The civil war that ravaged former Yugoslavia, his home country in the 1990s, determined his style. His raw, monochromatic pictures are an emotionally vivid documentation of everyday violence in a city plagued by neglect. Winning in a green card lottery was his ticket out and a chance for a new beginning in the United States. There, he started uncovering everyday life in the American ghettos that fester in the shadows of the American dream. Boogie, born Vladimir Milivojevich, encountered situations not many of us would dare to. After this experience, the normal life to him just did not feel real enough. Even though he tasted commercial success while working on ad campaigns for major global brands such as Adidas, Nike, and Puma, it did not compromise his style. Without planning, and aiming to be surprised, Boogie continues to portray the dark shadows of urban life and people on the margins of society.

How did you come up with a nickname Boogie?

Haha, maybe like 35 years ago kids started calling me Boogie because of some movie called Boogieman. I do not know why, I’m such a nice guy. But you know… it’s perfect. The nickname stuck with me. And come on, it’s much easier to remember Boogie than Vladimir Milivojevich.

Why did you take up photography?

My dad was an amateur photographer, my grandfather as well. The cameras were kinda all around when I was growing up. It was just a matter of time before I started using them. But I was never really into photography when I was a kid. My dad was always trying to get me into photography. But when these protests in Serbia started, especially when they turned violent, for me it was just natural to go out and try to capture something. You know, when you are shooting, when you are behind the camera, you are an observer, you don’t feel like you’re participating. You shoot and you feel like you are not part of that shit. It feels better.

So you were more of an observer rather than a participant?

Oh yeah. Thank God I was younger. I understood what was happening, but it would have probably killed me now.

How old were you?

20 something.

You were witnessing everyday violence and countless protests. How did it feel like to be out there on the streets amongst your people?

You experience it differently, it’s your country. Your people’s misery affects you in a different way, you feel with them. When it’s your people; it affects you on a deeper level. It was kinda hardcore and depressing.

Did growing up in a war-torn country affect you somehow?

Those were the dark days. My country was fucked up. I started shooting at that time, and it affected my style and it made me who I am. In terms of photography, it made me who I am, it had a big impact on the way I see things.

Your images captured battalions of riot police standing in formation amid one of the countless protests that marred the decade. Do you recall any specific moment when you were really afraid?

Of course, like running from the cops. You know, it’s like a cavalry stomping towards you. I remember being in front of the cops, shooting, and all of a sudden they started running towards protesters. You run for your life. You fall down, and before you know it, you are back up and running.

When did you leave Serbia for the United States?

I was in Serbia throughout the civil war before I left in 1998. I wasn’t thinking about leaving at all, I was just drinking with some friends one night, and we all applied for a green card lottery. And I was the only one to win. So I was like, ‘I have to go, you can’t be a pussy and not go.’ If you don’t go, you will ask yourself your whole life what would have happened if you didn’t go. If an opportunity like that arises, you have to take it.

Did you go there by yourself?

No, I had a girlfriend at that time, and basically, I called her up from the American embassy in Belgrade, and I asked her to marry me. I had to do it for her to go, otherwise it would have taken years. So I asked her, ‘Do you wanna marry me?’ And she said, ‘Yeah, sure,’ haha.

You got a chance to taste the American dream. What did it feel like when you first arrived there?

I arrived in New York, straight into the belly of the beast. The thing is I had no money; I come from nothing and I was lost… When you watch movies or when people tell you it looks so easy there, that they’re all waiting just for you… it’s so far from reality, it’s ridiculous. Especially being a Serb in the nineties, oh man, it’s hard for any kind of immigrant from Eastern Europe, let alone one trying to make it in some creative field. People think if you’re from Eastern Europe, you can be a mathematician or a chess master, haha, but not an artist!

How long did you live in the United States?

Eleven years.

While you were in New York, what were your expectations of making it in photography?

I went to New York and I was like, ‘I’m gonna kill it in photography.’ But I didn’t realize that no one wants you, and no one needs you. And I basically worked some odd jobs- whatever I had to do to survive- and I was doing photography. I would wake up at 5:00 AM, shoot, go to work, shoot after work. But then I stopped taking photographs for 2 years. I sold my cameras on eBay, ’cause look, if no one believes in you, you stop believing in yourself, and that’s the worst thing that can happen. And that happened to me. For 2 years I was like, ‘I’m not gonna do photography ever again.’ I did web design in the meantime, and I was very good. I had a background in programming. And then by chance, I built a website with a bunch of my shots from back when I was shooting, and I had 30,000 visitors in the first week. I thought well, maybe I should start shooting again.

Why?

I was better than before the break. It was as if I needed that break.

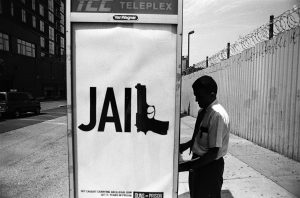

After the break, you started portraying everyday lives in ghettos in New York. What led you to this topic?

I was photographing junkies for a long time, and I got really depressed from shooting people smoking crack all the time. I needed a break, so I went to these public housing buildings and I tried taking photos of some gangs. I went there, and I was just walking around with my camera. White guy with a camera in their neighborhood, it’s not something you see often. And these guys came over, we started talking, they liked me, and I started hanging out with them. Then a couple of weeks later they were like, ‘Hey Boogie we wanna ask you something. Would you mind taking photos of us with guns?’ I thought, ‘This is not happening,’ haha. ‘This is crazy,’ yeah. And so I took it from there. I was getting deeper and deeper.

How did you gain access to these communities?

I don’t know. I just went to that neighborhood, I walked around, and I bumped into some people, I hung out with them and then one thing led to another. I met some girls, we hung out, and then they were like, ‘We’re gonna smoke some crack now, do you wanna take photos?’ And of course I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ And one thing led to another and another and before you know it, you are in some kind of hell.

It was you and your camera in the underworld. How did it feel to be on those streets amongst people on the margins of 90s society?

You know, it was just great; it felt like being in a movie. You are seeing something that no one else gets to see. It’s actually better than being in a movie. It’s real, it’s crazy, it drives you in it, takes over your life, and in the beginning it’s just a project. Oh yeah. But then, it takes over and becomes the most important thing in your life. It’s weird. I would go there, hang out with these guys, gangsters, and then it was just weird hanging out with my friends. That normal life, just didn’t feel real enough anymore. It was a different kind of reality. Being with gangs felt more normal than drinking beer in a bar.

Where is the line? Did you become close to these people?

Yeah, we were friends. The thing is that people tell you there are some lines you should not cross. And that’s the truth. But the deeper you go, the more interesting photos you take. That’s a fact and no one can tell you where those lines are. And then all of a sudden they were discussing who did they wanna shoot in front of me. And I didn’t wanna hear that, I didn’t wanna know any of that shit. I was like, ‘Fuck man, I need to leave. I need to get out.’ So then I went back to shooting junkies, and after a while, I went back to shooting gangsters again. I ended up going back and forth between them.

Was it difficult?

Yeah, it was hard, but interesting, very interesting. Difficult to stay out of it. Then, all of a sudden, that other stuff is not really interesting enough anymore. I was used to looking at guns and needles. You need time to get back to seeing photos elsewhere. There are shots everywhere.

You, as an outsider, were able to convince criminals to incriminate themselves by taking the pictures that could be used to get them indicted. Were there any moments when you encountered fear?

You need to listen to your instincts, to your gut. It’s the only tool you have out there. If you notice someone is looking at you in the wrong way, just get the fuck out of there. A shot is not worth dying for.

You were in their community. If something happened, would they stand behind you?

Yeah, I had some real friends there. I’m pretty sure they would have.

When did you realize it is the time to put an end to it?

I was in really deep, but I started repeating myself. I realized I started shooting the same stuff over and over again. I remember going there so much that I knew all of them, and everyone knew me. They’d asked me, ‘Hey Boogie, do you wanna take some pictures?’ And I’d be like, ‘No man, I’m fine, I have enough.’ I got bored with it. And it was just in time. When the book came out, I went to these gang guys. They took me to some apartment where they held guns and drugs and I asked, ‘Fuck man, why now? I needed this for my book.’ And they were like, ‘Man, you could have sent us all to jail but you didn’t. Now you can see it all.’ I put those images into my anniversary edition. They made it to the book in the end, so it’s all good.

Are you in touch with those people you photographed in ghettos?

No, I’m not. I kept going there after the book was released. I showed it to them and they loved it. But then it became so depressing because you realize everything remains the same. The same stories. Nothing ever improved in their lives, and I knew I couldn’t be around that anymore.

When you started to have this feeling of repeating yourself, you switched for commercial, right?

It kinda happened at the same time. While I was shooting gangs and drugs, I was approached by Nike.

Shooting gangs on one side and doing ad campaigns for major global brands such as Nike on the other. Not to mention openings for the series, How to Make it in America. It’s completely different, isn’t it?

Yes, it is, but it’s still me. When these guys hire me, they hire me for who I am. You have to stay true to yourself. That is all you have.

You said you are not planning things.

No, I don’t really believe in planning anything. In life, or in work. You never know what’s going to happen. You plan and then your plans don’t pan out. It’s better not to plan and shoot to be surprised. That’s what life taught me, haha.

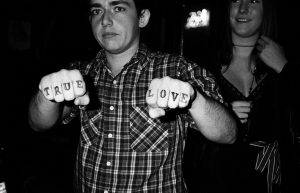

What about the images of gangsters showing off their guns? Were those shots posed?

It was not posing… In a way, yes, but it was all real, natural. I never told anyone what to do. They were doing it all themselves. I don’t do stuff like that, I just observe and shoot.

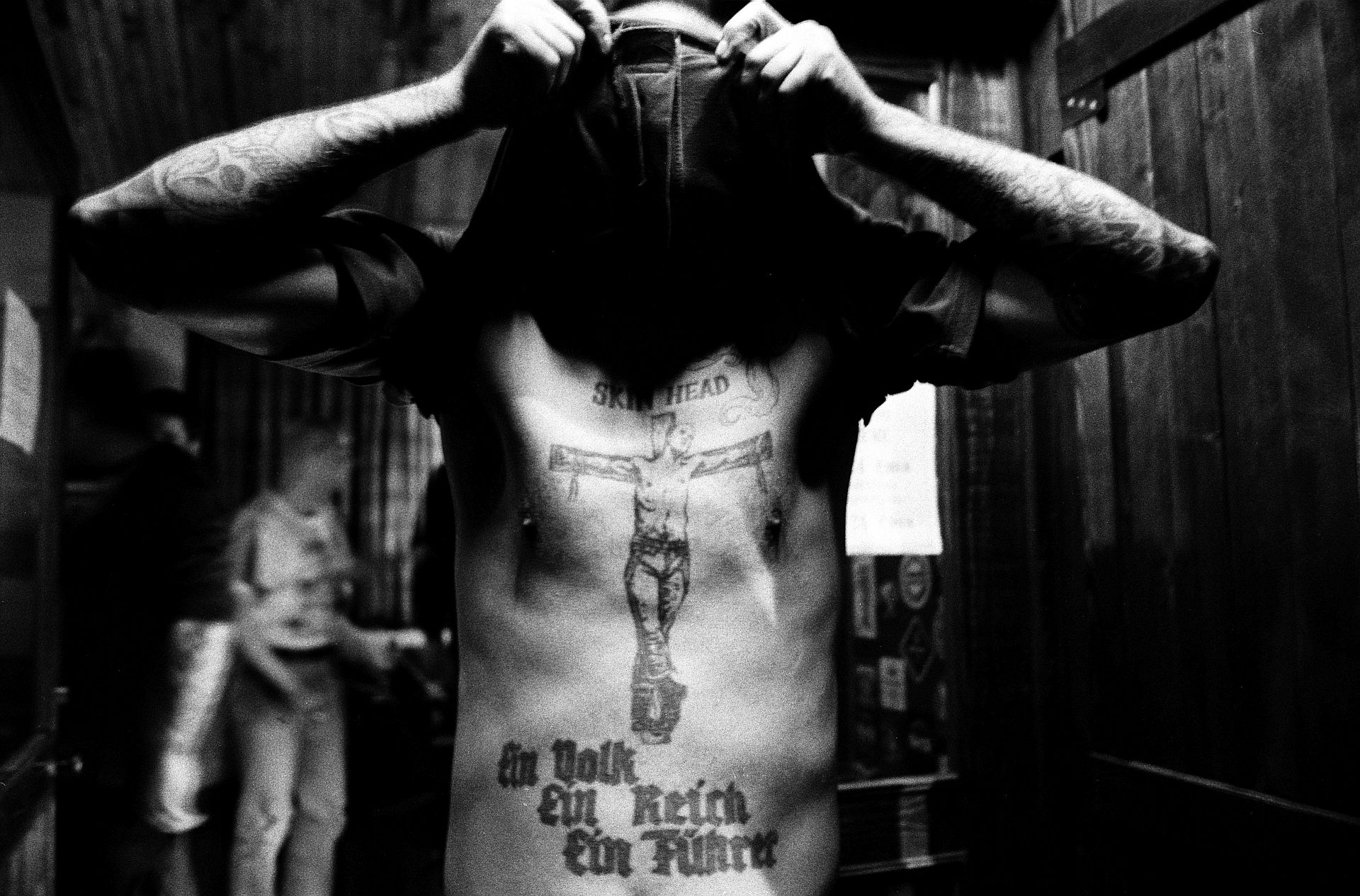

Your work includes skinheads as well. How did you get to work with them?

Some of my friends were supporters of one of those football clubs. They were football fans and football fans are the most aggressive. Some of them were skinheads, so one thing led to another and I became friends with these people, I hung out with them and they let me into their lives. It was the same as with everyone else.

Skinheads, Belgrade

Do you perceive any difference between photographs of communities, such as gangs, versus street photography?

It’s the same thing; there is no difference at all. You just react and shoot. That’s the point. You need to be one with your equipment, one with your camera, and then just react. I think that’s the key. If you think, you lose the shot. I try not to think too much about images. Thinking is the end of me.

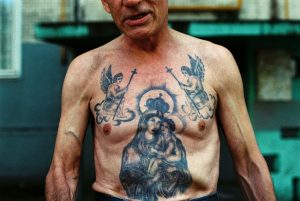

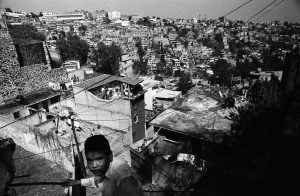

Brazil; Jamaica; Moscow. Why did you choose such controversial and different places?

It all happened by chance. I had some contacts in Kingston, and I knew some people in Brazil. The first time I went there was a long time ago. But recent trips to Rio and Sao Paulo were because I worked there for Nike, and I stayed longer on each trip to shoot for myself. And Moscow. I love Russia. Russia was Serbia’s ally throughout history, the only ally we ever had. I wanted to shoot in Russia because I had never been there before, and it seemed like a weird, huge, vast empire. I had some contacts with football hooligans there, and they knew people who lived in Moscow, so it was a natural connection. I went there three times. Shot a bunch.

Isn’t it easier to photograph, for example, in New York? Such cities have the atmosphere already within them.

The thing is, no matter where you go, you will get bored. Now, when I go to New York, I’m not really as inspired to shoot it as I was ten, fifteen or twenty years ago. It gets boring. I think that traveling is so important. It’s great. You get to see how other people live, and you appreciate where you are. You can position yourself better if you see how people live in other countries. They either live better or worse, so you know where you stand. You recharge your batteries. And every trip changes you. For example, Barcelona has been shot forever. I wouldn’t even go to Zurich or Stokholm, hell no. Boring.

You have already published nine monographs. How many are in black and white?

Five. Moscow and Kingston are in color, and also Belgrade Guide, which was published here in Serbia. So, six are published in black and white.

What is it that attracts you to monochrome?

For me, it was natural. Streets, black and white, Belgrade, and the period when I started shooting–it all made sense together. It’s kind of grey and dark, and so it’s totally black and white. For a long time, I shot only in black and white. This one day in Brooklyn, I went out and when I came back, I put a roll of color film in my camera. And that was that.

Was it just an experiment?

Yes, no philosophy. People like to sound smart and important, but I think it’s much better if people think that you are not very smart, and then you surprise them. They don’t see you coming haha.

When you edit and select photos for your books, do you do it on your own or you have someone helping you out?

You can always use another set of eyes, but sometimes it hurts to hear what someone else thinks. As a photographer, you get attached to certain images for various reasons and you wanna see them in the book. But the images you love might not be the best ones, so you need someone around to open your eyes and keep things objective. In the Moscow book I worked with a friend of mine. He is a graphic designer and helped me with laying things out and editing. It’s always okay to have someone else out there helping you out.

So for the most part, is it your work?

I do the wide edit myself, of course. But it’s really a pain in the ass. I love it, but it takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s so important. You can have great photos actually, but your book can be shit. You might not have those great photos, but the book can be killer.

Regarding photo selection, how do you decide which shot is better than the other one?

Over time, you learn what works and what doesn’t work. That’s just how it is. It takes time and practice like everything else.

Do you have any inspiration? Your style shares some similarities with Davidson or Richards.

I started photographing in the 90s in Serbia, without the internet and without money to buy books, so in a way it was a blessing because I developed as a photographer on my own. I developed my style without trying to emulate others too much. I was and still am just doing my thing.

You are a self-taught photographer. What do you think about getting an education in photography schools?

It can not hurt you hopefully, but talent and hard work are what counts. Of course, it’s good if someone gives you basic knowledge. But you know, technical stuff, it’s all online anyway. You can just Google it. It’s crucial to work your ass off, to see things. Good shots are everywhere. You don’t need to travel to foreign countries, to Africa, to wars and stuff like that to take good photos. No, they’re everywhere.

Is it harder for young photographers to kick off their careers nowadays?

Hell. It must be hell, because everything is available everywhere now. It fucks with your head and whether you want it or not, you are subconsciously copying the work of others. It must be very hard. I think it is much more difficult now to find your own voice. Everyone is a photographer now. But that doesn’t really matter. Quality will always be recognized. It’s actually good that photography is so accessible and that everyone can shoot. But the best will always rise.

As a photographer who has been shooting for a couple of decades already, have you ever been in a moral conflict with yourself while taking pictures of those people you were hanging out with?

I’m not there to moralize; I’m there to take pictures. Whatever it is, I will just shoot it. No problem. Actually not whatever it is… When I was younger, I would shoot anything, but now if I shoot someone and it makes him feel like shit, I am not gonna do that. It is like two people fighting: a photographer and a human being. And lately, the human being is winning, which is good.

Before my first book came out, I used to go after extreme situations, extreme content, gangs and drugs, etc. But I don’t do that anymore. In my Moscow book, for example, there’s nothing really shocking there. I no longer chase after extremes, but if they present themselves, I also don’t run away.

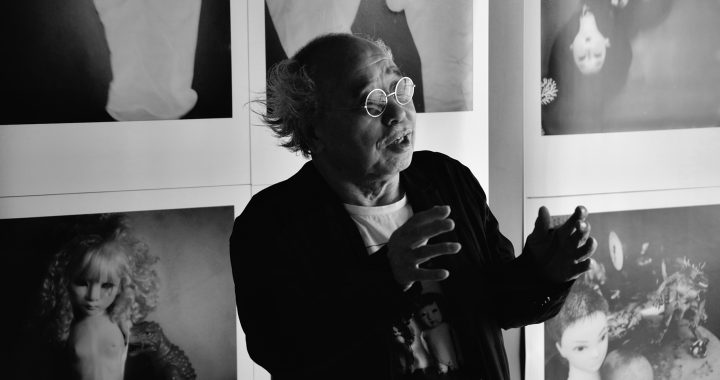

Boogie (Vladimir Milivojevich, *1969) was born and raised in Belgrade, Serbia, Boogie began photographing rebellion and unrest during the civil war that ravaged his country during the 1990s. Growing up in a war-torn country defined Boogie’s style and attraction to the darker side of human existence. He moved to New York City in 1998. He has published nine monographs, IT’S ALL GOOD (powerHouse Books, 2006), BOOGIE (powerHouse Books, 2007), SAO PAULO (Upper Playground, 2008), ISTANBUL (Upper Playground, 2008), BELGRADE BELONGS TO ME (powerHouse Books, 2009), A WAH DO DEM (DRAGO, 2016), IT’S ALL GOOD ANNIVERSARY EDITION (powerHouse Books, 2016), BELGRADE GUIDE (New Moment, 2017) and MOSCOW (powerhHouse Books, 2019). He has shot for high profiled clients and has been published in world renowned publications. His recent solo exhibitions include Paris, New York, Tokyo, Milan, Istanbul and Los Angeles. Boogie lives in Brooklyn and all over the world.