The perceptiveness of the image from which expressive moods come is the domain of Meg Hewitt, an Australian photographer, influenced by Japanese art.

What has led you to take up photography?

I have always been an image-maker. I studied painting at art school in the 1990’s but never pursued it as a medium. Regardless of this I would always imagine images that I would like to make, they kind of evolved in my head.

In the 2000’s I used to work long hours in a restaurant and wind down at the end of a shift drinking beer. I decided that it would be better to buy a camera and go for a long walk to wind down and I fell in love with it. I started to read everything I could about processing and printing film and I fell asleep looking at photography books. I felt that I had finally found my own personal way of image making, I would imagine the images I would like to make. So I developed my process to create them. I burned with the enthusiasm of someone who had fallen in love and found his or her purpose.

I always felt a strong need to find something I would love to do in life. Something beyond the everyday 9-5 routine. I grew up sharing my bedroom with my grandmother who was a cripple, she had a degenerative disorder that was never fully diagnosed and may be genetic so there is always the risk it may happen to me later in life. This drove me to walk as much as possible, to get out and experience as many things as I can. Ultimately we are all scared of death, but this personal experience and the sadness I sensed in my grandmother pushed me.

Your black and white images emphasize grain and texture; enhance drama and emotion without the distraction of colour. Why have you decided for black and white instead of the colourful palette?

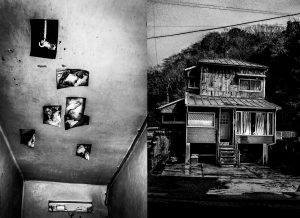

When I started shooting on film I couldn’t afford to process colour, so I would develop black-and-white film myself in the bathroom, I felt the kind of images I wanted to make, so it was a natural progression to shoot at high ISO with a flash, pushing and pulling the film then created part of the aesthetic. It emphasises grain and texture, enhancing drama and emotion without the distraction of colour.

The body of your work explores the layers between things through the fantasy and metaphor you find in reality. What does expressive art mean to you?

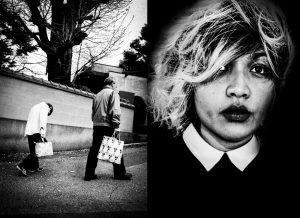

There is a saying that truth is stranger than fiction and on the streets I am constantly reminded of this. I also often have a sense of déjà vu as if I am living within a film playing out in front of me. Things are as I assume, within a plot. This feeling is heightened when I cannot understand the spoken or written language where I am. Scenarios become loaded with symbols sometimes I can’t straight away pinpoint the significance or find a metaphor but I sense something means more than what is at first apparent.

Expressive art goes beyond the first layer of things, it gets beneath the surface. I like images that make you want to keep looking at them, they draw you back to understand their layers. Sometime beauty is also in ugliness; things that are unexpected stay with you beyond the plethora of images we are confronted with everyday. Sometimes you stumble across an object or scenario that has a life of it’s own. Sometimes I spend hours photographing something to try and capture the fascination that led me to it.

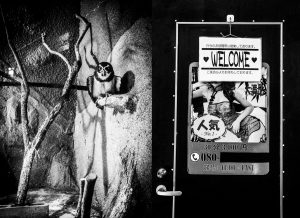

The series of your photographs named Tokyo Is Yours is inspired by manga, surrealism and film noir. It employs a similar high contrast aesthetic as the provoke photographers. How would you describe your personal philosophy behind photography?

I think the provoke photographers were trying to express some of inner truths it was a move beyond photographic realism. There is a pulse in the work like music. Much of the juxtaposition of images make the work, it is often in the edit and the sequence.

Film uses the psychology of memory to piece stories together. This is more dramatized in film noir. The lighting and symbology creates a feeling that goes beyond just pure dramatisation of a script. It was very influenced by early psychological theory as surrealism was as well. The German expressionists were an integral part of the birth of film noir and they were often inspired by things that repulsed them and made them to feel deeply.

Manga is like a film in a book. The images sum up the story; you don’t need to read the text to understand what is happening. I am better at reading images than text. And I like to explain things with pictures and diagrams.

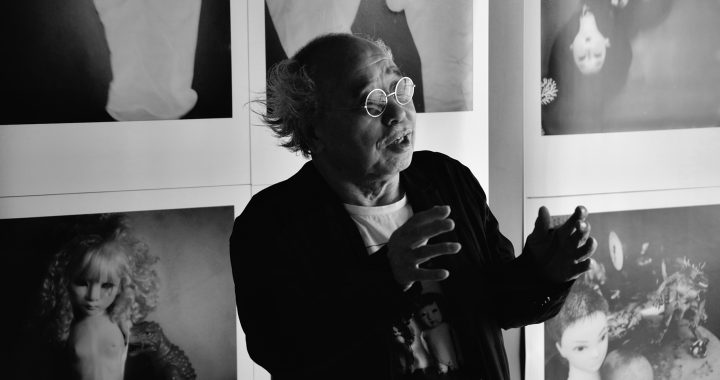

You have met some figures of Japanese photography such as Daido Moriyama. What has led you to follow Japanese philosophy in photography?

I met Daido when I exhibited at a gallery he is part of in Tokyo. He dropped by to look at my work but he could only speak in Japanese. I got a friend to translate. He pointed at one of my pictures and said I was dangerous.

I don’t think I was consciously following a purely Japanese aesthetic. The fact that this series of work is based in Japan probably feeds the assumption. Many of my early loves were Anders Petersen, Sebastian Salgado, Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and Trent Parke.

Since visiting Japan many times and meeting many photographers there I have become more impressed by Japanese photographers such as Fukase, he is my favorite. Plus there are a lot of photographers working there today who are not yet appreciated by the west and are very good. The Japanese have a very strong tradition in Photography and I love the bars, cafes and galleries there, which celebrate it.

As an Australian born photographer, how do you think is documentary photography perceived in your country and what is your opinion on its overall position?

There is a lot of great documentary photographers in Australia. I think there are not many avenues for them to create an income though it. Journalism is not paying, and the arts funding system does not support documentary style work. Art galleries in Australia are currently more interested in highly polished staged colour work. Australia’s documentary photographers have banded together is some great collectives such as Oculi and also the new women’s only Lumina Collective.

We have learned that you consider Jacob Aue Sobol your mentor. How did you get to meet him and do you think that his influence can be seen in your images?

I met Jacob in Tokyo during a Magnum workshop and then ended up assisting him in studio in Copenhagen. I suppose we were drawn to each other, as we liked each other’s images. After working with him I have learnt a lot about creating a proper inventory for prints, staying true to an edition size and being nice to people on the way up and the way down.

Has the work of fellow Australian Trent Parke inspired you somehow?

I love Trent Parke, he was one of my first true loves in Photography. He shows great skill, patience and an advanced way of seeing the world. I also admire the way he can tackle a different aesthetic successfully in each series he makes. You can see he works hard and doesn’t stop.

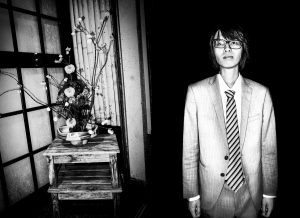

In your photographs dominate almost expressive vileness and very strong psychological aspect. According to which attributes do you choose the characters you photograph?

I photograph things that fascinate me and create a strong emotion. I may be fascinated by it’s beauty; it’s strangeness or its ugliness. If something repulses me it compels me to capture it. I often ask people if I may photograph them if there is something that interests me about them. If they say no, I move on but if they say yes I like to stay with them as long as possible and make many images, I like to talk to them and try and capture what makes them tick, what it is that fascinated me in the first place.

What have you looked for when making the body of Tokyo Is Yours and why have you decided to use a visual narrative that questions the human relationship with the world and each other regardless of origin?

Many things in our lives are the same regardless of language or culture. We love, we hate, we live we die. I like my pictures to be like stories that explore not just the difference between people and cultures but also the threads that we share.

After Tokyo, what is the next project you are going to focus your attention on?

I recently finished an artist residency in at the Tigermen Den in New Orleans USA and am editing together a series of pictures to be exhibited there as part of Photo NOLA in December. Next year I will be running a workshop in Tokyo in March and then exhibiting Tokyo is Yours at Anne Clergue Gallery in Arles during the 50th anniversary of the Rencontre d’Arles, which Annes Father Lucien Clergue established.

As a female photographer, do you perceive any advantages or disadvantages in the industry?

I feel it is an advantage to be female most of the time as people seem more likely to trust a woman that they don’t know. I do although think it would be harder in more macho situations or dangerous situations that require more physical strength. I can only speak from an assumption though as I have never tried to live as a man.

Photography is the photographer. And who are you?

See above..

Meg Hewitt (*1973) was born in Sydney, Australia and formally studied sculpture, painting and temporal media. She took up photography in 2010 and since then has been selected as a finalist in the Moran Prize for Contemporary Photography, the Head On Prize, the Lensculture Street Photography Awards and the Maggie Diaz Photography Prize for Women as well as being awarded a gold medal from the Tokyo International Foto Competition and a silver medal from the Prix de la Photographie, Paris. In 2017 she received fringe artist of the year at the Ballarat International Foto Bienanale and highly commended in the Australian Photobook of the Year awards.