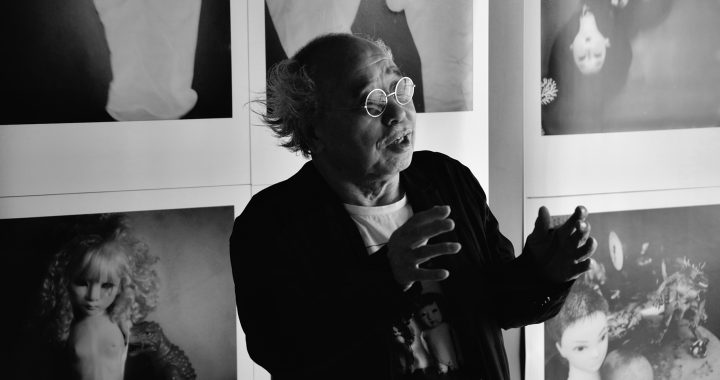

Ľuboš Dubovský with his photo series capturing a producer of traditional folk instruments living in coexistence with nature – Stano, have won the documentary photography award DOFOTOS 2017. Ľuboš is yet completely unknown in the field of documentary photography. His long-term attempt of valuable documentary photography capturing native culture of living of our ancestors (in Slovakia) is very well-founded.

How your personal journey of experiencing photography has started? Why are you interested in it?

Photography captivated me by its ability to capture a moment, to stop time, offering the possibility of expressing myself.

When I was a child, our father captured his surroundings with his twin lens reflex Yashica, and I was fascinated by this camera. I used to spend time with my father in dark bathroom developing films and enlarging photos. In adulthood, I have inherited his Yashica, which led me to photography. Back then, I used to be more attracted to the photography technique more than to photography itself. I have provided myself with a film SLR camera and started to aimlessly shoot pictures of anything around me. Having gone through shooting plenty of junk I realized that photography without people didn’t make any sense to me. At the time, each of my picture presented just bare information about the view from a mountain, about the sunset, the mist, and other visually attractive scenes. Even though I used to receive complimentary response, for me it lacked of any sense. So my attempts to capture people began. I created my individual, “conceptual” approach to basically validate my incapability of advancing towards people. However I managed to move forward. Those were my beginnings.

When did you start perceiving documentary photography as an art, which has its original idea and legacy in unique visualization of image?

I have always admired documentary photography. I have perceived it as top of the photography art, but it took me some time to encourage myself to start shooting documentary photography myself. As I mentioned, I acquired interest in capturing people and their stories gradually. For a long period of time I however wasn’t able of crossing barrier which restrained me from approaching with camera to the people neither physically nor mentally. At this point I took an extented break from shooting and dedicated myself to a traditional Slovak culture and I consider this interval very helpful. I got acquainted with people dedicated to traditional culture, which drew me back to photography. By capturing these people I understood the purpose of photography, that the visualization of a person is essential not just for bare effect. I have started reading books, exploring documentary photography and I was immersed in stories of people captivated on pictures. Photography is now much more sensible to me.

Who are your role models in the field of photography, whose creations you find inspiring?

I don’t have any role models, however production of some authors caught my interest, mostly social document depicting images of people living in outlying areas, therefore they are invisible for us. For instance I find inspiring people and their stories captured by Martin Martinček. I am also affected by Pavol Breier with his photos of shepherds. In addition I admire masterpieces by leaders in Czechoslovak photography, such as Jozef Koudelka, Antonín Kratochvíl, Tibor Huszár and other masters of documentary photography. Moreover, I am fascinated by creations of Matúš Zajac remarkable with elements of fine-art, pushing his photos towards expressivity. His approach is unique and extraordinary, therefore inspiring.

Do you consider photography webpages and other platforms as effective in right perception of the documentary photography, according to your experience?

For the right perception of the documentary photography are the photography websites utterly inadequate presentation method. Their administrators and community are not documentarists, therefore documentary photography here lacks the recognition. Facebook and other social media have the same impact. Documentary photography is challenging not just for the author, required to work with people, travel, communicate, overcome obstacles and master the photography, but for the viewer as well. The viewer doesn’t perceive a photo in the same way as an author, and he needs to comprehend and explore photography to understand it. Documentary photography don’t hinge on mass consumption or applause of the public. The real aim is to capture people and their stories which can’t be perceived superficially according to your own taste.

How you noticed the documentary photo contest DOFOTOS, have you hesitated with entering and have you questioned its seriousness?

I have been noticing “dofoto” magazine since its beginning and I was delighted with its existence ever since. As it is utterly unique in Slovakia, I have been tracking with pleasure each new article, thus I couldn’t miss the DOFOTOS contest. Immediately after its launching I wasn’t impressed, but the temptation of entering with my own pictures had been gradually increasing. Finally, after a month of launching I consigned my photo series STANO and I am delighted with my victory which pushed me forward. I wasn’t concerned about the seriousness of the contest, as the jury consisted of respected members.

How did you perceive your victory in this contest, did it increase your ambitions, has it caused any changes in your perception of documentary photography?

The victory itself hasn’t any impact on my perception of photography, but it did influence myself. I became aware of my responsibility of doing photography properly, of finishing what I have started.

What does the traditional Slovak culture, which you are documenting, mean to you?

National culture of Vlachs in its original form doesn’t exist anymore. It has become extinct by European Union directives and by a certain progress. Likewise, music culture of shepherds including bagpipes, various whistles, fujara (Slovak shepherds long pipe) and other music instruments of shepherds had almost completely vanished from Slovak traditional houses. This music culture of shepherd had moved to the villages and cities and is endangered by various attempts of using them for music which has nothing in common with traditions. As I am a producer of traditional folk instruments and also a performer, I am relatively a part of the musical culture, therefore I am concerned about keeping up with this tradition. Finally, traditional social photography document is in Slovakia equally endangered by new approach, stimulating me to connect these two matters which I care about and to make efforts to preserve them. However, in the field of photography I am not documenting traditional culture of Vlachs, because as I mentioned it practically doesn’t exist anymore. I am focusing on individuals tending to traditions and making efforts to its preservation in their own way.

Documenting life of a man with his beloved animal is blissful. Photo of “Stano” with his horse in a brook is exquisite. How do you manage to insert your own view into the final photo?

I take photos intuitively and according to my sensations. I don’t follow any specific procedure, I just apply gained skills and knowledge. Photo with a brook is the result of comprehension of conditions, anticipation and my quick reaction. We went for a walk with his horse, and all of a sudden Stano abandoned the footpath and entered a brook with his horse who struggled with walking across a bridge. I had to promptly outspeed and take a picture. I enjoy this photo, yet in this series are some which I appreciate more. They may have less effect but I had to put more effort into them.

How do you involve people on your photos in the direct contact with you? What is your way of communicating with fujara players?

For my photos I choose people not merely according their appearance but also according their nature. Therefore is essential for me to know them at least vaguely. As I have acquaintances in the circles of fujara players and producers, it’s becoming much easier. Nevertheless, there is an immense difference between performing with them and taking photos of them in their privacy. People generally aren’t very pleased with the lenses pointed persistently at them, especially in documentary photography where I approach them quite closely. It requires time, patience and reciprocal humility. For instance it took me more than a year to shoot a series of 15-20 photos which I was satisfied with. Spending time with people, being honest and sincere is necessary. Eventually is up to them how open they become and how deeply they let me enter into their personal space. This naturally relates not just to fujara players but to all documented communities as well.

You know intimately the backstage of Slovak folklore, aren’t you tempted to take a close-up look at it through photography, or is it a taboo?

I don’t consider the backstage of folklore as a taboo. It is indeed an interesting topic, but yet I am not attracted by it as a subject of photography. Folklore and theatre are very much alike. Performance on a stage is all rehearsed, and in the backstage everybody is focusing on performing the best interpretation. Basically every backstage shooting is a bit artificial and I prefer spontaneity.

How do you manage to combine your profession, various hobbies and your family with your dedication to the documentary photography?

I have an extraordinary job which allows me to devote enough time to my hobbies. I go shooting usually on weekends, but by far not each weekend is dedicated to photography. Consequently I have plenty of time for my amazing wife, which is supporting me in everything.

As a winner of contest “DOFOTOS 2017” you have participated in gipsy themed workshop by Matúš Zajac. How was your experience? Are you satisfied with your result from this workshop?

I find this workshop very interesting and revealing. It was filled with emotions and new experiences. Taking pictures was quite problematic as gipsies are peculiar and eccentric living souls. Entering their colony with a camera and capture from a short distance people which you see for the first time is an extreme situation. In some cases it got even dangerous. Nevertheless, they were quite willing to be photographed so I managed to take some pictures. Honestly, my intention was to gain experiences and skills, and I was aware of the possible scenario of not making any actual photo. Eventually I took some pictures, however I could not be satisfied with the result without long-term capturing of the particular community. Regardless I am very grateful for the opportunity of experiencing it and gaining knowledge about documenting.

I would like to express my gratefulness to Matúš Zajac for my participation on this workshop as a prize for winning the DOFOTOS contest.

What are your goals for the future, your own exhibition or even a book, or rather modest presentation and ongoing study of documentary photography and diverse stories of people?

I slightly described my goals for the future already. I intend to keep documenting extraordinary people. People who achieved and created something not merely for themselves but for the society as well. People who live their life faithfully…

If I manage to finish what I have started, I might probably want to publish a book, but not any time soon, because I intend to document various topics. This hard work will require plenty of time and self-education. Those are necessary and indispensable elements of every creative process.

Translated by © Simona Krejčí