Giving a voice to communites which are hidden from our everyday life is the main goal of many documentary photographers. Close human contact makes great pictures but certainly there is more behind if you want to display the truth. You need to be physically strong and have inner integrity to take photograps in such conditions as Valerio Bispuri did. He has worked on series from South America for 10 years and displays inmates from 74 prisons. In other series he deals with drugs, lost of human potention, human trafficking, diseases. Demanding topics presented in a visually artistic style.

Why did you become a documentary photographer?

I’ve started being a photographer almost by accident. When I was eighteen a friend of mine invited me to take a photography class. I never stopped taking pictures after that. I decided to become a professional photographer when I was thirty, when I moved to Argentina, in 2001, during the economic crisis of that time.

Your series Gypsies, Encerrados, The Paco and Prisoners from my point of view carry the idea of freedom, the basic human right and need. What is the difference in approach they were shot?

What I’ve always tried to do, it’s to give voice to the invisible ones, to those who are distant and marginalized. The work about Roma people was my first work, just recently I have restarted the shooting, it still is an unripe narration, but it always moves forward to the idea of giving back a sort of freedom of image. The other three projects follow the same line, but they are looking for a greater idea that goes deeper, besides freedom.

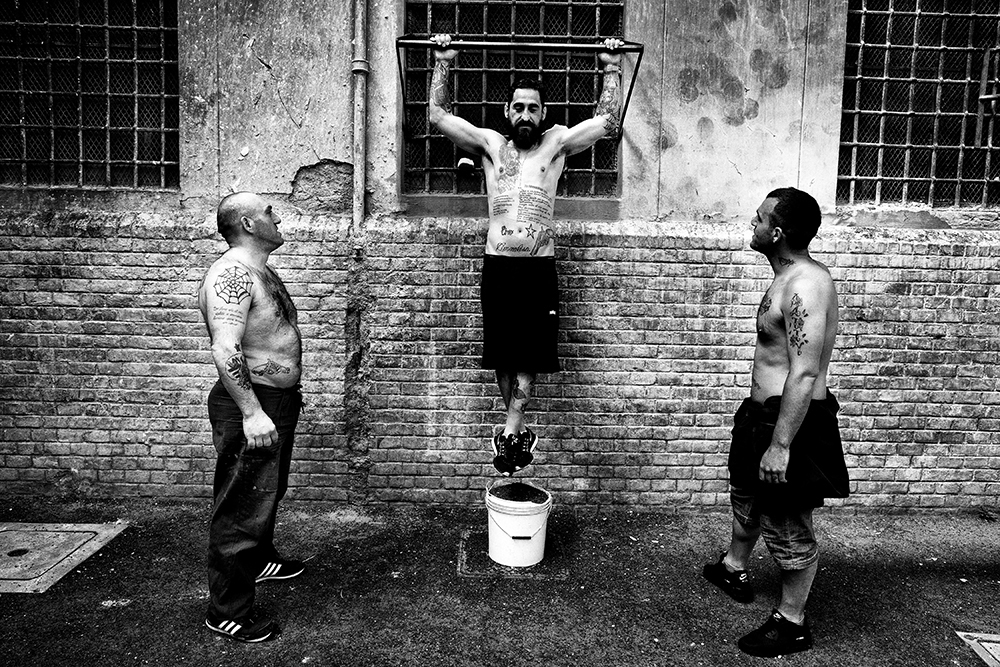

Book Encerrados deals with 74 prisons in South America and in your words it is a story about this country. It took 10 years to capture and was finished in 2014. Have you ever visited these prisons since then?

No, I never went back to South American prisons, but I have presented that book many times in Italian prisons.

What was the worst situation you experienced while working on that project? Mendoza, Pavilion 5?

Unfortunately I experienced many times dangerous situations, there always were some prisoners who didn’t like my presence. The warden, the official in charge the Mendoza Prison did not want me to enter Pavilion 5. He didn’t want to take responsibility that my life and the lives of the police officers who accompanied me could be in danger. So I asked to go in on my own and had to sign a paper where I took full responsibility for what could happen. I went in and the inmates welcomed me well, showed me the terrible conditions in which they were forced to live, told me their stories. In fact, in those minutes I spent with them, I didn’t feel any risks.

Encerrados

How did you perceive the psychological aspect of such demanding meetings with inmates?

There are unconscious consequences that I probably don’t fully realize yet. I surely haven’t slept well at night for many years.

What was the difference if you can appear male and female prisons there? Are they driven by the same rules?

Between female and male prisons there are some differences. Between women there is more solidarity, collaboration. There’s also more affection, physicality. They have no problem giving each other a hug in difficult times, out of a need for affection. In male prison, this happen less.

Have these experiences changed your perception of life and death?

Those who dedicate themselves to this work always “walk” on a difficult border between life and death, not only their own, but also the death of others. I also believe, as before, that what you perceive emotionally and in your experiences, it is something that stays inside yourself.

In Encerrados I often see diagonals which divide pictures to several stories. Was it an intention or is it your general approach when shooting in interiors?

Those who see the photos notice certain visual lines of the image. I believe that a photo reporter shoots in a dimension of pure instinct, but this can only work out if there is a previous, careful preparation of the shot itself.

What do you think is the main role and a goal of a documentary photography today?

I think that the most important role of documentary photography today is to narrate stories in depth, in opposition to the fast pace of the news that tell the facts without deepening the contexts. The purpose is to give a voice to those who don’t have one, emerging from the condition of invisibility in which so many human beings in vulnerable conditions still live.

Prisoners

I am sure that the Italian prisons have different philosophy and approach than the South American ones but one feature is common. The lost human potention. Was this the motivation to follow this topic in Italy by working on series Prigionieri [Prisoners]?

The idea of photographing Italian prisons was born during a presentation of Encerrados in the Poggioreale prison in Naples. During the debate, a prisoner asked me to go and photograph them too and this proposal caught the interest of the prison director. This invitation gave me the opportunity to enter a different prison world from the South American one, where I pursued the same goal: to narrate the prisoner from a human, existential point of view. The conditions of the prisoners obviously interest me, but that wasn’t what I wanted to tell, but rather the daily life of the prisoners, their glances, their thoughts and feelings. Mine is an anthropological work about their condition, my urgency is to describe their human dimension. The rest of it comes of its own accord.

Drugs, the most common reason why people end in jail. You took a separate series called The Paco which focuses on depicting the production of this new low-cost drug in the slums outside Buenos Aires. You shot it in color. Why?

In my works I choose whether to use black and white or color based on instinct. In the case of prisons I decided to use black and white because inside prisons there is no color, everything is almost monochromatic. For Paco, instead, I chose color because what I am talking about is not only drugs and those who use them, but everything that revolves around them, and it is a complex, varied world with many colors and shades.

Paco

What is your approach when shooting reportage comparing to work on documentary series?

Since photography has become my work, I have embraced a single philosophy, the one of depth. I’m not interested in telling the facts, but the complex worlds that surround them. It takes time, observation, deep knowledge of situations.

The journalism itself goes through big changes related to social Medias and internet. Classic newspapers are almost gone. Do you think that also the perception of the picture is now different?

Definitely. By now, we are used to seeing hundreds of pictures every day and even the most extreme ones, we are no longer surprised as we used to be. Nevertheless, I believe that it is still worth to make images to tell the human condition, to put in front of everyone’s eyes the situations of social injustice and existential unease.

What topic are you currently working on?

I am currently working on three projects: the first one on the psychiatric and neurological diseases in Africa, which I recently started, another one on the trafficking of women in Argentina, which I have been following for several years and I have almost finished a reportage on the world of deaf people.

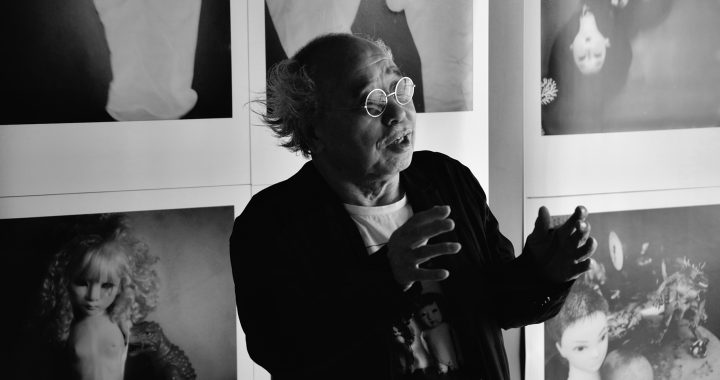

Valerio Bispuri (*1971) was born in Rome and after graduating in Literature he decided to devote his attention to photography. Professional reporter since 2001 he collaborates with numerous Italian and international magazines, among which L’Espresso, Il Venerdì, Internazionale, Le Monde, Stern. He has carried out reportages in Africa, Asia, Middle East, but it is in Latin America that Valerio worked the longest and has lived in Buenos Aires for more than a decade. He has worked on “Encerrados” for 10 years, a long term photographic project on the life conditions in 74 prisons across all the countries in the South American continent, describing with an anthropological and journalistic approach, the inmates’ reality. This work has been exhibited at Visa pour l’Image in Perpignan, at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, at the University of Geneva, at the Browse Festival in Berlin and, in October 2014, at the Bronx Documentary Center of New York. In November 2014 “Encerrados” became a book edited by Contrasto. In 2015 Valerio finished another important photographic project that lasted for 8 years, denouncing the diffusion and the effects of a new low-cost drug called “Paco” that is killing an entire generation of youths in the suburbs of South American large cities. The work on “Paco” has been exhibited in Rome, Milan and Istanbul (catalogue published by International Green Cross). He has been awarded numerous international prizes: Latin American POY 2011 (honourable mention); Sony World Photography Award 2013 (1st prize Contemporary Issues); Days Japan International Photojournalism Awards 2013 and the 2014 POY (2nd prize, Feature Story Editing – Magazine).

Survivors

Interview is authorized. All photographs by Valerio Bispuri.

Translation from Italian to English thanks to Katarina Jaramillo.