today enough tools to reveal it?

Yes, plenty of tools, but I can count on one hand the media agencies and publications that use these tools. But that’s not the real issue. My main concern is that people forget that the majority of photo-editors work for a certain publication, so naturally their style and content is very much directed to a specific audience (Western). We lack strong platforms that highlight the stories photojournalists are working on in the world, and seeing that more than 45% of photographers are freelancers today mean they don’t work with photo-editors (allies who support the photographer in better telling the story, guided by ethics, and broader knowledge of the issues represented in their stories), which leads to cutting corners in this fiercely competitive world. By the way, studies show that most photographers do not intentionally manipulate their stories; it’s mostly out of its journalistic and story context, therefore a lack of knowledge and education on ethics.

Do you see any common trend in the visual approach of today`s documentary photographers?

Yes, the past generation would never dream of being so overtly subjective when reporting on a story – that’s for art and artists. Today, photographers are engaging with their own lives and immediate surroundings experimenting with styles and technique more aware of subjectivity, whereas before, the photographer was a silent witness, working as neutrally possible to bring a reality from a far away distant place we as viewers cannot see. Instagram and social media, through camera phones, have also diversified visual storytelling and potential audiences through its immediacy.

You`ve interviewed “war” iconic photographers Stanley Greene and James Nachtwey. Would you compare their approach? What do they have in common and what is the difference in their creation?

Yes, and what a privilege. Both Nachtwey and Greene share some exceptional qualities that have made them legends in the profession and beyond: consistency, dedication, humility, and honesty. Both men have a solid work ethic, and have sacrificed their personal lives to give voice to the voiceless, and shine a light where it is most dark on our planet.

This is an interesting comparison, a time when photojournalism and war photography is, again, being questioned. Well, just like in cinema, there are genres in photojournalism, and each have their audience. Their main difference lies in their visual language, and this is relevant to personal choice, style and vision, but let’s also keep in mind their editors and audiences (Nachtwey shot for Time Magazine whilst Greene was loosely based in Paris, working with European editors for most of his career).

James Nachtwey is incredible at capturing dramatic moments that show the whole story in a single frame. The emotions with which we experience the images are due to how he photographs the victims: with full dignity, but amidst the chaos of their situation: famine, war, and disaster. He peels back the layers and (cultural, geographic) distance between us and his subjects, reminding us the viewers of our similarities with the people photographed.

Stanley Greene has a background in the arts and fashion photography. He was a child actor in Hollywood and went to art school in San Fransisco. When he moved to Europe, he was hanging out with the poets of photography in France. Greene’s approach was 100% journalistic, but his visual language was his very own, from the gut. Cinematic, grainy, blurred and uncensored, he had a tough time being accepted in his native USA.

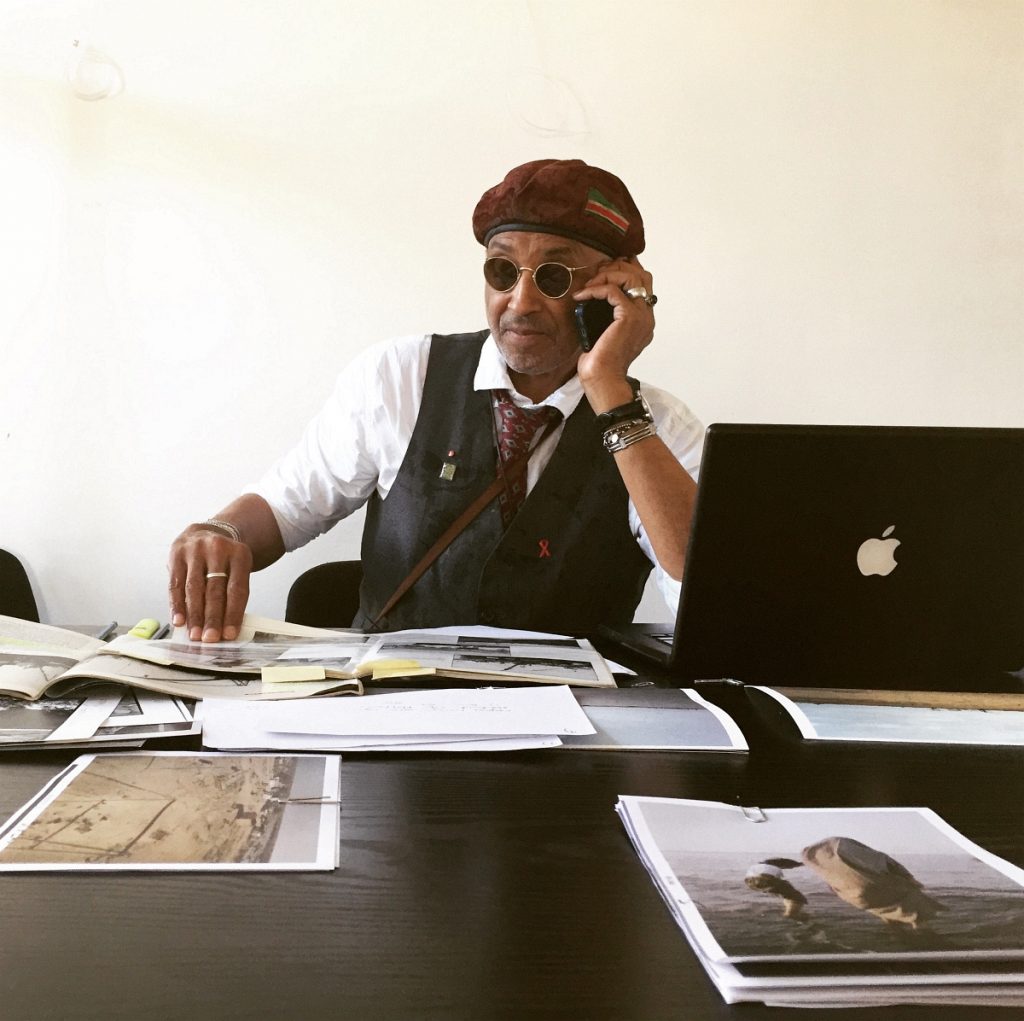

Internationally renowned photographer Stanley Greene (NOOR) working on the exhibition Along the Running Waves of the Caspian Sea for the CIP, at Dupon Lab in Paris 2016.

We are overwhelmed by huge amount of information and hundreds of pictures every day. How to support critical thinking in photography?

Bringing photojournalistic work into historical perspective is currently what is urgently needed in order to keep the profession relevant and sustainable. Through visual literacy campaigns for the professionals and the public for example. We also need to encourage a more structured approach to professional workshops and training, I like how there are now editors and writers invited to teach alongside photographers, a code of ethics and support in business and legal matters should also be part of the curriculum. With this, it is my hope that photographers will be able to cut through the noise by producing stronger stories that push the boundaries of the traditional means of working, and making sure the people that are photographed are heard. Photojournalism really does have a power, documenting and revealing truths as well as instigating public action, making it a weapon that can easily be misused.

Maral Deghati is an internationally professional photo-editor, curator, and project manager with more than fifteen years of practical working experience in photojournalistic reporting and management. She has worked in all aspects of the industry from reportage to sales, editorial and commercial and produces photography and multimedia narratives in collaboration with photojournalists worldwide on issues concerning developing and conflict stricken contexts across Asia, Africa and Europe. She is working on various projects, including festival programmer for the WARM Foundation, having just completed a mission as Manager Education at the World Press Photo Foundation.

Photographs above from the instagram account of Maral Deghati, photo in perex by Juraj Marec.