The style as intriguing as his own name. Jamèl van de Pas is a young Dutch photographer, who without any further photography education, led purely by intuition, captures fragments in time based on life experiences – the world in its authentic form merges with the subjectivity of his point of view. Thus, photographing not the subjects themselves, but the way it feels like to see them offers the viewer a unique insight into Jamèl’s perspective of the world in black and white where nothing is good or bad, correct or wrong. The decision is up to the viewer who colores it. „That is my beautiful sickness“, states van de Pas.

You are only 20 but you have already published a few books. When did you realize that you wanted to become a photographer?

That is correct! For me, it’s a special experience to turn photographs into material objects, especially in this digital age. Printing a photograph onto paper makes it an actual ‘thing’ and ultimately, I believe in order for something to be truly desired it needs to be material. A photograph is, of course, a visual document, but a printed photograph is something you can touch and smell. Or if it’s a terrible photograph, at least you can burn it haha. Then, of course, there’s also the effect that one image can have on another when combined that interests me about making photography books. Sometimes two images have the ability to strengthen each other or seem to show a visual connection that wasn’t intended, which is beautiful.

I’ve been asked whether I know when I realized I wanted to be a photographer, but the truth is that it’s something that just happens. You feel like taking pictures and start doing so with whatever tools are available. In my case, this was a mobile phone for a brief period, before buying a ‘real’ camera eventually. From the moment you realize that taking pictures is something you just need to do when you see certain things, the moment you realize it’s almost a compulsive obsession, I think that’s the moment you realize you are a photographer. It’s not so much about having the ambition to be something but realizing that your own behavior makes you something.

You briefly studied photography. Why did you decide to quit?

A better way to put it is that I attended a couple classes haha. The students would get assignments that mostly focused on learning ridiculous photoshop effects, how to place the lights in a photo studio when taking pictures of a Coca-Cola can and taking ‘street portraits’ of elderly people. Often, I felt it was too silly to even take these pictures or spend my time on those things, so it quickly got to a point where I knew I wanted to quit. Because of my own lack of interest for the study program, even if I would have wanted to continue, I wouldn’t have gotten the degree anyway because I refused to develop the skills needed to be a commercial photographer. Now that we’re two years later, I have some images in my country’s national newspaper, so ironically, I may have had a ‘commercial success’ in a way.

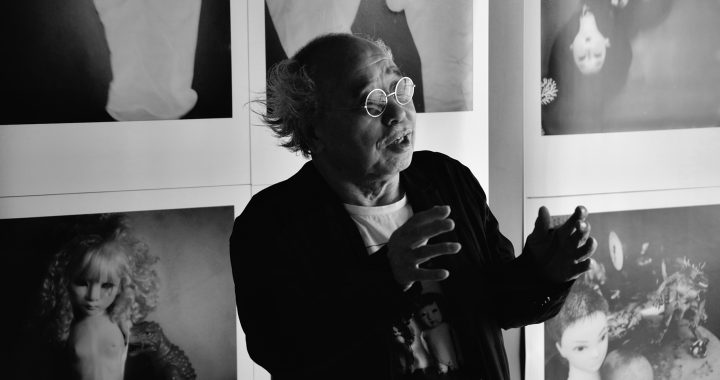

You share the similar language of photography as Spanish photographer Miguel Oriola and Japanese author Daido Moriyama. Are you inspired by them?

Miguel Oriola is one of my best friends outside of the world of photography and a strong colleague within photography. He’s been incredibly inspiring to me, but mainly in his ‘being a photographer’ and the way he is as a person. I think the fact that I share a visual language with Oriola and Moriyama has everything to do with the fact that the three of us are directly influenced by Takuma Nakahira, both philosophically and visually.

How would you describe your personal philosophy behind photography?

In the 1960s Takuma Nakahira, who was a very well-read existentialist and phenomenologist, wrote numerous essays, published numerous books and set up the now legendary magazine ‘PROVOKE’. Often misinterpreted here in Europe and in America, the aesthetic was not born out of a range of anti-war magazines that had high contrasted and grainy pictures (although they existed around the same time) but was the result of interpretations of European philosophers’ writings about existentialism and the act of perceiving the world. Having read Nakahira’s essays as well as the writers that influenced him, I must say it’s difficult to simplify it, but I guess I have the right tools available to attempt doing so.

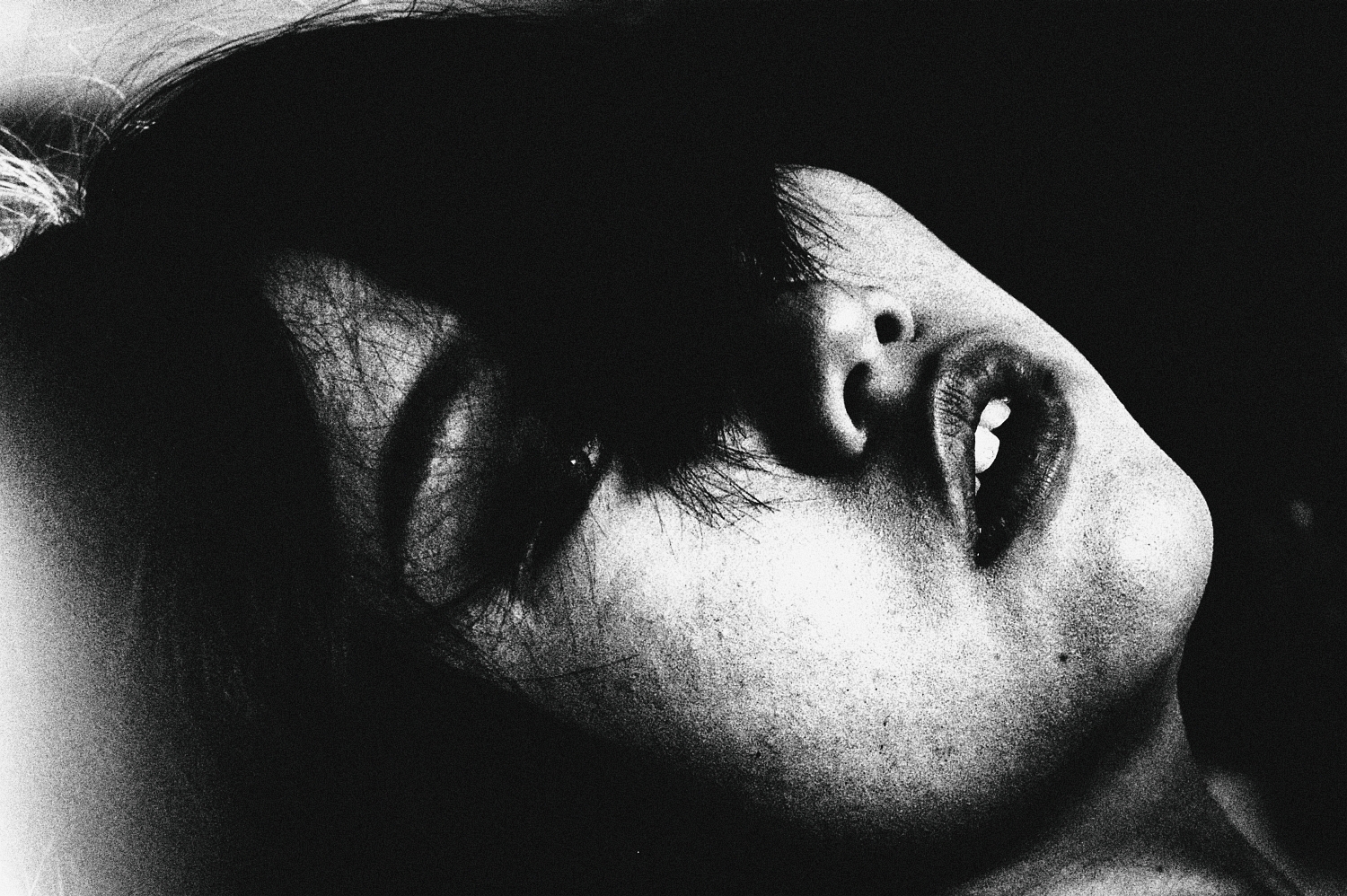

The basis lies in the experiment of trying not to capture what we see, nor how we feel about what we see, but what it feels like to see it. The act of photography is about copying the act of fixing your gaze on something. As we live our lives, our eyes will automatically and inevitably be attracted to certain things, breaking our cycles of consciousness. For example, as one walks to work or to the grocery store, we usually do this without consciously seeing things. For me, everything that breaks this cycle of ‘not being aware’ visually, is worth capturing. The moment I become fully aware of myself through the act of looking at something, an image demands to be captured. This image, whether it’s shot on film or digitally, is then placed in the photographer’s hands to be altered to the point where the photographer feels as visually awakened by the photograph as he was by the subject the moment he took the picture. We usually think in words or tend not to think at all, but these visual moments of ‘thinking’ are highly valuable and can only be documented using a camera.

Budapest, Berlin, Prague

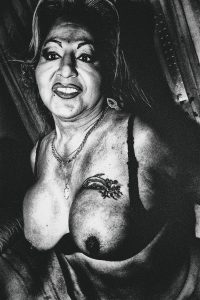

The body of your work consists of pictures that are visually provocative, such as intimate shots of women. Why did you include such moments into it?

This ties into my philosophy. Anything that visually stimulates me to the point of almost exclusively using my visual sense for a moment, is worth capturing. Sometimes this can be something ordinary, such as a trashcan that suddenly strikes me as visually intense. In other cases, it can be something more predictable, such as a woman’s body. The fact that it’s an often-returning subject in my work has to do with the fact that I both take a lot of photographs when I’m with a woman and that I often find myself with one to begin with. These encounters are a part of the collection of things that disrupt my daily cycle of not-seeing and not-thinking consciously and thus a part of my work.

Which role do the intimacy and exploration of sexuality have for you as a photographer?

They have no intended impact on my work because the shooting of images for me is free of concepts or personal ideas about the world around me. As you can probably sense, these reeks of a paradox of course. Whatever I feel visually excited by in a way has to be based on what I am emotionally sensitive to as well. This surely doesn’t go for all my images, but of course, in the context of intimacy and sexuality, there is already an emotional and passionate excitement in me, which can make me more sensitive to visual stimuli. In sexuality, there is an almost crucial visual element that makes something sexual. For concrete examples, I can point at the number of men that sleep with transsexual women, simply because they look feminine. In the act of sex itself, whether it’s about a sexual position in which both people have a provocative sight, or even something simple as nice-looking lingerie, the visual element carries a certain essence. In this way sexuality is almost like photography, it has a lot to do with being visually triggered, which makes sex itself something that can easily make me take a photograph.

According to which attributes do you choose the characters, especially women you photograph?

I’d say I don’t choose the characters but my eyes do haha. Since the question perceives that I have a notion of what I like before I take the image I think I can’t answer it, simply because I don’t have any. Looking back at whoever, I’ve photographed so far, I guess I could assign certain attributes to them, but often none that played a conscious role when photographing them.

What is the trigger for you to take a shot?

This is the mystery of photography, isn’t it? It’s safe to say there certainly is a trigger I can feel, it’s also safe to say this feeling is stronger than most other things I can feel. So, it must be real. What it is that activates this sudden desire and makes me take a photograph is unknown to even myself though. In a way, I’d like to say it’s a mood or the way something looks, but then again if you look at my pictures, the subjects look different from one another and so do the moods. The only thing that truly connects the pictures is that I saw them, felt something and shot them, so I guess there’s an interdependence between me and the world.

You have portrayed cities such as Prague, Berlin, and Budapest. Why did you choose them?

Shooting in Berlin, Prague, and Budapest was the result of a train trip I went on with a high school friend. We decided to visit the three cities over a span of about three weeks’ time and as I carried a camera with me, a project eventually formed itself. Shooting in the three cities wasn’t much of a choice. It was more a matter of going there and if there’d be things that made me take pictures, I’d end up with pictures. For example, we also visited Vienna but I didn’t shoot there because I didn’t feel like it, thus it’s not part of the project. As you can see I did feel like shooting in the three mentioned cities. I ended up publishing the project in the form of a book, which became the first one released by a publisher.

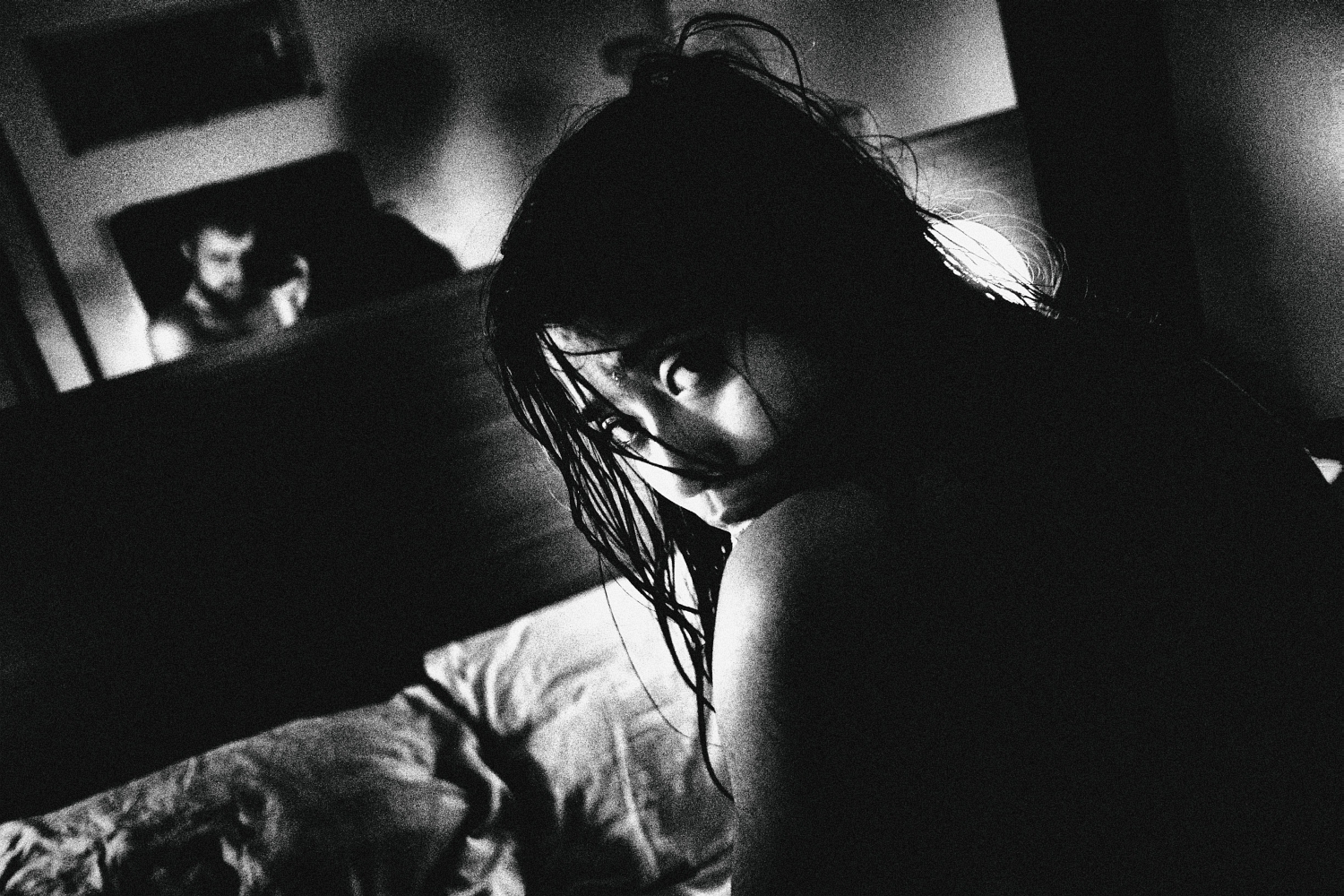

In the body of your work, it may be noticed that Asians captivate your attention. Why is that so?

Haha! Around the time I started taking pictures I was in a relationship with a Chinese girl, after which I got into a relationship with a Singaporean. Then half a year later, after that second relationship ended, I shot an entire project in the Philippines. As a result, the majority of my (photographed) love life up until now has been with Asian women and since my project about Manila seems to be getting the most attention so far, my pictures are again presented showing mainly Asian subjects. I don’t really have a preference though, be it photographically or aesthetically.

Manila

Did you focus on composition and storytelling while taking photographs in Manila?

Not at all, I never do. Copies of reality inevitably show the reality and in a way, convey a story, this is a side effect of taking photographs, but it’s never on my mind when shooting. The body of work shot in Manila can best be seen as a document of what it’s visually like to in Manila. It’s not so much about what Manila is or how I feel about Manila etc., but purely about the way the city penetrates the eye of someone visiting it. Surely a viewer can tell some of the people I photographed must have interesting background stories or that my encounter with them was an interesting one, but if I wanted to convey this I’d become a writer instead of a photographer.

What does this project represent for you?

For me it was the first time being in a place where I didn’t have to wait to be visually provoked my surroundings, constantly walking through an infinite collection of possible photographs. In a way, for this reason, it was a good way to see how I can experience photography under ideal circumstances and what the result of such an experience would be. I shot a couple thousand pictures while there and if it wouldn’t be a visual overdose, I could use most of them.

Why have you decided to use high contrast, sometimes grainy black and white instead of a colorful palette?

In my processing, I attempt to convey what it feels like to see whatever I looked at when I pressed the shutter. Maybe I experience the world in an overly nihilistic way, based on how others have described my visual language. To me, it’s natural that there’s a big difference between capturing what you see and capturing what it feels like to see it, which means the photograph can’t possibly resemble what you see. To further explain; sure, I can see colors but they don’t have an effect on the intensity of whatever I can feel looking at something, thus the colors should be removed from the final photograph. The contrast in itself naturally pushes contours and differences between light and dark to the max, again allowing me to push the visual experience of seeing to the extreme.

Every picture is an amplified slice of visual consciousness.

Jamèl van de Pas (*1997) is a young Dutch photographer from Tegelen, Netherlands. A few weeks after buying his first camera in 2015, he participated in a competition for the emerging photographers and has been featured among the 100 best emerging photographers of The Netherlands. The same year he also started to study photography, which he quickly decided to quit. Since then, he has published several books and his work has been exhibited in multiple countries throughout Europe and Asia, with the most notable locations and events being at the Seoul Museum of Art, EFTI in Madrid and at the Tbilisi Photo Festival. His photographs have been published in many magazines and featured on numerous websites.

Manila